Ten years ago, on 23 March 2014, Guinea declared an outbreak of Ebola. Beforehand, Ebola outbreaks were known to be dangerous, but small. Not this time, though: it would take two years and more than 11,000 deaths, before the epidemic was over. Dr Michel Van Herp, a renown Ebola expert even before 2014, looks back at the biggest Ebola outbreak ever, and answers five key questions.

1. What happened 10 years ago?

“When we read the reports of people dying of an unknown disease in Guinea, early in 2014, we thought this was probably an outbreak of Ebola, even if that disease was extremely rare in West Africa. We sent our Ebola teams on the ground.

At that time, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was one of the very few organisations with experience in Ebola outbreaks. But it became clear that this outbreak had been slumbering for months and was already present in more places than anybody was used to dealing with.

The outbreak happened in a place in the world where no one expected Ebola, in an area that didn’t interest the authorities, and no one was ready to deal with it. It took governments, UN agencies and aid organisations a very, very long time to take the outbreak seriously. MSF frantically rang the alarm bell, multiple times, but nobody seemed to listen.”

2. Why was this outbreak different?

“Never had Ebola outbreaks happened in so many countries at the same time. The virus spread in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, but there were also cases in Senegal, Mali and Nigeria. It was also the first time that Western countries, like Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US., had cases of Ebola.

The scale of this epidemic was absolutely unheard of. When it was finally over, in March 2016, more than 28,000 people had been reported to be infected, of whom 11,000 died. Before this epidemic, the largest Ebola outbreak had infected 425 people. Everybody, including our staff, was completely overwhelmed by this outbreak.”

Never had Ebola outbreaks happened in so many countries at the same time... The scale of this epidemic was absolutely unheard of.Dr Michel Van Herp, medical doctor and epidemiologist

3. Was the response to the outbreak different, too?

“For almost six months, the world tried to ignore this outbreak. Only by the end of the summer of 2014, did governments and aid organisations finally start to help.

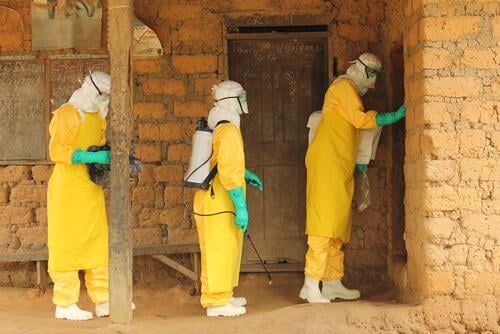

At the time, there were no treatments for Ebola. Patients would be admitted in an Ebola clinic, mainly to avoid them infecting other people. In earlier outbreaks, a family member could accompany the patient. But in 2014, to admit the huge number of patients, very big structures had to be built. The safety procedures had to be extremely strict, and it was impossible to allow family members. This large-scale approach scared patients and their families.

By the end of 2014, dozens of aid organisations, most of whom had been unexperienced with Ebola, were involved in different aspects of the response. The coordination of all those organisations, in multiple places in multiple countries, was extremely challenging. Some governments turned to authoritarian tactics to force patients and their families into compliance. That scared them even more.

The focus on the patients and their families, which had been so key to containing previous outbreaks, was completely lost in the enormous machine that the Ebola response had become.”

4. Did we learn anything from it?

“Many of the things that we consider as ‘lessons learned’ are things we knew before 2014, but that were forgotten. But we have also learned new things. We learned how we could take a simple, oral swab of dead people, to test whether they had died of Ebola. This allowed us to better understand the dynamics of the epidemic.

We also organised clinical studies and discovered a good vaccine against the Zaire strain of Ebola. And we learned from organising the clinical studies, so we were faster during the 2018 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In DRC, we found treatments with antibodies for the Zaire strain of Ebola.”

5. What needs to happen for the future?

“There are very concrete things we can improve. We should again allow a family member to accompany a patient to the Ebola clinic. We can protect them better now, with vaccination and drugs for pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Very sick patients should receive an antibody treatment much faster. Antibodies can be real lifesavers and the sooner a patient receives them, the better they work. We must adapt our models to make the best use of this option. And we need to continue looking for other treatments. The Ebola virus can provoke an inflammatory response that is so strong that it can kill the patient. If we had a drug to calm down that inflammatory response, we would save more Ebola patients.

We also must improve the follow-up of patients after their recovery. The virus can linger in the brain, the eyes, and the testes of survivors. Another type of drug, antivirals, can clean up the virus from these places. And six months after their full recovery, Ebola survivors should get a shot of the vaccine, to give their immune system another boost.

In the last 10 years, we have certainly made errors when we responded to Ebola outbreaks. Some errors were forced, some were unforced. But in general, we clearly have made progress, and there are good options for even more progress. The odds for a patient with Ebola in the next outbreak will be much better than they were 10 years ago.”