“I felt as if I was on the brink of death. I had no idea what was happening to me,” recalls Muhammad Ahsan, sitting anxiously outside the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) hepatitis C facility in Machar Colony, Karachi, in Pakistan, awaiting his third post-treatment test. “I was so weak, and I couldn't even move. My family was worried: my children were young, and I was the only breadwinner. I felt like I was leaving them behind.”

Ahsan’s journey began eight years ago when he was diagnosed with hepatitis C. At the time, he was a robust 68kg, but his weight soon plummeted to a mere 37kg. Originally from Gujrat, over 1,200 kilometres away from Karachi, he had spent 25 years in Soldier Bazar, Karachi, before returning to his village last year.

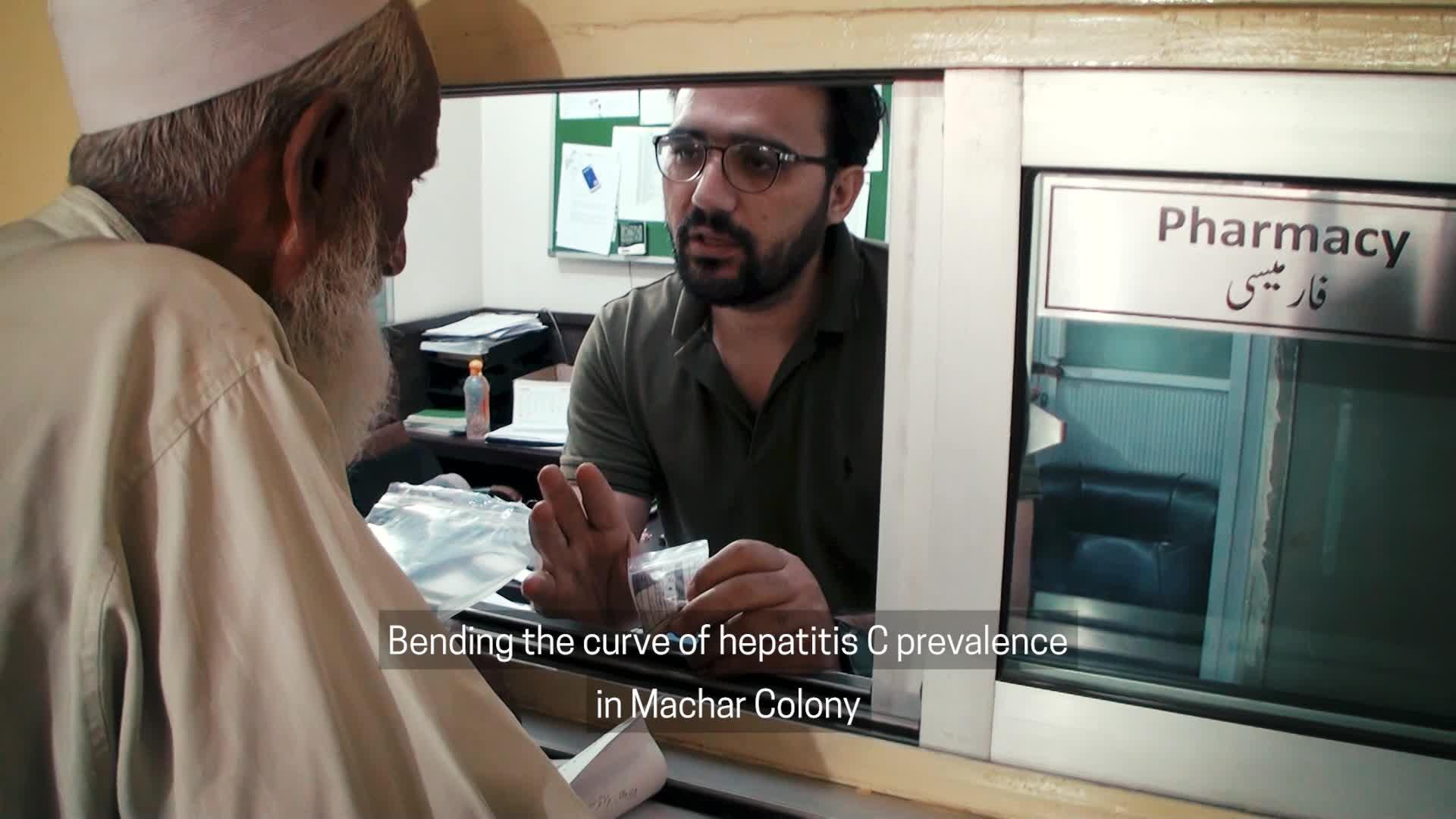

Bending the curves

Initially, he experienced symptoms such as pain in the back of his legs and frequent hiccups after eating. A doctor suggested a liver test, which confirmed he had hepatitis C. The re-use of needles and razor blades, unsafe healthcare practices, and sharing everyday household items, such as combs or toothbrushes, are the most common risk factors for the spread of hepatitis C virus (HCV), as it is transmitted through blood.

If left untreated for too long, it can progress to end-stage liver disease and even liver cancer. Commonly, people are screened for HCV infection only when they start showing symptoms of liver disease, which is often too late. Considering the prevalence of HCV infection in Pakistan, all people should undergo screening for it at least once a year, regardless of signs and symptoms.

Ahsan first sought treatment at Jinnah Hospital, where he underwent a three-month course of medication. Unfortunately, the treatment was ineffective.

“I was devastated,” says Ahsan. “I had pinned all my hopes on that treatment, and it failed me. I felt like I was running out of options.”

Desperate for a solution, he turned to a hakeem (a traditional healer) in Layeh, who provided him with herbal medicine. After taking these herbs, “I felt better, but my hepatitis C tests continued to show positive results on the PCR [polymerase chain reaction] test,” says Ahsan.

Ahsan’s life was put on hold as he battled hepatitis C. Despite his determination to provide for his family, he was forced to rely on loans from friends to cover basic needs. His inability to work took a toll on his family’s well-being, leaving them in a vulnerable position.

Last year, one of his friends in Karachi told him about the free treatment available at the MSF clinic. Encouraged by his friend’s successful treatment in MSF’s Machar Colony facility, Ahsan decided to give it a try.

“I was desperate for a cure, and I had heard good things about MSF from my friend,” says Ahsan. “I knew it was my last chance, and I was willing to try anything.”

After an initial assessment, medical examination, and tests, he started his HCV treatment. The first line of treatment for hepatitis C infection at the MSF clinic is a 12-week course of the direct-acting antivirals sofosbuvir and daclatasvir.

“In some patients, the hepatitis C viral infection is resistant and cannot be cured with this treatment course,” says Dr Natasha Mustafa, who works at the MSF clinic in Machar Colony. “This can be because the virus is resistant to the first-line treatment or the patient struggles to adhere properly to the medication regimen, including issues like discontinuing the treatment before it’s finished.”

Despite completing three courses of treatment, Ahsan’s post-treatment tests kept showing positive results for hepatitis C.

“I was anxious and worried, but the MSF staff were kind and supportive,” says Ahsan. “They treated me with respect, unlike other hospitals where I felt like just a number.”

Unfortunately, some patients are infected with a resistant virus or develop resistance to direct acting antiviral drugs and cannot be cured, even with second-line medication.Dr Natasha Mustafa, works at the MSF clinic in Machar Colony

Dr Mustafa explains that if the hepatitis C infection persists for three months after completing the initial treatment, then it is time to proceed with second-line treatment.

“This involves a different combination of medications, including sofosbuvir and velpatasvir. The treatment cycle is repeated: a 12-week treatment course followed by a 12-week drug-free gap and then another PCR test,” says Dr Mustafa. “Unfortunately, some patients are infected with a resistant virus or develop resistance to direct acting antiviral drugs and cannot be cured, even with second-line medication. For these patients, there is a possibility for a third-line regimen, a combination pill of sofosbuvir, velpatasvir and voxilaprevir.

After moving back to his village last year, Ahsan continued his treatment at the MSF clinic. “It was a struggle, but I knew I had to keep fighting. I had to be strong for my family, for my children.”

Finally, after his third post-treatment test, Ahsan received the news he had been waiting for – his report was negative, indicating that he had been cured of hepatitis C.

MSF has been a dedicated healthcare provider in Karachi’s Machar Colony since 2012. In 2015, MSF established a comprehensive hepatitis C programme, offering a full spectrum of services – screening, diagnosis, treatment, health education, and patient support – all under one roof at the basic healthcare level.

As part of our operational research aimed at eliminating hepatitis C in Machar Colony by the end of 2024, we have implemented an innovative ‘bending the curve’ model of care. This ambitious initiative focuses on scaling up screening and testing for all residents aged 12 and above, aiming to identify and treat cases swiftly to curb the spread of the virus.

In 2023 alone MSF conducted 45,377 rapid diagnostic tests and 6,480 PCR tests, mobilised 58,078 people for awareness and testing, initiated lifesaving antiviral treatment for 1,942 patients, and ultimately cured 981 people of hepatitis C.