On the night of December 5, violent fighting shook Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic (CAR). In the hours that followed the start of fighting, MSF teams went to the city’s Community Hospital to provide emergency assistance and treat hundreds of wounded patients. Sixteen medical staff divided up among the emergency, surgery and hospitalization departments. Sabine Roquefort, a doctor, is one of them. Back in Paris, she recounts the crisis.

What was the situation when you arrived in Bangui? What was your mission?

I arrived on November 15. Things were already very tense and there was a lot of shooting in the city.

I was MSF’s emergency services manager for the entire CAR. We had already decided that it would be a good idea to position a surgical team in one of the city’s hospitals. In a week, we had set it up at the Community Hospital, which is a centrally-located facility, close to our living quarters. That’s important in the event of security problems. We had already worked there in April and May, after the capital was taken by the ex-Seleka forces. The hospital staff knew us, which made it easier to organize things.

How did you start?

We had to begin with the logistics. Rain was coming into the operating rooms, the paint was flaking off and there were mushrooms growing in the ceiling. We started by restoring one of the operating rooms. The international deliveries of medicine and medical supplies arrived in a week. A surgical team – surgeon, nurse-anesthetist and surgical nurse – also arrived very quickly. On Saturday, November 30, we were ready for the wounded.

On December 2, Bouali, a camp of Fulani nomads located three hours from Bangui, was attacked. People said that self-defense groups (anti-Balakas) had attacked them. The wounded made their way through the bush and stopped a car along the main road to get to the hospital. A woman told us that her 6-month-old baby had been killed with a machete. She had lacerations to her scalp. One of her other children was wounded. We operated on him and several others. In fact, contrary to what we anticipated at the outset, this project also allowed us to treat victims of violence coming from outside of Bangui.

What can you tell us about December 5?

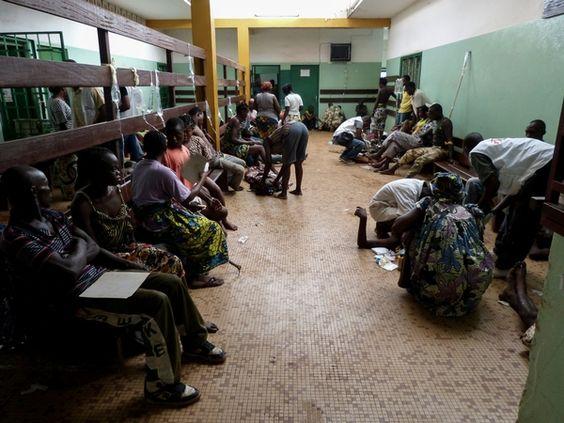

Fighting started around 5 a.m. in Bangui and intensified throughout the day. That day, we registered 120 people at the Community Hospital. Eight were dead on arrival. The wounded were treated primarily by MSF expatriates because security conditions prevented the Central African staff from getting to the hospital. Only the director managed to come. He operated at the same time as we did, with support from one of our nurse-anesthetists and using our supplies.

Some of the wounded patients required immediate treatment. Those included thoracic and abdominal wounds, for example, which take a lot of time because you have to do an exploratory laparotomy – open the belly and check to see if there is a bullet inside the patient. That can take three to four hours. Most of the cases were open fractures - bullets in joints or in bones. I treated an elderly women. She had been shot in each knee. That’s going to affect her for the rest of her life.

What was the atmosphere like in Bangui and in the hospital on December 5 and the following days?

Armed men were coming and going in the hospital. Things were very tense. There were threats and pressure. We couldn’t stay there after curfew (6 p.m.) because it was too dangerous. We were afraid that the patients would be killed at night. Fortunately, that didn’t happen and we managed to avoid the worst.

Outside, we heard shooting. The situation felt chaotic, which it was. You had to be very careful traveling through the city. It was dangerous. There were corpses in the streets. It felt as though the city had been emptied out – there was no one in the street. People had fled or were hiding at home.

On December 8, we received a new flood of wounded patients after fighting near the airport, which is further from the hospital. Small groups were brought by ambulance, which meant we could manage the arrivals more easily. Many people were lightly wounded, but the numbers were very large. It was total confusion and required a major triage effort. We had to ask each patient to bring only one family member so that we could organize treatment as efficiently as possible and so the doctors could work in relative calm. This constant inflow and mix was quite stressful - wounded people, armed men, family, staff.

Did the Central African staff come back?

Yes, gradually, over several days, they were able to return to work. However, you must remember that it’s extremely dangerous for them. They received direct threats. We can’t ask them to take unnecessary risks. They had to be surrounded by expatriates because our presence protects them, at least for now.

What is the health situation in Bangui today?

On December 5, the main Bangui hospital, Amitié Hospital, was attacked. We went there a few days later and it had been completely ransacked. There was no staff and no supplies. It hasn’t operated since.

The Community Hospital is the only facility for adults that is currently open. We started a project at the Castor Maternity Center for minor surgery, obstetrical care and Cesareans and we launched mobile clinics. But that’s not enough. The health system was already in trouble before the latest crises. Everything has to be started up again, especially because the needs are so much greater given what’s going on now. The populations are extremely vulnerable today. They need basic primary care, but secondary care as well. Where is a seriously ill person supposed to go to be hospitalized in Bangui today? As of now, apart from the Castor facility – which has limited capacity – there is no other maternity clinic in the city, for example. It can’t be the only referral facility for all pregnant women in Bangui.

Obtaining supplies also remains a major problem, particularly fuel, which we need for the hospital generators. There isn’t enough gas, which is a problem for our cars, the ambulances, and our ability to move around.

What affected you the most during your mission in Bangui?

We are used to working in very violent environments, but this organised, willful intent to mutilate, wound and kill shocked me. Here’s the story of one family. Twenty armed men stormed their house and looted everything. The son, around 30, sustained machete wounds to both arms. They fled toward the airport, a few kilometers from their home. They had to cross a river with water rising chest-high, and he – with a double open fracture - had to keep his arms raised. This level of violence and suffering is what struck me the most, compared to the other conflict settings where I have worked.

We met journalists who had been in Bossangoa on December 5 and they were very frightened. These are seasoned reporters, but they were distraught as they told us what they’d seen – men taken by force out into the countryside, for example.

Bangui is not the only city affected by extreme violence. The entire country is involved and it’s been going on for months. There will be a lot of work to do gathering statements from witnesses. Without catastrophising the situation and avoiding shorthand like “genocide” or “Christians vs. Muslims,” we have to be able to give a name to describe what is happening in the CAR today. And what is happening there is serious and tragic.”