Stefanie, a midwife at Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) and Abdoulaye* from Gambia met twice within a few months in extraordinary circumstances: first on a search and rescue boat in the Mediterranean, then in quarantine for coronavirus in eastern Germany. This is the story of their reunion.

In distress at sea off Libya

Abdoulaye almost did not survive the day when he met Stefanie for the first time. It was the morning of 17 September 2019 and he was with 60 other people crowded onto a blue rubber dinghy off the Libyan coast. After nine hours at sea, the dinghy was beginning to take on water.

“The situation was getting bad,” remembers Abdoulaye, a tall young man from Gambia. “All our clothes were soaked with water. Everybody was frustrated. We were crying, shouting. We saw three ships, but they didn’t stop and they sailed away from us. No help!”

“When we saw Ocean Viking, we couldn't believe it,” says Abdoulaye. “When their speedboat arrived, they told us: ‘Turn off the engine! Sit down!’ But we couldn’t control our joy. They told us: ‘Calm down, calm down!’ But we couldn’t.”

When we saw Ocean Viking, we couldn't believe it... we couldn’t control our joy.Abdoulaye*, from Gambia, recounting his rescue from the Mediterranean

Stefanie, the then-medical team leader on board the search and rescue ship Ocean VikingMSF partnered with SOS MEDITERRANEE to run the search and rescue ship Ocean Viking, starting in July 2019. <a href="/eu-states-use-covid-19-shirk-search-and-rescue-obligations">In April 2020, we decided to end our partnership and our search and rescue activities.</a>, welcomed the rescued people on board. She remembers people’s relief when they realised that they had finally escaped the conflict in Libya and the exploitation and mistreatment they had endured there.

It was the third rescue operation by the crew of Ocean Viking that week, with another one soon to follow. It would take eight more days for the search and rescue ship to be allowed to dock in the Sicilian port of Messina, in Italy. During this time, Abdoulaye and Stefanie saw each other on deck every day.

“He always offered his help – picking up litter, handing out food or translating,” remembers Stefanie. “He was always a calming influence among the rescued people. Once, when there was some unrest, he stood up tall and said: ‘Hey guys, listen, the crew has something to tell us!’ He was trying to calm people down in a very nice way.”

Coronavirus quarantine in Germany

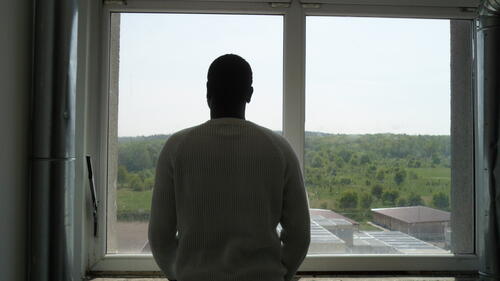

Seven months later, in the middle of the COVID-19 crisis, Stefanie is back on assignment with MSF, this time in Germany. In the town of Halberstadt, the primary reception centre of Saxony-Anhalt state, in the country’s northeast, is under quarantine. Dozens of asylum seekers staying at the reception centre have tested positive for the new coronavirus.

The centre’s residents are in a state of anxiety and fear, and have organised protests. Stefanie is one of a four-member team from MSF sent in to support the authorities by providing the centre’s residents with health education and psychological care.

“The first day, I was walking down the corridor with a colleague,” says Stefanie. “I saw a group of men, with one man towering over all the others by a head. We asked them about coronavirus and immediately a discussion started up.”

“The tall man kept on looking over at me, and I thought to myself: ‘Actually, I know him! Is it possible?’,” says Stefanie. “When all of their questions had been answered, he came to stand next to me and I said: ‘Hey, we know each other!’ And he just replied: ‘Ocean Viking, right?’.”

At this time, Germany was one of the hotspots of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, along with Italy, Spain and France. A lockdown was in force countrywide, with care homes and hospitals subject to particularly strict rules. Other people at high risk included asylum seekers in accommodation facilities, for whom it was difficult to protect themselves against infection by fellow residents.

At the primary reception centre in Halberstadt, more than 100 of the 800 residents were known to be infected. Those who tested positive were isolated in other facilities; elderly or sick residents, deemed at particular risk, were also able to leave the centre.

About 500 asylum seekers remained in the centre and were put under quarantine. Every two days, public health authorities carried out COVID-19 tests, and more and more people tested positive. To help deal with this difficult situation, the authorities of Saxony-Anhalt agreed for MSF, among other organisations, to launch a three-week response.

Lack of understanding and fear

“The biggest problem was that many people didn’t understand what coronavirus was all about,” says Stefanie. “There was a lack of information in their respective languages and too few possibilities to ask questions and have everything explained again in a comprehensible way.”

“Some had picked up wild theories from the internet or hearsay. As a result, some didn’t understand or follow the hygiene guidelines – they didn’t put on face masks, they didn’t keep their distance,” says Stefanie. “At the other extreme were residents who were so afraid of getting infected that they didn’t even dare open the door of their rooms – they were convinced they’d die.”

“There were these two extremes: lack of understanding and fear,” she says.

“In the beginning, I was very scared,” says Abdoulaye. “Six of my close friends tested positive. We had done everything together, but now they took them to another city. At that time, we heard that if you drink hot water with lemon, you will not be infected. So I drank a lot of hot water with lemon.”

Abdoulaye’s attitude changed as the quarantine went on.

“Later, I had some doubts whether coronavirus really existed in this camp, after all I read in the news outlets about the symptoms,” he says. “But then I had a conversation with Stefanie and her colleagues. They explained everything to me, and I said: ‘Wow, this is really dangerous!’.”

“The children danced along”

Abdoulaye and seven other residents were quick to agree to put on a show for other residents in the centre to demonstrate the most important rules about how to behave. It was performed as a dance-drama set to music: wash your hands, keep your distance, sneeze into the crook of your elbow, wear masks properly etc. They performed the show during food distributions.

“The men involved really enjoyed it,” says Stefanie. “The single men in particular couldn’t do anything during the quarantine: they couldn't go outside, the communal rooms were closed, they couldn't meet their friends and they had only limited access to the internet. They couldn't even cook for themselves.”

“Also, the other residents liked the dance. The children were totally enthusiastic – they stood two metres away from each other and danced along,” says Stefanie. “They also brought their face masks and put them on. The African women, especially, thought it was great to have some music playing. Even the office staff all opened their windows and watched the show.”

People understood, even if we didn't speak the same language. After our performance, people wore a mask frequently.Abdoulaye, rescued asylum seeker now in Germany

“Things improved”

After three weeks working in the reception centre, and after numerous discussions with residents and staff, the MSF team left behind concrete proposals for better communications, improved hygiene management and for expanding psychological care for certain groups of people.

In Abdoulaye’s view, the residents’ understanding of coronavirus has improved considerably.

“People understood, even if we didn’t speak the same language. After our performance, people wore a mask frequently,” says Abdoulaye. “Now, there is a distance of 1.5 metres in the food line. Things improved.”

Soon after, the residents finally regained their freedom of movement.

“The quarantine was lifted on a Sunday at midnight,” says Abdoulaye. “When they opened the gate, we just went two metres out of the camp and then came back again. We were so excited about it!”

“For one month, we couldn´t go out. We are all free now,” Abdoulaye says. “Of course, we have to wear a face mask and keep a distance and all this. The first thing I did the next day was go shopping to buy clothes and food: rice, chicken and some spices.”

*Name has been changed to protect privacy

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, MSF has shared our expertise in managing infectious diseases and provided medical, logistical and epidemiological support to various organisations in Germany, with a focus on particularly vulnerable groups such as the elderly, the sick, the homeless and refugees.