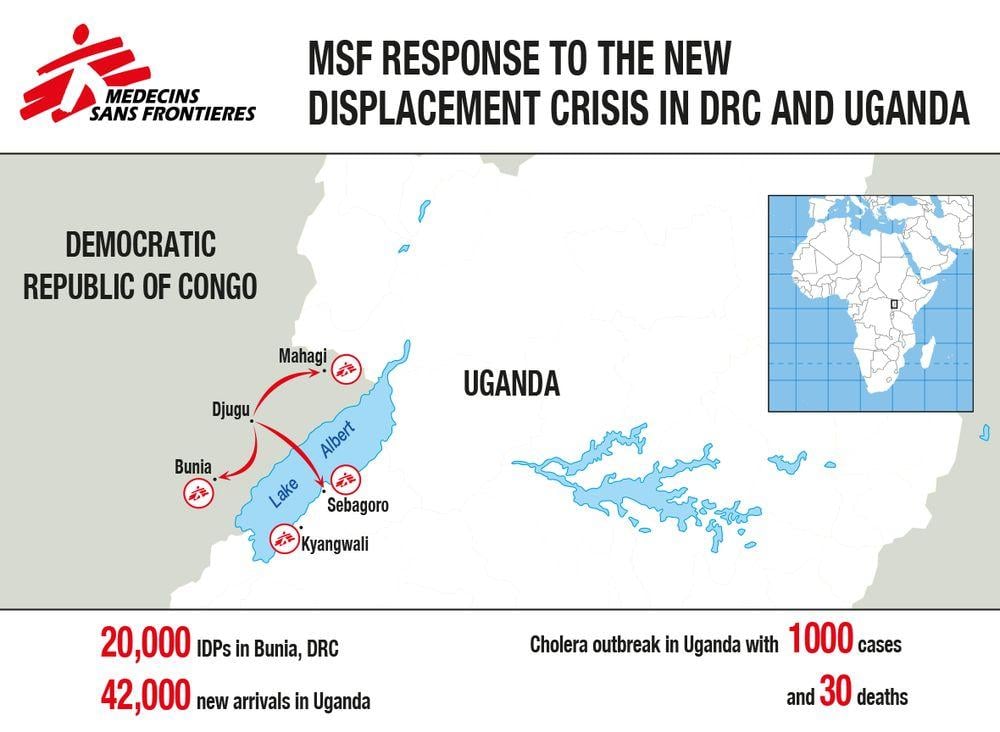

In December, violence between communities flared up in Ituri province in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). It grew in intensity in February and fighting broke out around the area of Djugu. Houses were burnt, people were killed and tens of thousands fled their homes in search of safety.

Some of the displaced made their way south to Bunia in DRC, whilst others travelled north to Mahagi. Many, however, remain in areas as yet inaccessible to aid organisations. In the last couple of weeks over 40,000 Congolese have paid to cross Lake Albert to reach safety in Uganda. It’s there where, on arrival, they have found dire living conditions, with the facilities in place to welcome them are overwhelmed by the number of people.

On 23 February, the health authorities in Uganda confirmed a cholera outbreak affecting the displaced and host communities in Hoima district, in the west of the country, where the new arrivals are hosted. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is working on both sides of the lake, offering medical humanitarian assistance to those in need.

What’s happening in Ituri Province (DRC)

In mid-February it was estimated by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) that around 20,000 people were sheltering in Bunia town. Most are living with friends and family, whilst around 2,000 are gathered at a temporary site at the regional hospital. MSF is supporting basic healthcare in three health centres in Bunia town, Bigo, Kindia and Lembabo, and is helping to refer severe cases to two nearby hospitals.

In the last two weeks, MSF teams have seen 2,117 outpatients, and of these 783 have been children aged under five, with 349 have been pregnant women. The main illnesses people are presenting with are malaria, respiratory infections and diarrhoea. Teams are also offering mental health consultations, as those arriving in Bunia are traumatised by the violence they have witnessed or been a victim of. There are unaccompanied children and people who have lost everything in their flight.

MSF has undertaken water and sanitation work at the hospital site, including installing a water supply and erecting 20 latrines and 10 showers. Teams have distributed 1,200 kits of non-food items such as blankets and soap, and continue to support the distribution of food such as flour, salt and rice to the displaced.

Most of the displaced people in Ituri are living with host families, but some are sheltering in schools, churches or small informal camps,” says Florent Uzzeni, emergency coordinator in DRC. “Many in Bunia are women and children who are totally reliant on aid for their most basic needs, such as food and water. We know that there are many displaced people in the areas we can’t yet reach due to insecurity, and every effort needs to be made to bring them the assistance they so desperately need.”

A team is also present in Mahagi, further north, where exploratory missions are ongoing. MSF has been providing remote support to the harder-to-reach areas such as Drodro, including through donations of drugs and equipment, and kits for treating the wounded. As very little help is able to reach these people, many are gradually making their way north in search of food, medical care and shelter.

Crossing the lake

A knock-on effect of this violence is that according to the UNHCR, since the beginning of January over 42,000 Congolese refugees have landed on Ugandan shores to escape the fighting, using overcrowded and rickety fishing boats and canoes to cross Lake Albert. The journey to reach Uganda can take between six to 10 hours, and there have been reports of refugees who drowned after their boat capsized.

“New arrivals tell us of attacks at night, and a small number have deep cuts and wounds. Many arrive traumatized and exhausted, with sick children,” explains Ahmad Mahat, emergency coordinator in Uganda. “Those using small canoes sometimes had to paddle for almost three days to reach safety here.”

What’s happening in Hoima district (Uganda)

Refugees disembark in Sebarogo, a small fishing village in Hoima district, equipped with a landing site. The site was soon stretched beyond its limit when, in mid-February, up to 3,000 people started landing each day during the height of the current refugee influx.

Numbers have now decreased, partly because of weather conditions and prohibitive prices, with only hundreds of new refugees now landing each day. New arrivals quickly leave Sebarogo for Kagoma reception centre which is managed by the authorities and UN partners, and they wait there for registration and humanitarian assistance before moving to a refugee camp, mainly Kyangwali (Maratatu) settlement, and other camps in mid-west Uganda.

However, bus transportation and the registration system were at times so overwhelmed in February that the refugees stayed at the landing site for several days and up to a week, with barely any assistance, no latrines, and no access to water except for the lake. Some moved on to Sebarogo town to join relatives and host families.

Kagoma reception centre and Marutatu settlement (part of Kyangwali) currently cannot cope with the influx of refugees. New arrivals already made vulnerable by their flight and the violence they experienced back in Ituri end up sleeping in the open air, exposed to the rains that have started, with inadequate access to water and food, in appalling hygiene and sanitation conditions. Health authorities recently confirmed a cholera outbreak in the region, with at least 1,000 severe cases that require hospitalisation, including more than 30 deaths since mid-February.

“The situation in Uganda is extremely alarming, with the trend in cholera cases still increasing and a very high mortality rate,” says Mahat. “In addition to dedicated cholera treatment centres, we are scaling up our response as quickly as possible, setting up a water treatment plant at Sebagoro landing site to increase access to clean water for the refugees as well as communities living along the shores, putting in place oral rehydration points, surveillance, water trucking and we are also building additional latrines.”

“However to control this deadly outbreak and protect those most at risk, it is really urgent to undertake a cholera vaccination campaign in the coming days. This must be a part of the routine response for such epidemics,” Mahat continues. “After discussing with global partners, a stock of vaccines has been made available for this emergency campaign and we stand ready to assist the Ministry of Health as soon as the green light is given.”

In Sebarogo, MSF teams have set up a 50-bed cholera treatment centre (CTC) in the town’s health centre, which they also support with additional supplies and resources, and are running a mobile health post at the landing site that allows for the most urgent cases to be referred to the health centre. MSF has also opened a 50-bed CTC in Kasonga health centre, which is near the reception centre. Patients are also referred here by other actors from Maratatu settlement, which currently hosts 23,000 people.

In Kagoma reception centre, 5,263 children have been vaccinated against polio and measles by MSF teams, and 2,160 women of childbearing age have been vaccinated against tetanus. MSF has opened a 24/7 outpatient clinic where over 2,000 patients have been treated since mid-February, most suffering from diarrhoea and cholera, malaria and respiratory infections. Antenatal care and assistance to victims of sexual violence are also provided at the clinic.

The situation in Ituri province remains unpredictable and a new wave of violence could cause a fresh influx of people to Uganda. At present, insecurity is preventing many of the displaced Congolese who remain in their country from accessing life-saving assistance. MSF is working to reach them. In Uganda, a deadly cholera outbreak and inadequate provision of humanitarian aid means that an acute emergency is now developing on the shores of Lake Albert.