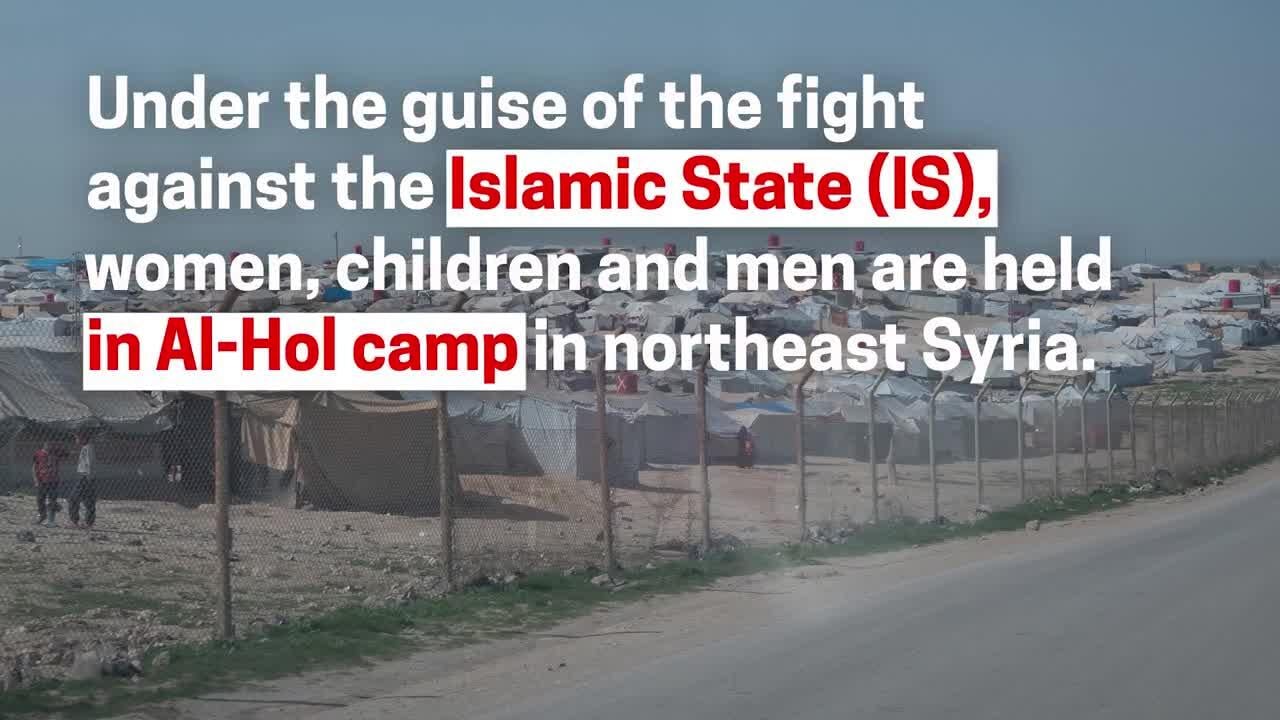

A new report by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) lays bare the cruelty of the long-term detainment of more than 50,000 people, the majority of whom are children, in Al-Hol, northeast Syria.

The deaths of two boys while awaiting approval for emergency medical care are just two of many tragic cases featured in the report Between two fires: danger and desperation in Syria’s Al-Hol camp.

A generation lost in Al-Hol camp

Children are not safe here

In February 2021, a seven-year-old boy was rushed to MSF’s clinic in Al-Hol with second-degree burns across his face and arms. Lifesaving medical care was no more than an hour's drive away, yet it took two days for his transfer to be approved by camp authorities. He died on the way to the hospital under armed guard, separated from his mother, in agony.

Just a few months later, in May of the same year, a five-year-old boy was hit by a truck and rushed to the same small clinic. MSF staff recommended he be referred to the hospital for emergency surgery. Despite the urgency, it took hours for his transfer to be approved. He died en route to the hospital, unconscious and alone.

Last year, 79 children died in Al-Hol detention camp, Syria. In 2021, 35 per cent of those who died in Al-Hol camp were children under the age of 16.

“We have seen and heard many tragic stories in Al-Hol detention camp in Syria, including children dying as a result of prolonged delays in accessing urgent medical care, and young boys reportedly forcibly removed from their mothers once they reach around 11 years old, never to be seen again,” says Martine Flokstra, MSF Syria operations manager.

“For children and their caregivers in Al-Hol, if they can access medical care, it is often a terrifying ordeal. Children who require treatment at the main hospital about an hour's drive away from the camp are escorted under armed guard, and in most cases without their caregivers, as they are rarely given approval to go with their children,” says Flokstra

Global Coalition must identify solutions

The camp was once designed to provide safe, temporary accommodation and humanitarian services to civilians displaced by the conflict in Syria and Iraq. However, the nature and purpose of Al-Hol has long deviated and grown increasingly into an unsafe and unsanitary open-air prison after people were moved there from Islamic State (IS) group controlled territories in December 2018.

“Members of the Global Coalition against IS, as well as other countries whose nationals remain held in Al-Hol and other detention facilities and camps in northeast Syria, have failed their citizens,” says Flokstra.

“They must take responsibility and identify alternative solutions for the people detained in the camp. Instead, they have delayed or simply refused to repatriate their citizens, in some cases going as far as to strip them of their citizenship, rendering them stateless,” she says.

It is thought that there are close to 60 countries who have citizens in Al-Hol and other related detention camps in Syria, including the UK, Australia, China, Spain, France, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Turkey, Sweden and Malaysia. Following some returns and repatriations, the total number of people in the camp now stands at around 53,000, of whom around 11,000 are foreign nationals.

“Despite the violent and unsafe conditions in Al-Hol, and more than three years after more than 50,000 people were moved there, insufficient progress is being made to close the camp,” says Flokstra.

“There are still no long-term alternatives to end this arbitrary and indefinite detention. The longer people are kept in Al-Hol, the worse it gets, leaving a new generation vulnerable to exploitation and without any prospect of a childhood free from violence,” she says.

MSF in Syria

Following 11 years of war, a record 14.6 million people need humanitarian assistance in Syria. It is the country with the largest number of internally displaced people in the world (6.9 million people), most of whom are women and children. Many have been displaced repeatedly and live in precarious conditions.

MSF operates in Syria where we can, but ongoing insecurity and access constraints continue to severely limit our ability to provide humanitarian assistance that matches the scale of the needs. Our repeated requests for permission to operate in areas controlled by the Syrian Government have not been granted.

In areas where access could be negotiated, such as northwest and northeast Syria, we run and support hospitals and health centres, and we provide healthcare through mobile clinics.