Caused by a water-borne bacterial infection of the intestine, cholera is transmitted through contaminated food or water, or through contact with fecal matter or vomit from infected people. Cholera can cause severe diarrhoea and vomiting, and rapidly prove fatal, within hours, if not treated. But cholera is very simple to treat – rehydration is key. Most people respond well to oral rehydration salts, which are easy to administer. In more serious cases, intravenous fluids are required. Ultimately, no-one should die of cholera.

Quick facts about cholera

Outbreaks can rapidly spread in over-crowded communities and in dense living conditions, such as refugee camps and in slums, when there is inadequate access to clean water, waste collection, and proper toilets. People being displaced, destruction of infrastructure, or a lack of public services can mean cholera is a serious risk in the aftermath of a natural disaster or during a conflict. Both drought and flooding can increase the risk for cholera. Drought decreases the available amount of clean water, forcing people to use contaminated water. Flooding can spread the bacteria and contaminate water sources.

Cholera is relatively simple to treat in most cases, with people with mild to moderate forms usually able to recover through treatment with fluids and oral rehydration salts, which are easy to administer. People who are severely dehydrated may need intravenous fluids and hospitalisation. In these cases, they should be admitted to a Cholera Treatment Centre (CTC). Without treatment, the mortality rate can reach 50 per cent. With proper medical care, it's around 0.2 per cent.

Cholera occurs in areas with poor access to sanitation and unsafe drinking water - so providing people with clean drinking water and proper sanitation facilities is vital to preventing and curbing any outbreaks. Our water and sanitation teams provide people with sachets to purify water, truck clean water in, and install, fix and clean out sanitation facilities such as toilets in affected areas. Informing people about good hygiene practices such as washing hands, using clean toilets, and using only clean water to drink and wash food, can also curb outbreaks of the disease.

Vaccines against cholera are orally administered, which is practical for mass vaccination and does not require medical personnel. Of the two vaccines used for mass vaccination, one does not even need a cold chain. We know that one dose of a vaccine provides sufficient protection and can reduce or prevent transmission of the disease, but vaccination officially requires two doses. However, in October 2022, a WHO-hosted vaccination coordination group – of which MSF is a member – exceptionally approved one-dose strategy, given a shortage of cholera vaccines and the high number of outbreaks around the world.

A rapid response is vital to containing the spread of a cholera outbreak. Quickly putting in place health promotion activities - educating people about how to help to limit the spread - plus water and sanitation activities, establishing treatment centres and vaccinating in an emergency response can help limit how far an epidemic spreads and reduce the number of people who fall sick or die.

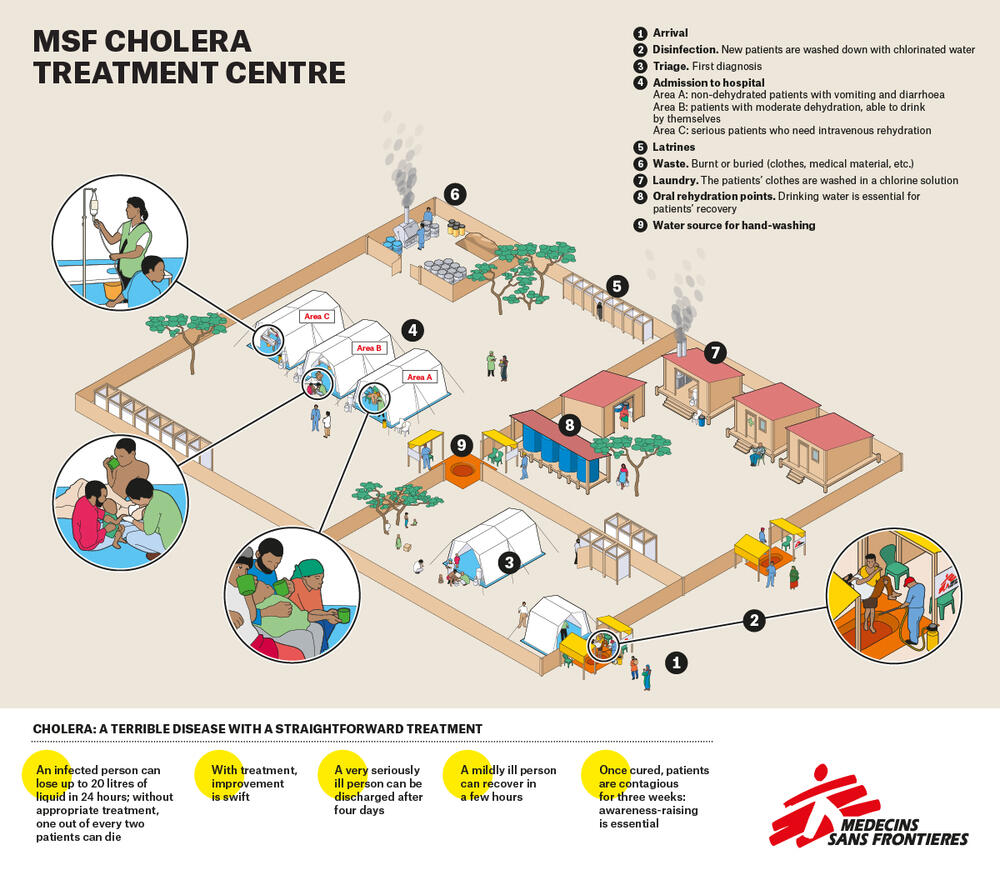

The design of the Cholera Treatment Centre (CTC) by MSF was a significant contribution to cholera epidemic response. A CTC is set up outside of the main hospital to prevent the spread of the disease and is fully autonomous. In open settings, with spread-out populations, treatment needs to be as close as possible to affected populations. Care can be decentralised to smaller-scale CTCs known as cholera treatment units and oral rehydration solution (ORS) points, supported by mobile teams.

Cholera outbreaks resurgence

A resurgence of cholera outbreaks

In 2023, 30 countries recorded cases of cholera. MSF teams responded to cholera outbreaks in more than 10 countries, including in Lebanon, Haiti, Syria and DRC; in many of these countries, the situation is worrying. But why are we seeing a resurgence of cholera outbreaks?

What happens in an MSF cholera treatment centre?

thinglink.comMSF often responds to outbreaks of cholera in the countries we work. But how do we set up our cholera treatment centres to ensure our patients get the best care possible - and that the disease doesn't spread? Learn more about the layout and activities of an MSF cholera treatment centre in this interactive guide.

Learn more about MSF's cholera treament centres

MSF responds to cholera outbreak in Liberia

Papua hit by simultaneous epidemics

Murky Waters: Why the cholera epidemic in Angola was a disaster waiting to happen

Access to safe and free water needs to be guaranteed

As the number of infected people reaches 20,000, response to Angola cholera epidemic remains insufficient

Cholera in Angola: With almost 500 new cases every day, MSF urges Government to take much stronger action

MSF responding to severe cholera outbreak in Juba

Cholera in Zambia: 'People do not want to talk about it. It's a dirty disease'

Cases still rising in cholera outbreak in Lusaka

Research & Analysis

An interactive guide to an MSF cholera treatment centre

Cholera Treatment Centre

What is a Cholera Treatment Centre? Médecins Sans Frontières provides information about the key parts of a CTC, and what patients can expect in their treatment.

Beyond cholera: Zimbabwe's worsening crisis

Murky Waters: Why the cholera epidemic in Angola was a disaster waiting to happen

MSF Field Research

We produce important research based on our field experience. So far, we have published articles in over 100 peer-reviewed journals. These articles have often changed clinical practice and have been used for humanitarian advocacy. All of these articles can be found on our dedicated Field Research website.

Visit site