Continuing violence, recurrent disease outbreaks, and ongoing displacement are all set against a backdrop of already limited access to basic services in South Sudan and now organisations that have been filling gaps are facing funding cuts by their donors. This is all while an estimated 820,000 people have crossed into South Sudan as of September 2024, searching for safety from the conflict in Sudan, whether as a returnee or refugee.

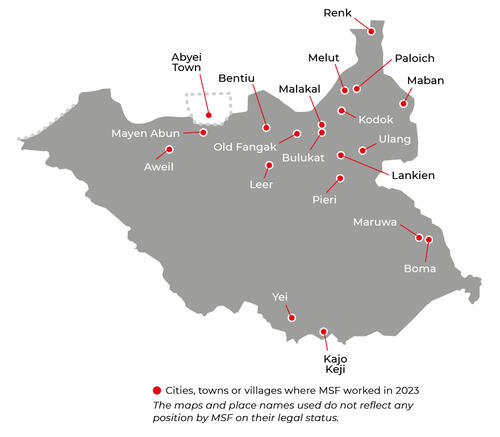

MSF teams are dedicated to providing a range of services in six of South Sudan’s 10 states, and in two administrative areas. Our services include basic healthcare, mental health support, vaccinations, disease outbreak response, and more.

What we're doing in South Sudan

Our teams are supporting in and providing vaccination campaigns for yellow fever, measles, and hepatitis E. In the first six months of 2024, our teams vaccinated over 10,000 children for measles. And after a hepatitis E outbreak was declared in Jonglei state, we launched a mass vaccination campaign with the Ministry of Health. This work continues, as we vaccinated people against hepatitis E in at least 111 villages in 2024. Since July 2024, MSF has also been rolling out the R21 malaria vaccine in two states in South Sudan.

Renewed violence in Abyei and Twic, as well as war-injured people crossing from Sudan, means our teams are seeing people requiring surgery. In Abyei and Twic we’re providing comprehensive care in four facilities and supporting with case management in camps for displaced people. Our team in Abyei performed surgery on 815 people who had violence-related injuries between January and June 2024. Access to specialised care remains limited, with no operating theatre available in Twic County.

Our teams are diagnosing and providing people with comprehensive care for. In Unity state, MSF has been providing specialised care for HIV since 1989. Many patients struggle to stick to their prescribed treatment regimen because of the significant side-effects. So, our team is supporting patients with post-test counselling and raising awareness through community meetings. In Central Equatoria state we are also testing pregnant women to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

In South Sudan, maternal mortality remains high at over 1,150 deaths per 100,000 live births, mainly due to infection, haemorrhage, and obstructed labour. In 2023, MSF restored the operating theatre of a hospital in Central Equatoria state that had been destroyed during the civil war. With this theatre, safe deliveries and caesarean sections can be performed. Between January and June 2024, we assisted in 175 births at the hospital, including 30 caesarean sections.

The MSF Academy for Healthcare offers targeted learning programmes for medical and paramedical staff in South Sudan, aiming at upskilling the local health workforce. MSF also provides scholarships to young students joining nursing and midwifery programmes. Understanding the transformative power of education for health workers, the MSF Academy for Healthcare is providing programmes in nursing, midwifery, and outpatient care in South Sudan. In June 2024, 21 health workers graduated in Lankien, Jonglei state, with clinical practice skills.

Our activities in 2023 in South Sudan

Data and information from the International Activity Report 2023.

3,773

3,773

107.9 M€

107.9M

1983

1983

879,100

879,1

327,100

327,1

74,300

74,3

65,800

65,8

14,100

14,1

10,300

10,3