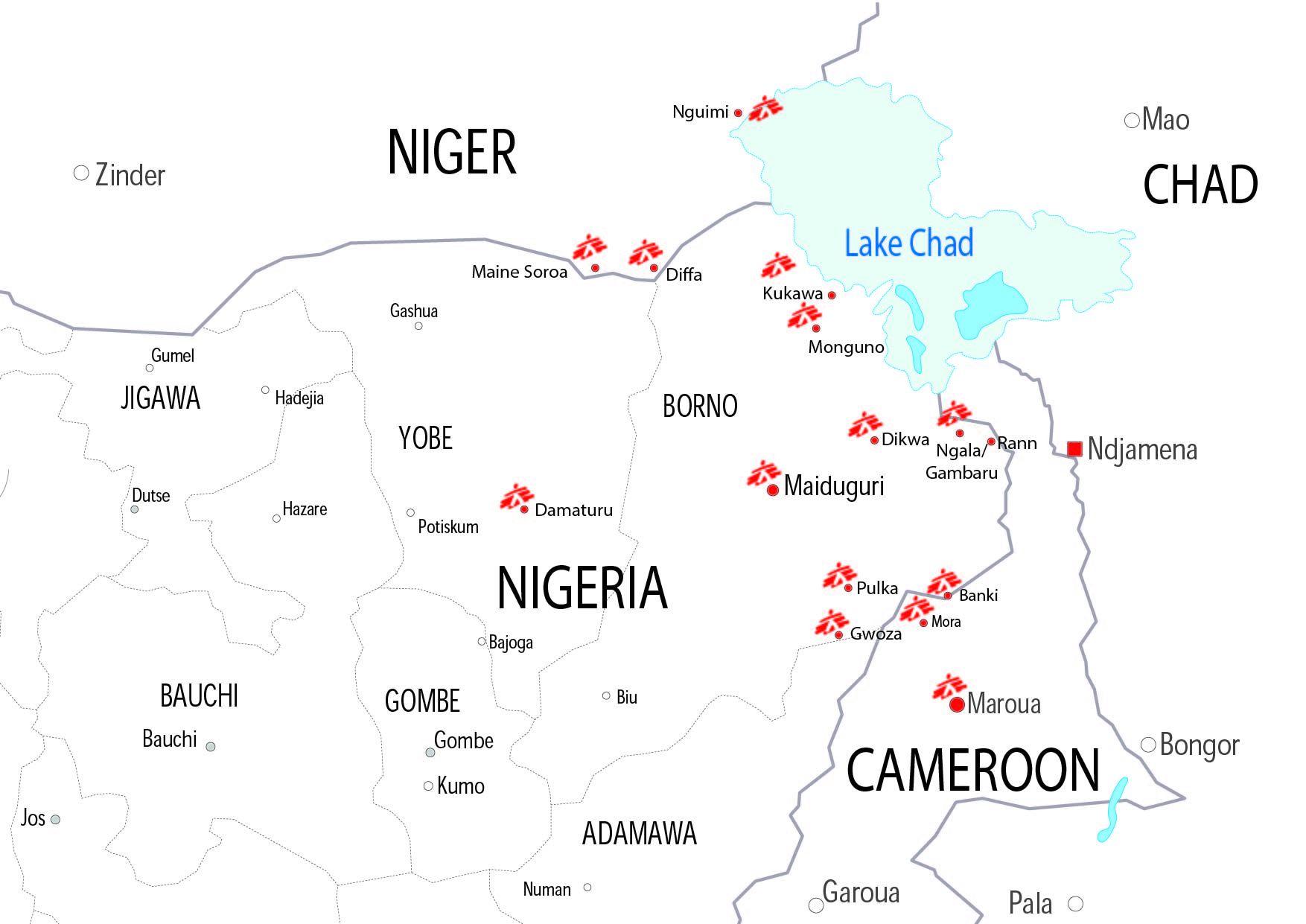

Around 17 million people live in areas affected by the violent conflict between non-state armed groups and military forces in the Lake Chad region, which has spread across Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria. More than 2.3 million people have been forced from their homes and remain displaced today.

The conflict has had a particularly damaging effect on the mental health of displaced people and those still living amid the violence.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has seen an increasing need for mental health support since the start of the conflict. Even in places where violence may have decreased, the consequences of displacement, hopelessness and despair continue to affect people’s lives and can lead to chronic mental health problems.

An important part of MSF’s activities in the region is aimed at reducing the psychological suffering of people caught in the Lake Chad conflict. Many are in need of psychological support having experienced violence, witnessed atrocities, or lost family members and belongings, whether as displaced people, as refugees or in their local communities.

Nigeria has borne the brunt of the Lake Chad conflict. Almost 8 million people living in northeastern Nigeria are heavily dependent on aid for their survival, including 1.6 million people who have been displaced from their homes.

In Pulka and Gwoza towns, where MSF primarily operates in transit camps, our teams offer psychological first aid to new arrivals. Our patients are mostly women whose husbands are often missing. These women have no choice but to leave their homes with their children, seeking security and humanitarian aid; their husbands have been killed, are suspected of belonging to armed groups, or are indeed fighting with these groups. We are also treating an increasing number of children and adolescents, for whom mental healthcare is particularly important to avoid future psychological complications.

Individuals facing exile lose every physical, social and material landmark.Yacouba Harouna, MSF psychologist working in Diffa

In Diffa, across the border in Niger, MSF has provided mental healthcare since July 2015. There, our team shares similar concerns. Due to the surrounding conflict and difficult living conditions, people live in a constant state of insecurity and distress. We see many patients with symptoms of depression, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder. Adults may feel guilt or low self-esteem and become isolated. Children may show regressive behaviour, while adolescents adopt at-risk behaviours, such as drug and alcohol abuse.

“Being forced to leave and settle in a new environment without knowing how long for is very destabilising. Individuals facing exile lose every physical, social and material landmark. They need to rebuild their lives from scratch and learn everything again,” explains Yacouba Harouna, a Nigerian MSF psychologist working in Diffa.

Achieving that is hard work, for which people may need psychosocial support.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Many former fishermen or herdsmen from the Lake Chad islands came to Diffa. They were used to being among economic leaders, with social and political influence. But having been displaced, they struggle to find ways to cope, learning how to earn a living through small business, or asking their children to work to prevent the family from going unfed.

“While people are moving, they also start to find appropriate coping mechanisms to regain routine, and a sense of control in their lives,” says Ana-Maria Tijerino, MSF psychologist referent in Geneva. “Not perfect or the same as before, but this is the resilience we are looking for in many of these communities.”

In Diffa, MSF teams have adopted a community-based approach to better identify and address the mental health needs of those they support, in particular with young people. Mental health outreach workers regularly visit community spaces, such as camps for internally displaced people, water points and schools, to seek out children and adolescents in need of care. Depending on their age and mental health concerns, patients are then referred to psycho-stimulation classes (drawing, dancing, story-telling, etc), family consultation or talking group sessions. Community outreach workers also organise education sessions for parents, other educators and community leaders to strengthen their ability to identify warning signs in young people.

In northern Cameroon, MSF provides mental healthcare for patients recovering from injuries, and also those with children suffering from malnutrition. While it is not certain that children are more likely to be malnourished if their caretakers (usually their mothers) are dealing with a mental illness, once such mental health needs have been addressed, improvements in the child’s health are seen more quickly. Our mental health teams work to reinforce the bonds between caretaker and child, encouraging psycho-stimulation sessions to tackle the developmental consequences of malnutrition. Caretakers are also offered a safe space to discuss their worries and symptoms, as many of them have been victims of the conflict as well.

In Mora, northern Cameroon, MSF psychologists have heard many women talk about the fear they feel. They fear sleeping inside, after having spent many nights sleeping in the bush with their children, hiding from nightly attacks, and turning on the lights during the night, after spending nights without making any noise or movement. The kind of support these women are now receiving can have a direct impact on the relationships they build with their children.

MSF has worked in the Lake Chad region since the beginning of the conflict in Nigeria in 2009, moving to other locations in neighbouring countries when the conflict spread in 2014.

In 2017, MSF ran around 25 projects in the Lake Chad region, with more than 150 international staff and more than 2,000 national staff, including doctors, nurses, psychologists and counsellors.

The teams carried out 400,000 outpatient consultations in northeastern Nigeria, 300,000 in Niger’s Diffa area, and 82,000 in northern Cameroon. Yet many people remain in insecure, temporary spaces, like the camps in Nigeria, where they are unable to move or adopt coping mechanisms, or in areas that MSF cannot access due to security issues.