In response to high levels of sexual violence in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo's Ituri region, MSF has launched a project in Mambasa to provide the survivors with medical and psychological care and treatment for sexually transmitted infections.

Driving along the red mud road, the MSF Land Cruiser passes through a cloud of white, yellow and orange butterflies. On either side of the road is thick forest. The trees are packed together so closely that visibility is limited to a couple of feet.

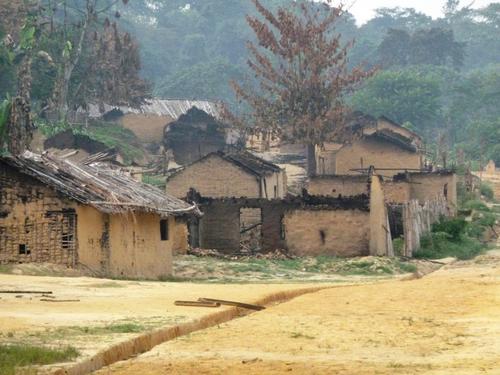

We are not far from the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. Amongst the trees are animals on the brink of extinction, as well as elephants and the villages of pygmies, the original inhabitants of this region. The trees also hide gold and diamond mines, both official and unofficial, smugglers of hardwood, poachers, armed men from Mai-Mai militias, and a whole series of other men carrying weapons.

The MSF staff in the vehicle are one of three medical teams, in a project launched in February 2016, who circulate between the towns of Mambasa, Nia-Nia, Bella and PK51, stopping in each village along the way to provide care for victims of sexual violence and people suffering from sexual transmitted diseases.

“In March alone, our teams took care of 123 victims of sexual violence and treated 907 people for sexually transmitted diseases” says Mame Anna Sane, MSF medical team leader. “These are very big numbers. That is almost four people raped per day – and that is just the ones coming to health facilities. Rape is so taboo that many people don’t come for help, so the real numbers are likely to be much higher.”

Each of the three MSF teams is made up of a nurse, a psychologist and a health promoter, who provide support to nine health facilities in the region by training the local staff in how to provide medical and psychological care for survivors of sexual violence. The MSF teams also provide supplies of the necessary medicines, and work with local communities to raise awareness about sexual violence and encourage victims to seek medical care promptly. Rape survivors need to come for help within 72 hours of an assault for the treatment to be effective. MSF teams also educate people about the symptoms of sexually transmitted infections so that people recognise them and come for treatment.

Taking care of the survivors

The work with local communities is having results, and there is evidence that rape survivors are coming forward more promptly for treatment. While we are at Biakato health centre, a 70-year-old woman who survived a violent gang rape is brought in by a group of relatives and neighbours. Two days earlier, she was asleep at home when three armed men broke down her door. They dragged her out of the house and into the forest, where they beat her and then raped her one by one. They left her in the forest, naked and unconscious. At the health centre, she will receive treatment for HIV and other sexual transmitted diseases, and psychological support. Her daughter is with her – but not all patients have family members to support them.

Marie, aged 37 years, is in the maternity ward at Biakato health centre. She has just given birth to a boy and she is alone. As she went to sell drinks in a mine near her home, Marie was kidnapped by a Mai-Mai group. They kept her prisoner for more than a year and raped her repeatedly. Finally she managed to escape when the Congolese army attacked the camp where she was being held. She returned to her husband, but he rejected her because she was four months pregnant from one of the rapes she had been subjected to.

A medical emergency

“Our work involves changing mentalities to get rid of the taboo around sexual violence, and to be able to offer proper care to every victim – the mentality of the local population, but also of the authorities,” says Mame Anna Sane. “Of course there is a criminal and legal aspect to sexual violence, but for us it’s first of all a medical emergency.”

MSF’s project in Mambasa is set to last six months initially, after which it will be reassessed. But one thing we know is that people’s need for medical and psychological care in response to sexual violence in the Ituri region is already far above what we expected.