The humanitarian context in northeast Nigeria

Nine years of conflict between the military and non-state armed groups have taken a heavy toll on the population, with serious humanitarian consequences. Thousands of people have been killed; others have been deprived of access to medical care and died of easily treatable disease such as malnutrition and malaria.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 1.9 million people are internally displaced in the northeastern states of Borno, Adamawa and Yobe, and 7.7 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance.<a href="https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/nigeriasituation#_ga=2.180696423.1358997199.1543419016-1271149834.1543419016">UNHCR data</a> More than 230,000 people have fled to the neighbouring countries of Niger, Chad and Cameroon.

The emergency is not over

In northeast Nigeria, services remain inadequate and there are many gaps in the humanitarian response. Security and access issues hamper the delivery of aid, and humanitarian organisations cannot provide assistance in all locations where it is needed.

Nevertheless, hundreds of thousands of people remain heavily dependent on aid for their survival. In some places, people have been stranded for nearly three years with little prospect of returning home due to the continuing conflict.

Immediate needs are not being adequately addressed

Much of the humanitarian aid is concentrated in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, which hosts one million internally displaced people, but services remain insufficient even there.

MSF recently scaled up its activities in the town to respond to a cholera outbreak which was declared by the Ministry of Health on 5 September 2018. MSF teams are also treating an increasing number of children suffering from severe acute malnutrition, malaria and lower respiratory tract infections.

Outside Maiduguri, the ongoing conflict restricts the movements of the population and of humanitarian organisations.

Civilians caught in a cycle of violence, fighting for survival with very little means

Most people live in towns or enclaves controlled by the military. Due to restrictions on their movements, most people are unable to farm, fish or sell their goods, leaving them dependent on humanitarian assistance.

In some locations, living conditions are catastrophic. Basic amenities are overstretched, water shortages are common, and sanitation is inadequate. Any disruption to the provision of assistance in these areas could have deadly implications.

Areas out of reach of assistance

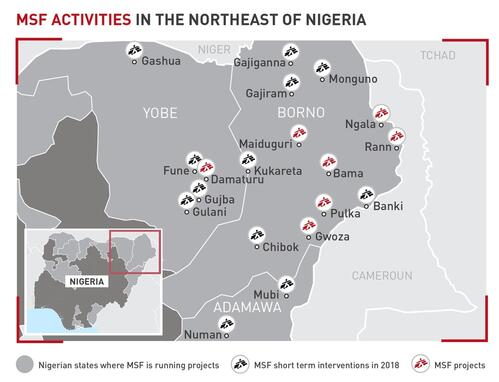

MSF is currently providing lifesaving medical care in permanent facilities in Gwoza, Pulka, Bama, and Ngala. Mobile teams are providing medical aid in Rann and Banki, and via mobile emergency clinics in Yobe and Adamawa.

Little is known about the needs of people living outside the enclaves. OCHA estimates that around 800,000 people live in areas that are inaccessible to humanitarian organisations. The only information that MSF has about these areas is from newly displaced people who continue to arrive – not always by choice – at towns controlled by the military.

The conflict is not over in northeast Nigeria and civilians are caught in the middle. MSF patients have reported harrowing stories of extreme violence perpetrated by all sides to the conflict.

MSF medical activities

Borno and Yobe states, January to October 2018

98,137

98,137

31,969

31,969

31,025

31,025

5,997

5,997

6,320

6,32

265,370

265,37

7,968

7,968

332,668

332,668

MSF activities in Borno state

Maiduguri, capital of Borno state

We run a 78-bed inpatient therapeutic feeding centre (ITFC) in Fori, in the south of the state capital, Maiduguri, and an outpatient feeding programme for severely malnourished children without medical complication and children with moderate acute malnutrition.

Between January and October 2018, more than 3,100 children were admitted to the programme, with a significant increase in patient numbers during the so-called hunger gap between July and September.

We also run an 80-bed paediatric hospital in Gwange for residents of Maiduguri and internally displaced people from across the region. This year, the malaria peak season saw a significant increase in admissions, and the team had to almost double the bed capacity, setting up extra tents in the hospital grounds and at times treating up to 70 patients in the intensive care unit.

Enclaves in Borno state

We run a 71-bed hospital providing a wide range scale of secondary health services to the local population and displaced people in Gwoza, 135 kilometres southeast of Maiduguri.

Displaced people from northeast Nigeria and neighbouring Cameroon often arrive in Gwoza, a town controlled by the military and surrounded by mountains and the Sambisa forest, where armed groups are believed to be active.

We carry out nutritional and health screenings of new arrivals and provides them with mental health support. Where necessary, our teams also carry out protection activities.

We also provide primary and secondary healthcare, and health screenings for new arrivals, in the town of Pulka, southeast of Maiduguri.

Pulka hosts more than 40,000 displaced people, some in camps, others living in the host community. The town is completely controlled by the military and people’s movements are limited.

As a result of the unplanned and large-scale movement of people returning from Cameroon, not always voluntarily, there have been severe shortages of food, water and shelter in Pulka, and some basic needs remain unmet.

The town of Ngala, near the border with Cameroon, has been under the control of the Nigerian military since February 2015. Approximately 50,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) live in Ngala IDP camp.

We provide primary and secondary healthcare for the displaced and local population in Ngala, and run a 66-bed inpatient facility whose services include: intensive care; emergency care; inpatient nutrition treatment; and maternity services, including assisted deliveries and neonatal care.

We were providing medical care in Rann in January 2017 when the town was bombed, killing 90 people and injuring 150 others. The Nigerian military later claimed responsibility for the bombing, saying it was a mistake. Three staff working for an organisation subcontracted by MSF were among the dead.

On 1 March 2018, an attack on the military base opposite the MSF compound killed a number of Nigerian Armed Forces and NGO workers who were living in the compound. Three female NGO staff were abducted: two have since been executed and one is still missing.

We provide outpatient consultations, run an outpatient therapeutic feeding centre and have opened a stabilisation unit for more severely ill patients who have no access to secondary healthcare in Rann. Our teams also support health promotion and water and sanitation activities.

In November 2018, we responded to a cholera outbreak in Rann, implementing preventive activities in the community to contain the outbreak and treating 55 patients in its cholera treatment unit.

The town of Bama is located 60 kilometres from Maiduguri. It hosts some 29,000 IDPs living in a camp, in addition to the resident community. We have been working intermittently in Bama since 2016. Our latest response started in August 2018 after an assessment revealed a critical humanitarian situation, with a lack of shelter and severe malnutrition among newly arrived displaced people.

There is no functional secondary healthcare facility in the town, where we are running a 40-bed paediatric hospital which includes an intensive therapeutic feeding centre.

MSF activities in Yobe state

Yobe is one of the poorest states in Nigeria. Although it is relatively stable, armed groups are known to be active in the north and south of the state. Healthcare facilities in Yobe are very basic and people have limited access to medical care and health facilities.

In Damaturu hospital, we operate a 25-bed emergency paediatric unit, a 12-bed isolation ward and a 50-bed inpatient therapeutic feeding centre for children under five with severe malnutrition and accompanying health complications. Our teams also provide care for victims of sexual and gender-based violence and run a mental health programme.

Cholera response – September to November 2018

The WHO and Borno Health Commissioner declared a cholera outbreak on 5 September 2018 in Borno state after weeks of denial. On 17 September, a cholera outbreak was also declared in Yobe state. MSF was one of the main organisations to respond in both states.

Until late October, MSF supported a number of cholera treatment centres, cholera treatment units and 24-hour oral rehydration points in Maiduguri, Ngala, Chibok, Bama, Damaturu, Gulani, Gudiba, Fune, Mubi and Maiha, treating close to 8,000 patients.

In early November 2018, the cholera outbreak spread from Gambaru/Ngala to the Cameroonian border town of Fotokol. MSF’s team in Ngala supported the installation of a 60-bed cholera treatment centre in Fotokol. Cholera cases were also reported in Rann, where MSF set up a 20-bed cholera treatment unit.

In November 2018, MSF supported an oral cholera vaccination campaign in Gambaru, Ngala, Gashue and Gulani, vaccinating 332,688 people against the disease.

Emergency response and seasonal activities

In January 2018, we established a Nigeria Medical Emergency Team (NIMERT) to support our emergency response, not only but in particular in the country’s north. The team has, among other things, supported an emergency measles vaccination in Yobe state and responded to a Lassa fever outbreak in Ondo state and a cholera outbreak in Bade, treating more than 400 patients in its cholera treatment centre and conducting a mass vaccination campaign targeting 125,000 people in the state’s most affected districts.

In 2017, MSF handed over its medical activities in Banki to Unicef but continued to support the displaced and local population of this town with seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) activities. SMC was also provided through regular projects in Maiduguri, Rann, Monguno, Gajiganna and Ngala. MSF distributed a total of 259,651 malaria prevention doses in 2018.