Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has begun medical activities in Bikenge, an isolated mining town in Maniema Province, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). For the first few months, as they bring in supplies, the MSF teams are offering free healthcare to pregnant women, children under 15, surgical emergencies and victims of sexual violence. Once the necessary supplies have arrived, free health services will be extended to all. Since activities began on 23 March 2015, the team has carried out more than 2,150 consultations, 21 emergency surgeries and assisted at nearly 100 births.

Bikenge is located deep in the forests of Maniema Province, where some of Congo’s worst health indicators are found. The roads linking it to other towns are extremely poor and many parts are impassable by car for most of the year; getting to it requires one day of driving from the provincial capital, Kindu. Its remote location, as well as the lack of international organisations and functioning state-run health centres in the region, means that access to quality healthcare is more or less impossible for most people.

Artisanal mining activities aggravate the already poor health situation in the area. Such activities pollute local water sources, create mosquito-infested pools of stagnant water, and create dust that can cause respiratory infections. Many people come from other parts of the province to make their living in the mines surrounding the town. The resultant overcrowding also makes for worrying health indicators like high levels of sexual violence and infections linked to unsanitary living conditions.

“MSF’s presence in the health centre in Bikenge will help thousands of people get the quality health care they need, but otherwise couldn’t access,” says Michele Telaro, project coordinator of the new facility. “Here we’re right in the middle of a healthcare desert – for tens of kilometres in any direction, there’s very little in terms of quality medical services.”

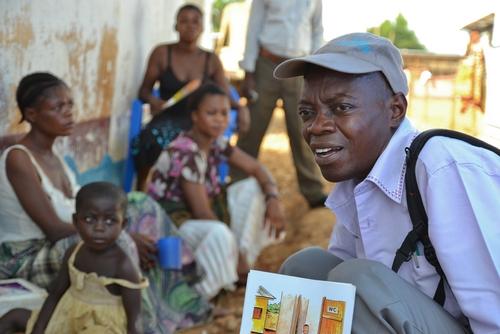

Due to the extremely remote location of the project and the lack of international actors present in the area, the MSF team has had to work hard to dispel myths and misperceptions about the organisation’s work. Now that activities have begun, the community’s perception and understanding of the MSF teams has improved. But more remains to be done.

“When a new MSF project opens, a huge amount of work goes into meeting local people, explaining who we are and why we’re here, and how we can help them,” says Michele. “There is so little in the way of humanitarian aid in this region that what we’re doing is totally new for local people. As a result, we have to work twice as hard to gain their trust.”

The 42-bed health centre is jointly run with the Ministry of Health. MSF has set up new temporary structures including an emergency room, a paediatrics ward, a post-operative care ward, a maternity ward and operating theatre, as well as a triage area, a pharmacy, a lab and four consultation rooms. In late 2015 and early 2016 a new health centre, better adapted to the needs of the population, will be built. The organisation is also rehabilitating a local water source for use at the health centre and by the local population.

MSF has been present in DRC since 1981, providing free, impartial medical care to people across the country. In 2014, the organisation’s Congo Emergency Pool (PUC) launched an emergency response in Kama and Kasese, Maniema Province, following a massive influx of displaced people from South Kivu.