In the past decade, MSF has carried out more than 100 vaccination campaigns, mostly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Sudan, Niger, Chad, and Nigeria. Many of these campaigns were among people displaced by conflict.

Conflict and low coverage, an outbreak’s best friends

Areas with low vaccination rates are most prone to measles outbreaks. These may include overcrowded, high-density settings such as refugee or displaced peoples’ camps, and contexts of war and conflict where the health system has collapsed.

For example, in Syria, war has destroyed a once well-functioning health system, causing vaccination coverage rates to plummet. A vaccine coverage survey conducted by MSF in Kobane (northern Syria) in June 2015 showed that only 17 per cent of children were fully vaccinated. For this reason, we have supported routine immunisation and vaccination campaigns in Syria since we began working there after war broke out in 2011.

A political and military crisis that started in 2013 in Central African Republic (CAR) destabilised the country and sent the country’s measles vaccination coverage rate tumbling. In 2012, 64 per cent of children below one year of age were vaccinated against measles. Two years later, that number was just 25 per cent.

Outside of conflict settings, areas with a weak or poorly-resourced health system are also vulnerable to measles epidemics. This is because there are often not enough resources mobilised to carry out routine immunisation activities and preventive vaccination campaigns, leaving vaccination coverage rates low.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is particularly prone to outbreaks of measles, as the country has remote areas, far from the central offices of health zones. Often, tough terrain complicates the logistics of reaching these areas with all the materials needed to carry out routine or outbreak vaccination campaigns.

Protection is the best method of prevention

Vaccination is the best protection against measles.

Children should be fully vaccinated against measles – with one dose of the vaccine by the time they're 12 months old and a second dose during the second year of life, usually between 15 and 18 months old. But this often doesn’t happen in fragile contexts where government vaccination programmes are disrupted or can’t reach everyone.

In these contexts, “catch-up” vaccinations are important. We often see older children with measles in refugee camps and expand our vaccination activities to include children up to the age of 15.

Starting a campaign before the first case of measles dramatically reduces the chances of an epidemic. That’s why we respond to the threat of measles outbreaks by conducting mass vaccination campaigns for vulnerable children.

For example, in CAR in 2016, we launched, in conjunction with the Ministry of Health, a massive vaccination campaign to ensure all kids under the age of five in the country were fully vaccinated. The campaign reached over 220,000 children who received vaccines against nine antigens, including measles.

We also vaccinate children against diseases – including measles – outside of vaccination campaigns; for example, when we treat children with malnutrition in our existing health structures and programmes.

MSF teams respond to the measles epidemic in DRC

Outbreak response

In an outbreak, our teams have to move fast as measles can spread so quickly to so many people; one sick person can infect up to 18 others. In refugee settings – where high numbers of people live in close quarters, often combined with a sub-optimal level of immunization coverage, making conditions ideal for fast spread of the disease – an outbreak is declared when there is a single case of measles.

For example, MSF teams saw a spike in measles cases among Rohingya refugees in the massive, overcrowded, densely-populated Cox’s Bazar refugee camp in southeastern Bangladesh in January and February 2020. Isolation wards in our hospitals were full; the Rohingya are particularly vulnerable to measles, due to a lack of routine vaccination before they fled Myanmar.

When an outbreak has been declared, any children with measles receive treatment and, if necessary, are transferred to a hospital. Our teams also immediately prepare a vaccination campaign as, even after the disease has started to spread, immunising people at risk can still reduce effectively the number of infections and deaths.

In the first six months of 2020, MSF teams had already vaccinated over half a million people against measles in response to three outbreaks we’re tackling in DRC, CAR and Chad.

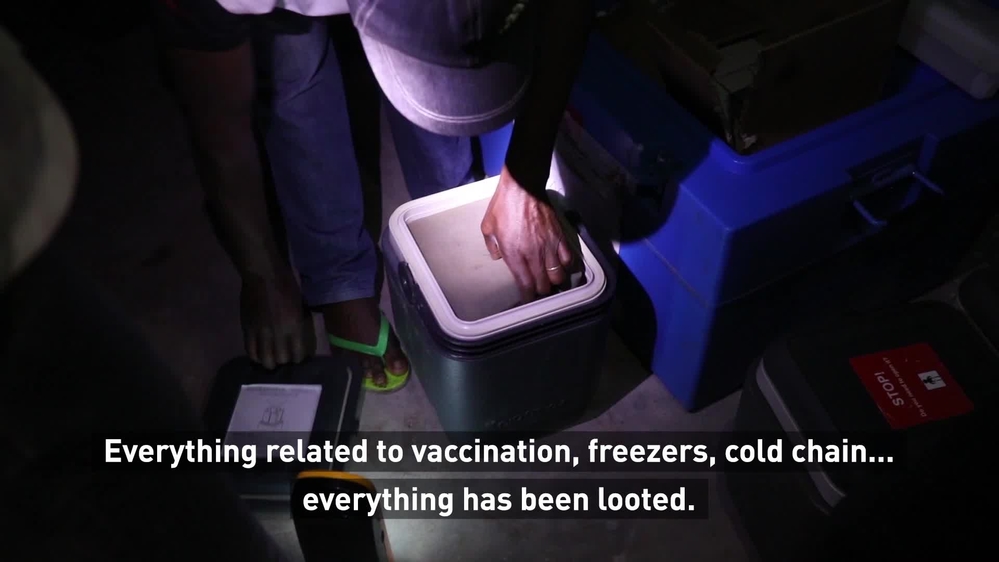

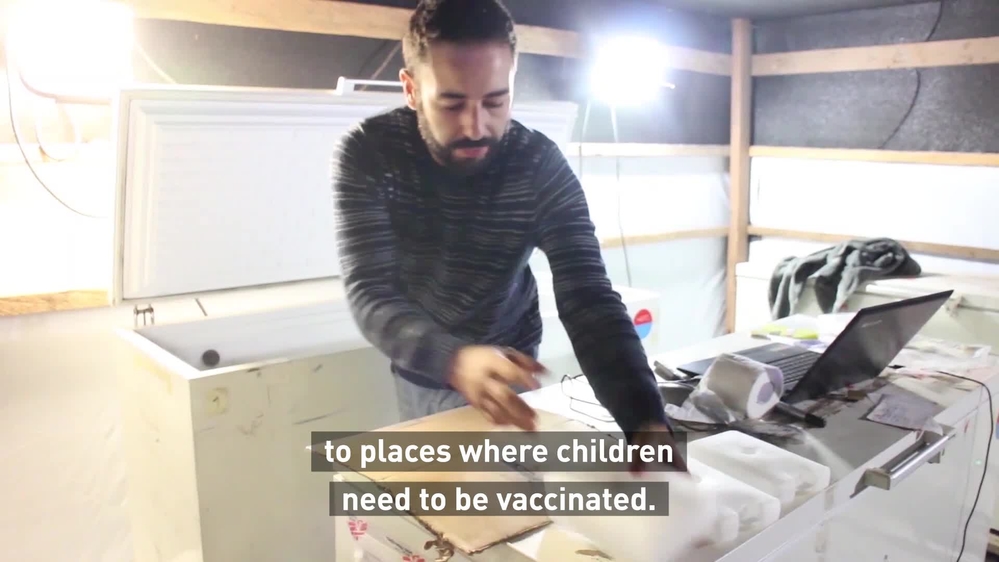

Vaccination campaigns can involve heavy logistics, especially in remote or resource-poor settings, as the measles vaccine requires a cold chain during transportation.

While community health workers spread the word with local leaders, nurses set up vaccination stations under trees or near schools.

Measles in DRC: 3 questions in 3 minutes

Emergency response teams

DRC is currently in the grips of one of the worst measles outbreaks the country has ever seen; from January 2018 to October 2019, MSF teams vaccinated around 1.5 million children across 30 different health zones and provided treatment and care to over 50,000 in 52 health zones.

In response, MSF had created a team – the Pool d’Urgence Rougeole, or Emergency Measles Pool – specifically dedicated to enhancing the response capacity during the current measles outbreak. Up until December 2019, the Emergency Measles Pool team worked along the axis of the Kasaï river, in the country’s southwest, to vaccinate children.

The Emergency Measles Pool team was disbanded at the end of 2019 and their activities handed over to an existing specialist emergency response team based in DRC, the Pool d’Urgence Congo, or the Congo Emergency Pool.

Logistical challenges

During an outbreak, besides setting up rapid vaccination sites in highly populated areas, we use mobile clinics and outreach teams in severely affected areas, with the aim of treating children within their local communities and vaccinating any children who have not previously been immunised against measles.

But the logistical constraints are huge. In some regions, the absence of paved roads make travel extremely difficult, particularly in countries with a rainy season.

It can take days to move between different areas, even in four-wheel drive vehicles. To reach more remote locations, we use motorbikes and even boats or canoes to transport large quantities of medicines, vaccines or therapeutic food.

Vaccines need to be kept within strict temperature limits, which requires setting up a cold chain. To keep vaccines cold for up to a day during vaccination campaigns, often in very hot temperatures, logisticians fill thousands of coolers with ice packs and load them onto trucks, cars, motorbikes or even boats, with all the supplies necessary for vaccinating thousands of children daily.

In regions that lack electricity, generators are used for the vaccine refrigerators.

Patient care

During outbreaks and in our paediatric outpatient clinics and hospitals, our teams provide medical care to children with measles, with particular focus on young children and those who are malnourished and more likely to become severely ill. Severe malnutrition, pneumonia and malaria can lead to complications and an increased risk of death for children with measles.

As measles has no cure, we focus on preventing dehydration, monitoring fever and managing complications, which include eye and ear infections, diarrhoea and pneumonia.

Children also receive vitamin A supplements, which has been shown to reduce measles deaths.