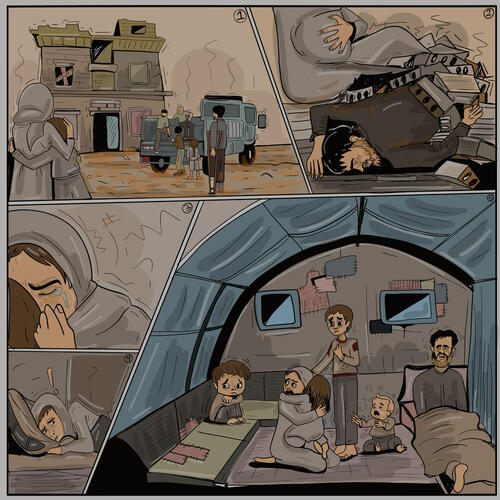

“We live in a tent – the children are afraid of houses and buildings,” says Hind, a mother of five in Afrin, in northwest Syria’s Idlib province. “We are very tired.”

Where can you find refuge when your home is no longer safe? How can you comfort your children when they live in fear of the ground rocking beneath their feet?

These are some of the questions in the minds of people in northwest Syria, a region grappling with the impact of economic crisis and more than a decade of war, compounded by the aftermath of the devastating earthquakes that struck northwest Syria and south Türkiye on 6 February 2023.

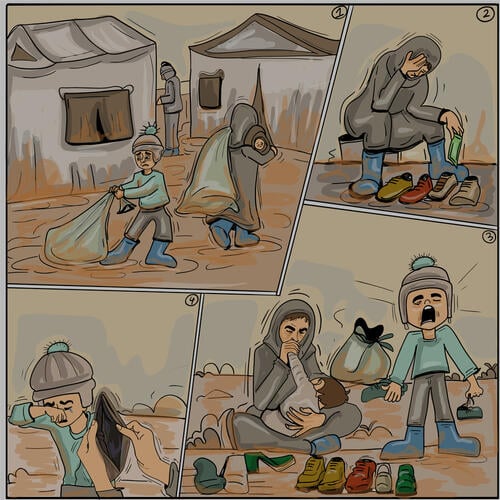

“The earthquakes created more poverty, homelessness and displacement, and caused a decline in people’s living conditions, worsening the economic situation and the functioning of the education system and causing damage to infrastructure,” says Thomas Balivet, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) head of mission in northwest Syria.

“In addition, thousands of children lost caregivers or suffered physical injuries and amputations. All of these factors have exacerbated the mental health situation for thousands of people across the region,” he says.

Before last February, many people in northwest Syria had already been displaced from their homes by the war. In the aftermath of the quakes, they found themselves destitute – without shelter, food, clean water or other basic essentials.

When I entered, I was shocked by the sight of the wounded and corpses in the rooms and corridors of the hospital. I was no longer able to stand – I sat on the ground and burst into tears.Omar Al-Omar, MSF mental health supervisor in Idlib

“We left our hometown in Saraqib, east of Idlib, because of the war and constant shelling, and after years of being displaced and looking for safety, we settled in Afrin, further north,” says Hind.

“The house we stayed in had no walls – we hung up blankets for shade and privacy. My husband used to work but we barely had enough to eat. Then the earthquake happened and we lost everything again.”

The first quake, of magnitude 7.8, left a swathe of destruction reminiscent of the war damage that already scarred northwest Syria.

Omar Al-Omar, MSF mental health supervisor in Idlib, remembers the first hours after the earthquake. “At the break of dawn, I went down to Salqin, a town in Idlib province. I saw entire buildings collapsed and turned into rubble,” he says.

“What hurt me the most was hearing the voices of people under the rubble asking for help, while I was unable to provide assistance. Then I went to Salqin hospital, which is co-managed by MSF.

“When I entered, I was shocked by the sight of the wounded and corpses in the rooms and corridors of the hospital. I was no longer able to stand – I sat on the ground and burst into tears,” says Al-Omar.

“In the hospital, we could feel the aftershocks, and every moment large numbers of wounded and injured people entered the hospital. It was a night that will remain engraved in my memory until the last day of my life.”

Even before last February, the healthcare system in northwest Syria was struggling, with underfunded medical facilities and limited services. The earthquakes damaged 55 health facilities, leaving them unable to function fully.

Since the earthquake, cases of post-traumatic stress disorder and behavioural problems have surged, especially among children.Omar Al-Omar, MSF mental health supervisor in Idlib

As well as medical assistance, people across the region needed toilets, showers, heating systems, winter clothing, generators, blankets, hygiene kits and cleaning products.

In the hours following the first quake, our teams provided emergency medical care and immediately started distributing our existing stocks of essential relief items. In the following days, we sent 40 trucks loaded with medical and non-medical items to the area, including food and shelter materials.

Meanwhile MSF water and sanitation experts constructed toilets and showers for earthquake survivors and provided them with clean drinking water.

“Following the acute phase of the emergency response, our focus shifted towards providing shelter, food and relief items, ensuring access to healthcare as well as water and sanitation services,” says Balivet. “The lack of these basic necessities has had a profound impact on people's mental health.”

One year on, the physical destruction caused by the quakes is less visible than before, but the impact on people’s mental health is stark.

“Since the earthquake, cases of post-traumatic stress disorder and behavioural problems have surged, especially among children,” says Al-Omar, “in addition to panic attacks, various types of phobias and psychosomatic symptoms.”

Addressing people’s mental health needs

MSF has provided mental health services to people in northwest Syria since 2013. After the earthquakes, we launched a comprehensive mental health initiative as part of our emergency response.

Mobile teams of mental health counsellors provided psychological first aid, while specialist counselling was offered for moderate and high-risk patients, in 80 locations across the region.

We also ran sessions to help people deal with both their immediate psychological reactions and the emotions that come later. Our teams provided a total of 8,026 individual mental health consultations in the aftermath of the earthquakes.

Investment in improving the living conditions of the people of northwest Syria is essential. Only by addressing the root causes of suffering can we hope to pave the way towards recovery.Thomas Balivet, MSF head of mission in northwest Syria

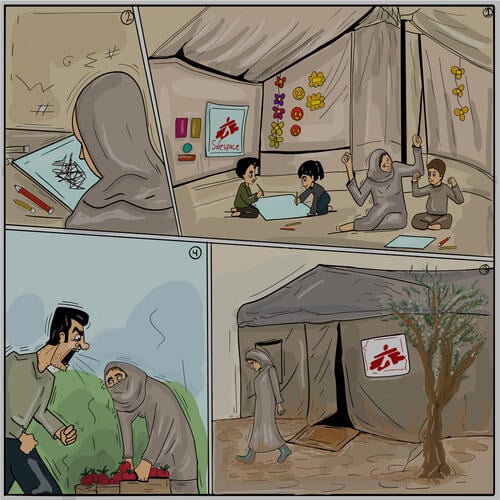

Safe spaces for women and children

We also set up a ‘safe spaces’ programme in four locations in northern Aleppo and Idlib provinces, in collaboration with partner organisations, to provide places where women and children could take a moment of respite from the harsh reality outside.

These activities are still running, with three additional sites added in Idlib province. Within these dedicated tents, women and children engage in games and activities, such as drawing, take part in group sessions, or simply sit and rest.

Whether engaged in quiet contemplation or lively conversation, the women and children in these spaces find a refuge where they can momentarily disconnect from the weight of their troubles and simply breathe.

Some 25,000 women and children have used the safe spaces; MSF teams also referred 1,900 of the women and children to other organisations to receive follow-up treatment for physical or mental health issues.

Hind, who frequently visits one of MSF’s safe spaces, says: “When I come inside the safe space, I forget everything, I forget the agony and fear. My children come with me and play. We all forget the fear, we all forget what happened after the earthquake.”

Living amidst the rubble of the conflict and the earthquakes, people in northwest Syria still need clean water, food, shelter and access to essential healthcare.

“Investment in improving the living conditions of the people in northwest Syria is essential,” says Balivet. “Only by addressing the root causes of suffering can we hope to pave the way towards recovery.”