Violence which spread throughout Borno state, in northeast Nigeria, has forced people like Adama out of their homes. Adama now lives in a camp for displaced people in Pulka, a small garrison town located 115 kilometres southwest of Maiduguri, the state capital. She is only one of around 37,000 displaced people trying to survive here.

“We have to be grateful that we now have water, but we don’t usually have enough water when we enter the dry and hot season,” says Adama.

The dry, hot season in the part of western Africa known as the Sahel usually lasts from November until May. Not a single drop of rain touches the cracked earth for nearly seven months, while the Harmattan, a dry wind coming from the Sahara Desert, brings sand and hot air during the day and cold air at night.

Lack of clean water leads to illness in Pulka

Lack of water leads to lack of resources, illness

The temperature can go from 9 to 35 degrees Celsius in a day. This extreme climate was challenging for local farmers even before the armed conflict in Borno began. The situation now, after 10 years of violence, has worsened due to the high number of displaced people, limited farming land and clean water, and a lack of other basic resources and means to produce food.

Even if people somehow manage to produce food, often they have to exchange it for water. In some places, groups are making money by selling water from pre-existing water points or those built by humanitarian organisations, to displaced people, sometimes by community leaders. Often the only water that people can get is polluted or not properly treated with chlorine, which can cause health problems, especially among children who are one of the most vulnerable groups.

Organisations in charge of water and sanitation in the area recently built an artificial lake, or a ‘pond’ as it is called by locals. However, due to a chlorine treatment unit not working and no existing connection to the pumping system, the pond has had little impact, and is mostly used by people to do laundry or water their cattle.

“The problem of insufficient water is very serious,” says Fati, another displaced person who has settled in Pulka. “When we have money, we buy water from the well, but if we don’t have any, we have to fetch it from the pond and this makes our children sick.”

Water trucking was also introduced by different water and sanitation organisations as a temporary solution. However, logistical issues due to frequent closures on the main road to Maiduguri mean this option is not reliable, leaving Pulka residents with no choice but to use the pond. Even when there is enough water, the bigger issue is the quality of this essential resource.

Unless water and sanitation organisations in Pulka act right now, we will witness even more suffering by people there.Siham Hajaj, MSF head of mission in Nigeria

People are trying to find a way to make ends meet

Most people do not have the arable land or water to farm or grow food in the displaced people’s camps, because there is not enough space; the situation outside the camps is also too dangerous. Farming land is located on the periphery of Pulka, outside the trenches and fences that make the town more resistant to attacks and intruders, but which also cuts off people from the outside world. In such conditions, stress, tension, even conflict, among people is to be expected.

“Those of us with four or five jerry cans are usually asked to wait for the pushcart owners from the community to get water before we can get water,” explains Maryam, another camp resident. “There are men who are in control of the water points; they are the ones that usually tell us to wait our turn in the queue.”

“But we don’t usually wait,” Maryam continues. “We force our way to get the water whenever the person at the water point has had their fill. And this, in most cases, leads to scuffles and injuries.”

Polluted or untreated water badly affects children

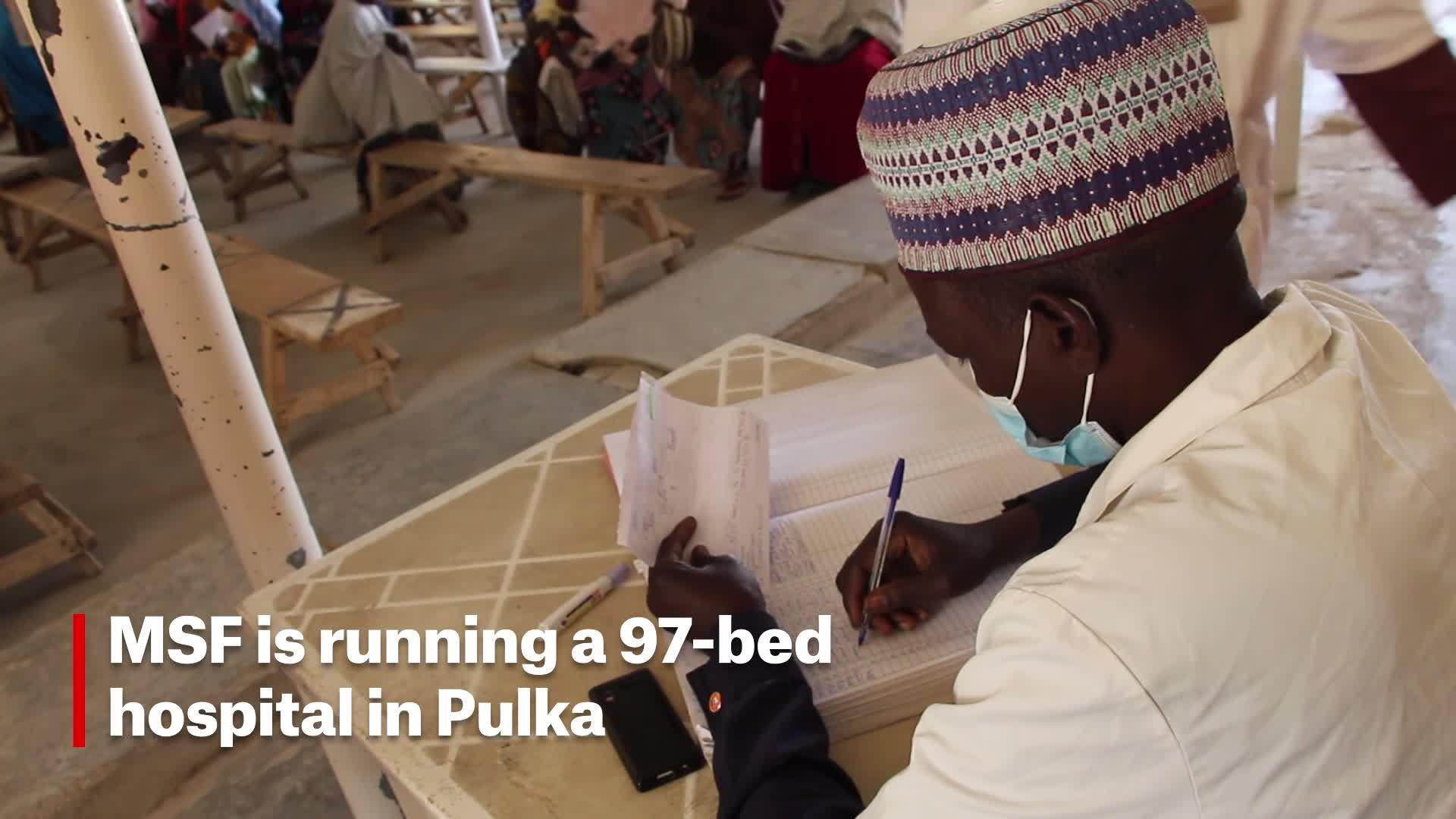

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) runs a 97-bed hospital in Pulka, which offers free-of-charge general and specialist healthcare to all residents, including displaced people. Roughly 58,000 patients were treated in the hospital’s outpatient department in 2020; respiratory tract infections and polluted water-induced diseases are the vast majority of illnesses treated. MSF also conducts regular health education in the displaced people’s camps about the importance of clean water, especially when water is a scarce and very valuable resource.

Cecilia came to the hospital because her baby had diarrhoea.

“He has abdominal pain and a runny nose. The abdominal pain makes him pass watery stools,” says Cecilia. “We usually get our drinking water from the solar borehole in the morning. If we didn’t go in the morning, we wouldn’t get any water.”

“We sometimes drink the water from the local pond, but only if we have the chemicals to treat it,” Cecilia continues. “But for now, we don’t drink the water from the pond because children play and have their bath in it.”

Mohammed, another patient in the hospital, called on water and sanitation providers to take serious measures to improve the current conditions.

“We get our water from the pond. But the water has lots of dirt in it; it’s not treated and that is why we constantly have abdominal problems and related illnesses,” says Mohammed. “Our major problem here in Pulka is the water, as it gives us abdominal pain. For about two weeks now, I’ve not been feeling well. We are appealing to those in charge to fix our boreholes, as some of them are not functioning.”

“There is a clear lack of coordination and communication among different water and sanitation organisations here, which impacts the situation,” says Siham Hajaj, MSF head of mission in Nigeria. “The people of Pulka need immediate action from humanitarian organisations, which need to improve both the access to, and the quality of, the drinking water. Unless water and sanitation organisations in Pulka act right now, we will witness even more suffering by people there.”