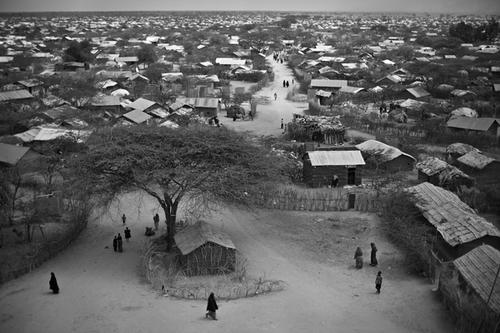

It is almost 25 years since the first people fleeing war in Somalia settled in Ifo refugee camp, in Kenya’s northeastern province, marking the beginning of what was to become the Dadaab refugee complex. Today, it is the largest in the world.

Options are limited for the thousands who call Dadaab home. Only a few months ago, one of the patients in the mental health programme run by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) committed suicide after his request to be resettled in a third country was rejected.

This tragic story is symptomatic of a place where hundreds of thousands of people are trapped, and where they live with little hope for a better tomorrow.

Some 350,000 refugees are today stuck in these camps in the semi-arid land bordering Somalia. They need travel authorisations to go anywhere else in the country, including to receive emergency medical care.

People in Dadaab remain nearly 100 percent dependent on humanitarian aid. A lucky few receive financial support from relatives living elsewhere, but for the majority, self-reliance is a pipe dream.

Living on emergency humanitarian aid generally means surviving on, if you are lucky, just 20 litres of water per day. It means living in a shelter made of plastic sheeting. It also means receiving a monthly food ration which may be cut without warning because of problems with funding or supply – both of which are subject to the “generosity” of the international community and to other humanitarian crises around the world, which absorb a portion of the aid budget and stocks available globally.

On 11 June, the World Food Programme announced – for the second time in seven months – that food rations for the refugee camps in Kenya would be reduced by at least 30 percent until September unless additional funding was secured.

For a refugee, what are the possible ways out? In theory they have three choices: to return voluntarily to their country of origin; to be relocated to a third country; or to be allowed to settle in the country where they first found asylum.

In reality, very few refugees in Dadaab apply for voluntary repatriation, because of ongoing war in Somalia. Many of the camps’ residents were born in Dadaab and have children who have little, if any, attachment to Somalia. Out of all those who apply for relocation to a third country, just a few dozen each month receive permission to do so. As for settling permanently in Kenya, for the refugees, the only option on the table is to remain inside the camps.

Dadaab, intended to be a temporary solution, has become all too permanent.

Currently the only strategy being seriously addressed is to return refugees to Somalia. Significant political attention, and funding, are being directed at “building a conducive environment in Somalia” that would favour refugees returning voluntarily.

It is unacceptable that this is the only strategy being seriously considered.

In the meantime, war still rages in Somalia, with the international community significantly involved. Clearly there is a need for other solutions, and it is up to the international community to support the Kenyan Government in proposing these.

Looking from a distance and avoiding responsibility should no longer be an option. It is time to share the burden.

The camps, meanwhile, are being portrayed as a security threat to Kenya, and the refugees have become scapegoats, forced to suffer the consequences of the global war on terror.

The deteriorating security situation has had a significant impact on the entire Kenyan population. The consequences are acutely felt in the refugee camps where the population is almost fully reliant on international aid. Only three weeks ago, MSF was forced to reduce its medical activities and pull out 42 of its staff for their own safety due to security incidents near the camps.

As time drags on, the situation in Dadaab is becoming increasingly untenable for those held within its boundaries. As long as refugees remain in Dadaab, they need to be provided with dignity, acceptable living conditions and reasons to have hope for the future.

Key governments, international stakeholders and the UNHCR need to face up to reality and to shoulder their responsibilities, in order to share the burden with the Kenyan government and people.

There are no easy answers to this decades-long discussion, and it is not our role to define the political solution, but possible alternatives exist. Why is there little incentive to allow more refugees to settle abroad, to relocate refugees to a safer area in camps of a more manageable size, or to develop opportunities for refugees to become more self-reliant?

Now is the time to make some tough choices and define some permanent solutions. Lives have been put on hold for a quarter of a century. We owe it to the hundreds of thousands who are forced to live in this open-air prison to return their dignity to them.