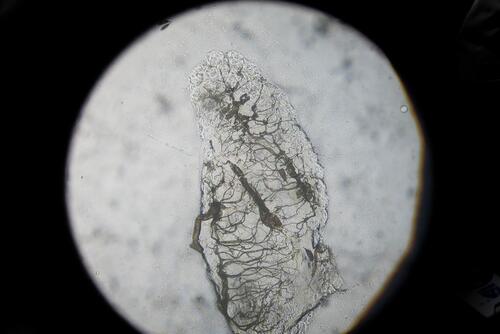

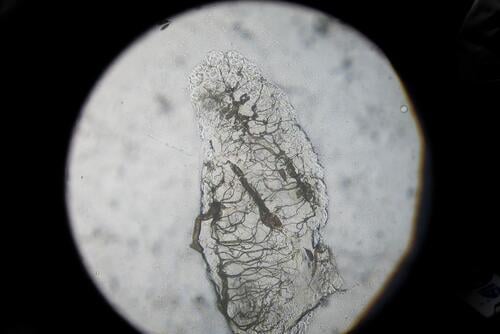

Biologist Melfran Herrera studies an Anopheles mosquito under a microscope. He carefully removes its ovaries to see whether or not it has laid eggs. If it has, it is an “old” mosquito that has already consumed blood, is probably infected and could become a transmitter of the dreaded disease malaria.

Melfran has more than 20 years of experience as a specialist in the control of insect-borne diseases. He works as a vector control supervisor with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the state of Sucre in northeastern Venezuela, where MSF supports the regional health authorities in the fight against the disease.

Malaria resurges with a vengeance

Malaria was almost under control in Venezuela in the 1960s but has made a major comeback in recent years. According to the World Health Organization, there were nearly 470,000 cases in 2019,<p>The Venezuelan government has not published malaria case numbers since 2016. WHO source numbers: <a href="https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015791">World Malaria Report 2020</a></p> which makes Venezuela one of the most affected countries in Latin America.

Sucre is one of the regions with the highest incidence of malaria in the country. Since 2019, MSF has worked in the communities of Yaguaraparo, Coicual, Putucual, Guaca, Caño Ajíes, Agua Clarita and San Vicente, where the disease prevalence is particularly high.

The local health authorities and MSF are focusing on three main activities: diagnosis and treatment, health promotion and vector control.

Preventing transmission through vector control

Vector control refers to preventing the transmission of diseases through the insects that carry them, the so-called vectors. It can be complex to carry out because, for the measures to be effective, teams need to know absolutely everything about these mosquitoes.

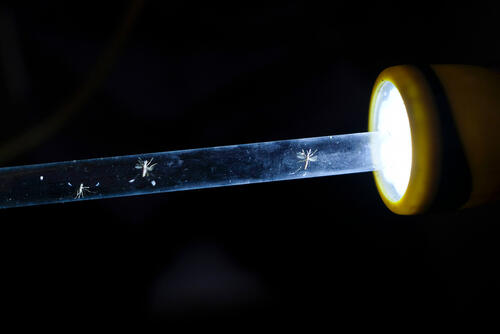

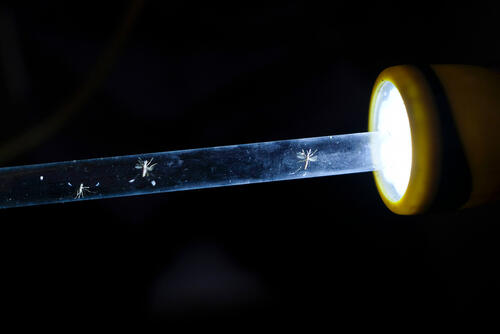

The first step is to locate possible breeding sites. The vector control team visit streams and lagoons near where malaria cases are found to collect water samples, and confirm the presence and density of Anopheles larvae. Next, the team go to local people’s homes to follow and trap mosquitoes with the intention of studying them.

The information they are looking for includes determining which species are present, their number, their average life span, the preferred time of day when they bite, and whether they enter houses and rest on walls.

Once they have all this information, the results are analysed to develop effective and sustainable vector control strategies. This might include treating ponds with biolarvicides,<p>A substance to kill the larvae of mosquitoes, but which is derived from natural organisms.</p> setting up schedules to spray the walls inside people’s houses, and distributing mosquito nets.

Measures lead to 80 per cent reduction of malaria

Medical teams at local health centres and the Maternity Hospital of Carúpano complement this work through the early detection and treatment of malaria, while health promotion teams reinforce messages related to care and prevention. The combination of all these measures has led to a significant reduction in cases of malaria.

The incidence of malaria cases has decreased by 80 per cent in areas where MSF teams have been working since 2019. In the first half of 2021, 1,641 malaria cases were reported in these areas compared to 8,566 cases in the same period in 2019.

Noble Garcia has brought her grandson to the clinic in San Vicente, a rural area of Sucre state, to be tested for malaria. The boy has symptoms of the disease, and not for the first time. In recent years, Noble has had the disease at least three times and her grandson has had it once. But she says that the situation has changed in the past year.

“You don't see so many people with malaria anymore,” says Noble. “We know how to take care of ourselves when we are sick and here we receive treatment.”

The MSF-supported outpatient clinic team has pricked the boy’s earlobe to determine whether he is infected. The result comes back positive. He is one of the 200 million malaria cases diagnosed worldwide each year, but fortunately the boy was diagnosed early. He will receive treatment and is likely to recover in just a few days.

MSF has been working in Venezuela since 2015 and works to reduce malaria in the states of Anzoátegui, Bolívar and Sucre. During the first half of 2021, MSF teams in these three regions carried out 80,631 malaria tests, diagnosed and treated 14,858 people for the disease, and distributed 23,000 mosquito nets to various communities. Currently, MSF has operations in Amazonas, Anzoátegui, Bolívar, Miranda, Sucre, Táchira and the Capital District.