David Walubila Mwinyi is MSF's Medical Data Supervisor in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). He explains the situation in communities in DRC as they and MSF teams handle the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported here in DRC in early March, I wondered straight away how people learned about it, and whether it really was the first case. Had other cases had gone unannounced?

While there are low numbers of confirmed cases in DRC, this is more likely to be linked to the fact that very few tests are conducted in the country so far. There is currently only one laboratory that can analyse samples, and it is in Kinshasa. This lab can execute around 100 tests a day for a country of 80 million people.

Yet even if people manage access to a health facility to get a test, there are still huge logistical challenges in getting these tests from rural areas in South Kivu where I work, all the way to Kinshasa. Right now, the current average wait time for results is around a week.

One of my main worries when it comes to a pandemic of such proportions hitting DRC is misinformation, or lack of information. Far too often, people lack reliable sources of information, such as recognised medical experts who are working on this new coronavirus or the Ministry of Health.

Instead, they get their news from unchecked and often untrustworthy sources through social media, especially WhatsApp. These sources, in most cases, spread rumours rather than truth. Without clear official communications, it’s hard for everyone, even me, to discern the truth.

Misinformation also makes already vulnerable people even more vulnerable

Across the country – especially in the east where it is still volatile after decades of instability, war and conflict – we have several groups of already very vulnerable people. This includes people with diabetes or high blood pressure, and those who are already affected by some of the main killers of the region, like malaria and acute respiratory infections, or other diseases such as measles, cholera, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB), malnutrition or even Ebola.

As a medic, these are the people I am very worried about, as we still don’t even know how the virus will behave with these pre-existing conditions.

Many of these vulnerable groups face stigmatisation within their communities already. My concern is that if they become infected with COVID-19, and with so many myths and misinformation, they will face even further stigmatisation, making their lives all the harder.

My concern is that if people with pre-existing conditions become infected with COVID-19, and with so many myths and misinformation, they will face even further stigmatisation.David Walubila Mwinyi, MSF Medical Data Supervisor

Hunger makes ICUs seem a distant problem

To make matters worse, now that all borders are closed it is very difficult to not only get in everyday supplies, but also humanitarian staff and medical supplies to help fight COVID-19.

Medical equipment such as ventilators are desperately needed. There are only around 40 ventilators here in South Kivu and all of those are here in the capital Bukavu. These 40 ventilators will have to make do for a population of several million people. Quite simply, it’s not enough.

One might ask; have we thought about setting up intensive care units (ICUs) in the past? It’s a hard ask when people here in DRC are still dying of hunger. Hunger makes ICUs seem a bit of a distant problem. We do not even have the money to guarantee enough food for everyone, let alone ventilators.

We cannot compare DRC to Europe

This is one of the reasons why comparisons between the health system here in DRC to that of China or some other Western countries seem inappropriate in our context. Even when it comes to prevention measures, if you want people to wash their hands with soap and water, you need to provide them with soap and water. The reality here is many simply don’t have access to either. If they do not even have food to eat – why would they have soap?

It is especially difficult to explain to a community who has behaved in a certain way for generations to change customs to avoid negative health consequences. The introduction of measures like social or physical distancing is very difficult to not only explain but also implement.

People are accustomed to shake hands when they meet, especially with the elders. To not do so could be seen as a sign of disrespect, something against tradition and that can cause trouble, especially in rural communities.

If you want people to wash their hands with soap and water, you need to provide them with soap and water. The reality here is many simply don’t have access to either.David Walubila Mwinyi, MSF Medical Data Supervisor

There is a lot of scepticism from much of the population. Many people ask me how many people have died from COVID-19 here, compared to malaria, measles, and diarrhoea? The answers often exacerbate confusion, as the reality is its very few in comparison.

Even for the Ebola outbreak, it did not bring about movement restrictions such as those brought about by COVID-19, or measures such as physical distancing and masks becoming obligatory for all without a clear explanation.

We must learn from other epidemics and listen to communities

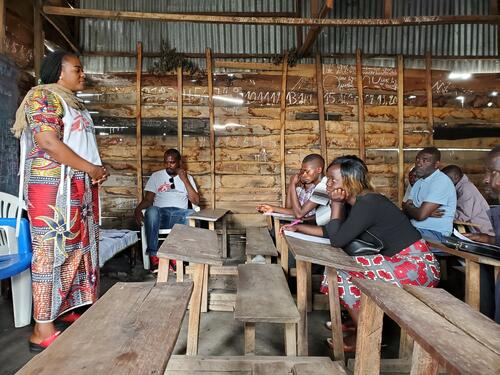

People are used to epidemics, sadly they are common here. There is something that we can – and should – learn from them. Most importantly, it is to listen to communities and acknowledge the traditions they hold so dear by talking with community leaders.

People are used to epidemics, sadly they are common here. There is something that we can learn from them. Most importantly, it is to listen to communities.David Walubila Mwinyi, MSF Medical Data Supervisor

We need to acknowledge that COVID-19 is just one of many medical or humanitarian emergencies they are faced with on a daily basis. During the Ebola outbreak, many people with other diseases like malaria, or women who were seeking pre-natal care, were told they could not be looked after because there was no money for that.

The money was only for Ebola. So many people started to believe that Ebola was just a business, that people came only to make money and medics were ignoring the actual needs of people.

We need to meet the people’s needs, by continuing to provide general healthcare across the country, earn their trust, and work together towards the end of the outbreak.

And finally, we must include the community in every step of the way, by not only listening to them but also by employing as many local people as possible to ensure we actively contribute to the overall well-being and prosperity of the entire community.”