Virginia is a Malawian sex worker living in Beira, Mozambique. She works to support her nephew and nieces after their parents died from HIV. Virginia recently found out she was HIV positive but is afraid to start treatment, for a number of reasons.

“A month ago, I found out that I had HIV. I don’t feel well. I haven’t gone out much. I’m just resting, sleeping,” Virginia saysName changed to protect identity. “I haven’t started treatment yet. I’ve heard that you become very sick from the side effects. I don’t know if I should start treatment in Malawi or here; I travel between the countries every month. And I don’t know how it works, if I can get treatment in both countries.”

“I can’t think or feel too much about my situation, because I have people who depend on me”, she says. “If I kept thinking about it, I would go crazy.”

Virginia’s story resonates with the experiences of many sex workers, people who use drugs, men who have sex with men, and prisoners. These groups are commonly referred to as ‘key populations’ and are disproportionally affected by HIV.

Key populations and their sexual partners account for 47 per cent of new HIV infections worldwide and 97 per cent of new HIV infections in eastern Europe and central Asia. One third of new HIV infections in eastern Europe and central Asia and in the Middle East and North Africa are among people who inject drugsUNAIDS report: Miles to go - Closing gaps, breaking barriers, righting injustices. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/miles-to-go_en.pdf.

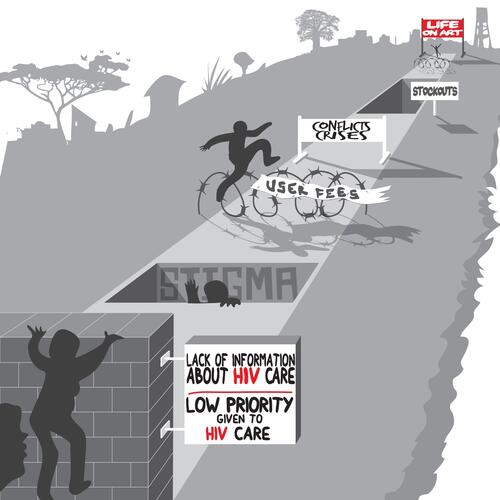

Despite their higher risk of acquiring HIV, key populations are often excluded from accessing HIV treatment and prevention, and comprehensive health services. Stigma, discrimination, social exclusion, violence and criminalisation are part of their daily struggles.

Driven into the shadows

“The main challenge for sex workers and men who have sex with men is stigma and discrimination,” says Farisai Gamariel, a peer MSM programme supervisor working with the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) project that supports men having sex with men (MSM) and transwomen in Beira, Mozambique. “People are not well informed about MSM and sex workers. This affects their self-esteem and makes it difficult for them to deal with challenges they face in accessing healthcare. One of our MSM patients, talking about going to the health centre, said: ‘They looked at me as if I was from another planet. I felt bad, and I swore that I would not step foot there again.’ Most cases of stigma and discrimination are never exposed, which also makes it difficult to fight against them. People are scared to report cases for fear of further victimisation.”

“In our projects in southern Africa, we have observed that sex workers and MSM are unable to access information on how to protect themselves against HIV and other diseases,” says Lucy O’Connell, MSF’s focal point for key populations in southern Africa.

“When they come forward to seek healthcare, they risk being hassled rather than helped. They are driven to work in the shadows, in unsafe situations, harassed by police, abused by criminal gangs, and suffering discrimination at clinics and hospitals.”

Sebastiana, a healthcare worker in MSF’s sex worker programme Beira, Mozambique, says: “Sex workers in Mozambique face a lot of discrimination. It is difficult for them to get medical attention in health centres. It is especially hard for those who come from Malawi or Zimbabwe. Whether they come from Mozambique or abroad, sex workers’ health cards, even those who are already on antiretroviral treatment, are often not recognised in clinics. We are working to spread awareness about the healthcare needs of sex workers. We’ve created a link between them and the health centres, to ensure that they can start and remain on treatment. There’s still a lot of work to do, but the situation is a lot better now. Now they are looked on as people, not just street girls who are sleeping around.”

Overcoming barriers to healthcare

MSF’s experience in Mozambique, Malawi and India shows that key populations need to have health services that are adapted to their lifestyles, otherwise they risk avoiding seeking medical treatment for fear of discrimination, from health staff and other people.

“In order to respond to the needs of key populations, it is crucial that we tackle the specific barriers preventing them from accessing care. We need to be open to and encourage locally adapted solutions to improve access to care. Long-term international and domestic funding is required, and key populations must be factored into the design and implementation of medical programmes.”Sidney Wong, MSF Medical Director, Amsterdam

“In overcrowded health clinics, sex workers and MSM groups don’t want to be recognised or identified, and so they tend to be the last to arrive. Standard clinic opening hours don’t work for them,” O’Connell explains. “Solving this requires locally adapted solutions. In one clinic in Beira, Mozambique, we added staff who were able to react opportunistically to their needs. Peers were tasked with navigating clients to clinics. We then ensured they were attended to at the clinic, as we risked never seeing them again.”

“For those who live outside urban centres, the cost of travelling to health facilities is another major deterrent. To overcome this, we find ways to reach out to them, instead of them having to find us. In rural areas like Nsanje, Malawi, we organise one-stop mobile clinics in hotel rooms, scheduled according to season and demand.”

Adapted solutions are also being sought by MSF’s teams in India. “Many of our patients in Manipur, India, are people who inject drugs,” Anita Mesic, HIV and TB programme adviser for MSF in Amsterdam, explains. “They endure a high burden of diseases – HIV, hepatitis C and tuberculosis – as well as psychosocial issues. Their complex medical needs require comprehensive, tailor-made medical programmes that integrate both prevention and care.”

If we do not respond to the specific health needs of key populations, we won’t be able to curb the HIV epidemic.

MSF’s key population activities in Malawi and Mozambique

Between Mozambique and Malawi, MSF provides adapted peer-led packages of HIV and sexual and reproductive healthcare services at community level, including PrEP, HIV testing and treatment for sex workers and men who have sex with men (MSM) in six project sites located along the main transport routes. Over 9,000 sex workers have been enrolled in these projects since 2013 and 330 MSM since 2016. The development of services has been guided by World Health Organization recommendations on key populations.

MSF’s key population activities in India

MSF has been working in Manipur, India, since 2004. In May 2018, 2,035 people living with HIV were receiving ARV treatment at MSF facilities. At the clinics located in Churachandpur, Chakpikarong and Moreh (on the Indo-Myanmar border), MSF provides free, quality screening, diagnosis and treatment for HIV, TB, hepatitis C and co-infections. MSF also provides pre and post-test adherence counselling to ensure a successful outcome for the patients. In addition, MSF is treating HCV patients (mono-infected) in an opioid substitution therapy (OST) centre in Churachandpur, and treating the partners of co-infected patients. In 2017, MSF started hepatitis C treatment at the district hospital in Churachandpur in collaboration with Manipur AIDS Control Society to introduce a simplified model of care.