MSF operational update: Central Mediterranean

September – December 2017

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) continued to provide medical assistance to refugees and migrants along the Central Mediterranean route throughout the last few months of 2017. At sea, the dedicated search and rescue vessel Aquarius, run by MSF in cooperation with SOS MEDITERRANEE, rescued 3,645 people from unseaworthy boats in the Mediterranean and brought them to ports of safety in Italy. At disembarkation, MSF provided psychological first aid after tragic rescues, in addition to running several mental health and healthcare projects in Sicily. In Libya, MSF teams provided medical assistance to refugees and migrants arbitrarily held in detention centres nominally under the control of the Ministry of Interior.

Challenges working inside detention centres

In Tripoli, a huge increase in the number of people detained in October and November resulted in extreme overcrowding and a dramatic deterioration of conditions inside the capital’s detention centres. In some locations, up to 2,000 men were crammed together in one cell without enough floor space to lie down. Not only did overcrowding make it physically impossible at times for MSF teams to enter the cells and triage people detained inside, it further increased tension and violence. MSF team members were harassed and threatened, and there was mistreatment and violence against patients. From September to November 2017 the MSF team treated over 76 people for violence-related injuries including broken limbs, electrical burns and gunshot wounds.

Under these circumstances, the impact of MSF’s medical work was minimal. The team was able to help only a small percentage of all those in need of urgent treatment and it was not possible to follow up medical cases. Even so, more than 6,500 medical consultations in detention centres were carried out from September to December 2017. Most medical complaints were related to the conditions of detention, with overcrowding and inadequate latrine and drinking water provision resulting in acute upper respiratory tract infections, musculoskeletal pain and acute watery diarrhoea. MSF teams tried to focus on the most vulnerable people, such as pregnant women, children under five and people with life-threatening or potentially life-threatening complaints. A 24/7 emergency referral service was run with more than 150 patients referred to hospital for further medical treatment.

The number of detainees went down in December when thousands of people were mass repatriated to their countries of origin by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). Conditions inside detention centres in Tripoli improved and there was less mistreatment and violence against patients. In the detention centres that MSF visits, teams are now able to access cells to provide medical care to refugees and migrants that remain in arbitrary detention. The majority of physical and mental health problems requiring medical assistance still directly relate to the substandard conditions of detention.

Few international organisations are able to work in Libya due to widespread violence and insecurity. Those who do – including MSF – do not have full and unhindered access to all detention centres where refugees and migrants are being held. It is not possible to provide meaningful medical care in a system of arbitrary detention that causes harm and suffering. An overwhelming number of detainees have already endured alarming levels of violence and exploitation in Libya, and during harrowing journeys from their home countries. As such, MSF reiterates its call for an end to the arbitrary detention of refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in Libya.

Saving lives on the Mediterranean

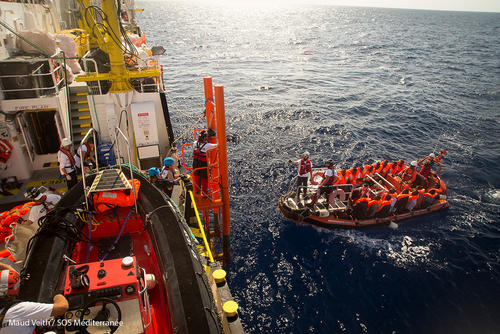

In the central Mediterranean, the number of refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants rescued at sea and brought to safety in Italy has fallen since last year. Aquarius, a dedicated search and rescue vessel run by MSF in cooperation with SOS MEDITERRANEE, rescued 3,645 people in the period September – December 2017. This is fewer people compared to the same period in 2016 when 5,608 people were brought to a port of safety in Italy.

The fall in numbers appears to be due to fewer boats leaving Libya. Reasons for this are unclear, though likely factors include the weather and political developments on the ground in Libya. There have been media reports that local militias are being paid off by Italy to prevent departures. Italian ships have been deployed in Libyan territorial waters as part of a broader European strategy to seal off the coast of Libya and “contain” refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in a country where they are exposed to extreme and widespread violence and exploitation.

Onboard Aquarius, MSF medics treated people for injuries they had suffered while in Libya and heard their accounts of violence and abuse at the hands of smugglers, armed groups, and militias. Around 12 per cent of all women rescued were pregnant and were cared for by the MSF midwife. There was a high prevalence of severe skin infections that required treatment with antibiotics and many patients suffered from severe chemical burns. As winter approached, there were multiple cases of hypothermia among those rescued. Rough sea conditions caused huge swells to crash over the aft deck of the ship soaking people sleeping there. In November, an unknown number of people drowned after an overcrowded inflatable dinghy suddenly capsized mid-rescue. The team on Aquarius launched all available floatation devices and life-jackets, and pulled as many people from the sea as they could but it was not possible to save everyone. No bodies were recovered.

Unclear future for refugees amid challenging rescue environment for Aquarius

Carrying out search and rescue activities in the Mediterranean is becoming even more challenging and complex. People who manage to escape Libya are increasingly being turned back at sea with the EU-supported Libyan Coastguard active in international waters. The MSF team onboard Aquarius witnessed refugees and migrants aboard unseaworthy vessels being intercepted by the Libyan Coastguard in international waters as EU military assets at the scene looked on. On 31 October, 24 November and 8 December, Aquarius was instructed to standby and was forced to watch as hundreds of people were pushed back to Libya by the Libyan Coastguard.

Although these interceptions are presented as “rescue operations” and are celebrated by the Libyan Coastguard and their EU partners, the reality is that migrants and refugees are not being returned to a port of safety. The crimes committed against refugees and migrants in Libya are widely known and have generated international outrage. Under no circumstances should migrants and refugees aboard vessels in distress in international waters be returned to Libya, they must be brought to a port of safety.

In September, Aquarius was instructed to conduct three rescues in international waters under the coordination of the Libyan Coastguard. These unprecedented and highly unusual instructions from the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) in Rome presented MSF with an impossible choice. Fortunately for each rescue, Aquarius was able to render the necessary assistance and took all rescued men, women and children to a port of safety in Italy. In that situation, it was not possible to verify who exactly was coordinating rescue operations as there are several entities operating along Libya’s vast coastline that claim to be the Libyan Coastguard. Contact points on land and at sea were unclear, as was the chain of command. As there have also been numerous violent incidents in recent months between the Libyan Coastguard and the few other remaining humanitarian organisations running dedicated search and rescue activities in the Mediterranean, the security of our team was paramount during these interactions.

It’s unclear what the future holds for refugees and migrants who find themselves along the Central Mediterranean route, but with Libya remaining riven by widespread violence and insecurity, with no unified government, a plethora of armed groups, and active fighting ongoing in several parts of the country, it does not look like an end to their suffering is in sight.

MSF has worked in Libya since 2011, providing medical consultations and referrals to refugees and migrants held in several detention centres nominally under the control of the Ministry of Interior. MSF works in centres in Tripoli, Khoms and Misrata and, in partnership with a local association, provides care to those who have survived and managed to escape from informal places of captivity in the Bani Walid area. MSF also runs a primary healthcare clinic in Misrata and supports women and child health activities in Benghazi.