The rainy season arrived several weeks ago in West and Central Africa, bringing with it seasonal diseases. Cases of cholera have already been identified in northern Cameroon, where Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is carefully monitoring the situation.

A team of epidemiologists in Dakar is supporting MSF in response to this latest outbreak and other regional epidemics.

Epidemiologist Franck Ale explains the challenges of their work.

What is the epidemiological situation of cholera in the region today?

We have observed cases of cholera in Cameroon since the beginning of March 2019. These cases are most likely linked to the last epidemic that spread across the country in 2018 – the end of which was never officially declared.

With the first rains in the beginning of May, we noticed a strong increase of cases with a high mortality.

The Ministry of Health has begun responding, and MSF teams on the ground are also on alert – supporting the response of local health authorities in Garoua city and in the nearby health district of Pitoa, where we intervened last year, as well as in the health district of Kaélé (in the North and Far North regions of Cameroon).

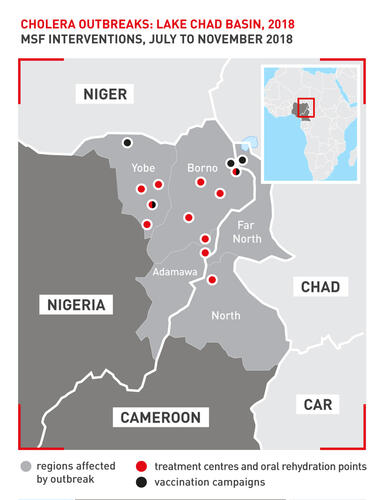

The outbreak is officially declared in Cameroon, as well as in the state of Adamawa, in northeast Nigeria. However, we remain highly vigilant in neighbouring regions, especially in Borno state, in northeast Nigeria, and in Chad.

Conflicts in the region continue to cause the movement of populations and weaken sanitation systems and hygiene conditions – conditions under which cholera can easily spreadFranck Ale, epidemiologist

Can you tell us more about last year’s cholera epidemics in the same area?

In countries like Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon, cholera is endemic and regularly occurs during the rainy season.

The Lake Chad region, which intersects all three countries, is an especially ideal environment for cholera: there have been regular epidemics in the area since 1971.

Investments have been made to address these outbreaks, ranging from cross-border collaboration, to strengthening surveillance in the surrounding countries and building response capacities involving public health actors of different specialties.

But conflicts in the region continue to cause the movement of populations and weaken sanitation systems and hygiene conditions. Unfortunately, these are conditions under which cholera can easily spread.

Last year, Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon reported many cholera cases. The first cases were observed in northern Nigeria and were linked to the conflicts and movement of the population in this area.

Movement of people within and between countries can easily cause an epidemic to spread. In Cameroon, there were even suspected cases detected in the capital, Yaoundé.

Today, we have the medical and public health arsenal to stop such an outbreak in a secure area, where communication and community health promotion resources are available.

However, it is more complicated when there is a combination of aggravating factors, like population displacements, weakened sanitation systems, and low access to water in particular.

Ways must then be found to quickly identify outbreaks and negotiate access, despite the security conditions, to respond quickly.

Last year, by monitoring what was happening in Nigeria, we were able to warn MSF teams in Cameroon of the arrival of the first cases in an area of the northFranck Ale, epidemiologist

How can we improve our response to epidemics?

West and Central Africa alone accounts for 30 to 40 per cent of the world’s cholera burden, according to the Regional Cholera Platform for West and Central Africa.

Organisations working in this region should make every effort to improve the detection and fast confirmation of cholera outbreaks, to respond more efficiently – especially in conflict areas.

In conflict contexts, preventive vaccination is essential in the areas surrounding an outbreak zone, for both internally displaced people and host populations, to limit the risk of the disease spreading.

For this to be possible, however, an emergency preparedness plan is needed – in which, for example, there is the possibility to pre-negotiate access to the vaccine and make it available in the area.

It is also essential to maintain a high level of epidemiological vigilance, in order to quickly identify new outbreaks of disease.

Vaccination is a very effective way to stop cholera epidemics, but it can only be done if the areas at risk are quickly identified.

Rapid laboratory confirmation of these cases is also a big challenge, especially in areas where insecurity and lack of laboratories make it more complicated.

Access to rapid screening tests is essential, as these tests allow fast identification of cases. This is necessary to formally declare an outbreak and to allocate the necessary resources to respond to it.

In conflict contexts, preventive vaccination is essential in the areas surrounding an outbreak zone, for both internally displaced people and host populations, to limit the risk of the disease spreadingFranck Ale, epidemiologist

What role does epidemiology play in an epidemic like this?

Epidemiological investigation can identify the causes of an epidemic and guide strategic responses.

The two key tools are surveillance – which makes it possible to quickly identify the first cases and to follow the geographical evolution of cases – and investigation, which involves investigating how each patient contracted the disease, to identify the people and places most at risk (such as contaminated water sources) and to organise targeted responses. These responses could include vaccination, as well as health promotion and water and sanitation activities.

Part of this work is done by epidemiologists in the field, in collaboration with the health authorities.

Our team contributes a regional perspective and can follow the evolution of epidemics across borders, sometimes where MSF has no ongoing activity. This is based on data made available by states or other actors on the ground.

Last year, by monitoring what was happening in Nigeria, we were able to warn MSF teams in Cameroon of the arrival of the first cases in an area of North Cameroon, where MSF has no regular activity. This enabled us to respond quickly.

From Dakar, we can also exchange information on cholera with the Regional Cholera Platform for West and Central Africa, and therefore contribute to a faster global response.

It is important that the independent voice of MSF be included in the discussions so that realities on the ground are taken into account.

In 2018, several cholera outbreaks were declared in West and Central Africa. Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria were particularly affected, with more than 45,000 cases and more than 900 deaths registered.

Cholera is indeed endemic to this region, especially to the Lake Chad Basin, where poverty and displacement of people due to insecurity worsen the situation.

MSF supported the local health authorities in the treatment of 10,500 patients and the preventive vaccination of more than 550,000 people in the three most affected countries: Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria.

From Dakar, teams carry out epidemiological surveillance on endemic diseases such as cholera, measles and meningitis on an ongoing basis, to support the work of teams in the field.