Who are the Rohingya?

The Rohingya are a stateless ethnic group, the majority of whom are Muslim, who have lived for centuries in the majority Buddhist Myanmar, mostly in the country’s north, in Rakhine state. However, Myanmar authorities contest this; they claim the Rohingya are Bengali immigrants who came to Myanmar in the 20th century.

Described by the United Nations in 2013 as one of the most persecuted minorities in the world, the Rohingya are denied citizenship under Myanmar law.

Due to decades of violence and persecution, generations have lived in fear. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled to neighbouring countries, including Bangladesh and Malaysia, either by land or by boat.

Prior to the military crackdown in August 2017, roughly 1.1 million Rohingya people lived in Myanmar. Around 600,000 remain in Rakhine state today, including 140,000 Rohingya detained in displacement camps.

Over 2 million Rohingya refugees live as displaced people – mostly across Asia and the Middle East.

The Rohingya: What does it mean to be 'stateless'?

Myanmar

Despite generations of residence in Myanmar, under the 1982 Myanmar Citizenship Law, the Rohingya are effectively excluded from full citizenship, leaving them stateless.

As a result, they are denied freedom of movement, access to healthcare, education and livelihoods. Rohingya in Myanmar for decades have been, and continue to be, persecuted.

I have hope my children can get an education one day. And I want a good shelter so I can live a normal and enjoyable life... When I lived in my own house, I felt secure.Zaw Rina, a Rohingya woman who’s lived for 10 years in a displaced persons’ camp in Rakhine state.

2017 violence and exodus

Government military operations targeting Rohingya scaled up in August 2017. The government response was in retaliation for a series of attacks claimed by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army against police stations and a military base.

Rohingya who fled told of homes and villages being burnt to the ground, often with entire families still locked inside. Women and girls were raped, and men and boys rounded up and shot. Children were beaten to death.

In December 2017, surveys we conducted in the refugee camps in Bangladesh found that at least 6,700 Rohingya - in the most conservative estimates - were killed by violent means in Myanmar between 25 August and 24 September 2017. At least 730 were children under five years of age.

The military came to our part of town around 6pm and said: ‘Leave the village before 8am tomorrow. Everyone that stays will be killed.’61-year-old MSF Rohingya patient in Bangladesh, after fleeing Myanmar

Entire villages of people fled Rakhine state; around 770,000 Rohingya crossed the border into Bangladesh, arriving in camps in Cox’s Bazar.

A struggle to survive

Rohingya who have stayed in Myanmar live in terrible conditions. Life for those in displaced people’s camps is cramped and squalid, and they are reliant on humanitarian assistance.

People living outside of camps in Rakhine state struggle to afford food. Both people living in camps and outside them lack access to clean drinking water, leaving them at risk of water-borne diseases and skin infections.

Conditions since the February 2021 military coup have not improved for Rohingya; there is significant economic turmoil in the country, with the local currency falling in value, pushing up the price of imports. Fuel and food have both increased in price, particularly in Rakhine state where there is a reliance on transporting goods in from other areas of the country.

What is MSF doing?

MSF provides reproductive and basic healthcare, treatment for sexual and gender-based violence, health education, mental health support, and referrals for emergency and specialised treatment to Rohingya still living in Myanmar, including in camps in central Rakhine state and in village settings in the north.

Bangladesh

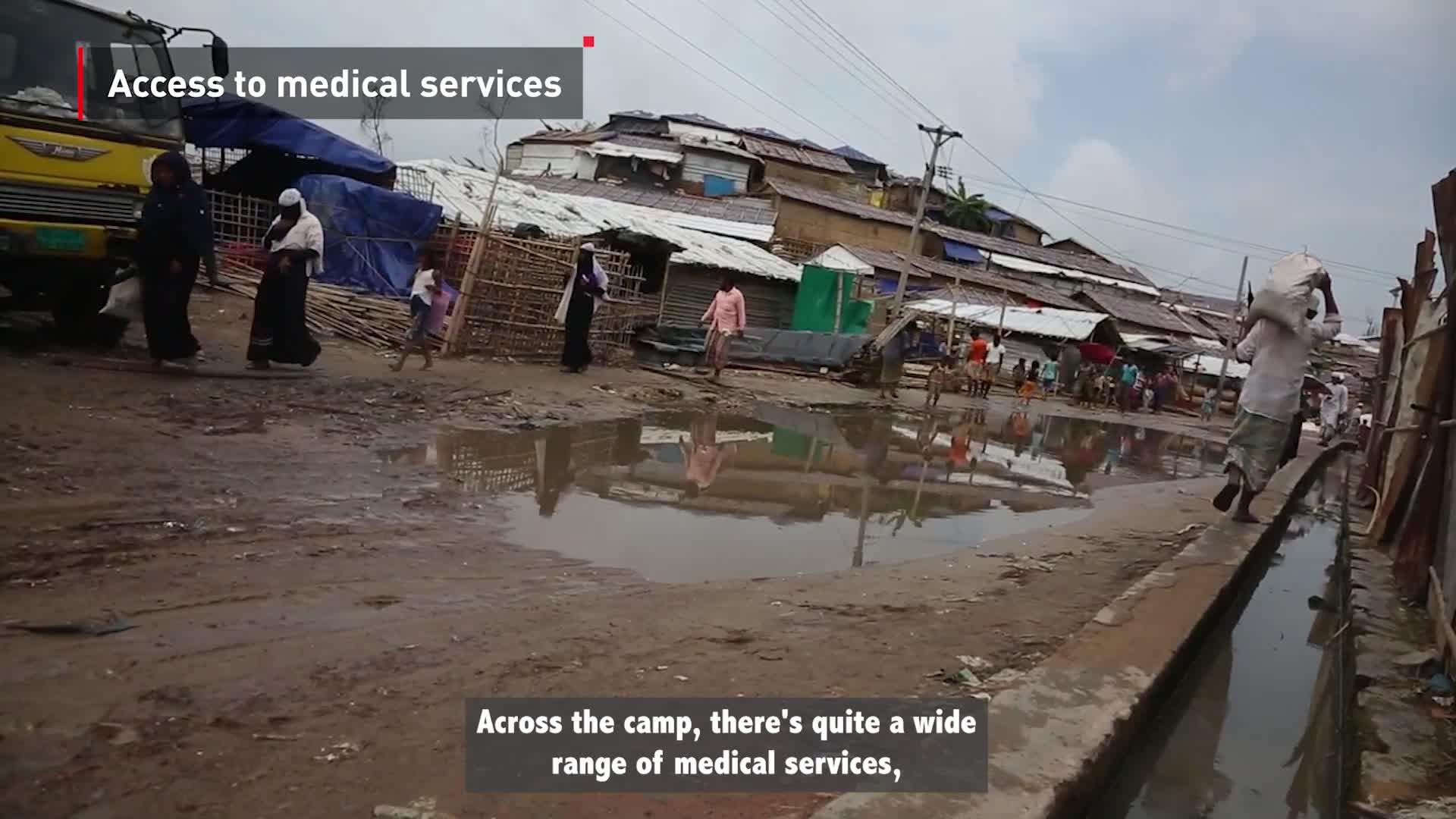

Nearly 1 million Rohingya live in Cox’s Bazar, southeastern Bangladesh, in what is one of the biggest, most densely populated, refugee camps in the world.

Over three-quarters of a million people arrived in Cox’s Bazar in the wake of the terrible violence against the Rohingya in Myanmar, in August 2017.

Dire living conditions, increasing restrictions

In the five years since the influx of arrivals, conditions in the camp have become steadily worse. ‘Temporary’ shelters have been built on slopes in an area prone to annual flooding. They’ve been built very close together, meaning tasks like cooking are risky; outbreaks of fires – sometimes resulting in deaths – are common.

Water and sanitation services are absolutely dire. There is insufficient water supply to meet people’s needs. Toilets are often overflowing. They are also often located far away from some residences and don’t all have lockable doors, posing a security risk for women and girls. There is a shortage of containers for disposal of household waste, resulting in rats and mosquitoes proliferating.

Cox’s Bazar: A precarious life for the Rohingya

In the past, Rohingya could move freely in the camps, and they could also work. Since 2019, the camps have been fenced with barbed wire, with checkpoints at entrances and within the camps. Rohingya now face restrictions on leaving the camp and even moving between different camps; there is almost no access to employment, education or livelihood opportunities.

When we first arrived here, we were very hopeful. But now, we feel stuck. Life has become difficult. Whenever I go out, I am searched [by the guards]. I cannot even visit my children.Mohamed Hussein, a Rohingya refugee living in Cox’s Bazar.

In cramped, crowded, unsanitary conditions, a number of diseases are rife within the camps. In November 2017, an outbreak of the long-forgotten disease diphtheria was reported among refugees; MSF teams treated thousands of people. Dengue, diarrhoeal diseases and skin infections are common amongst Rohingya living in Cox’s Bazar.

What is MSF doing?

We work across nine sites in Cox’s Bazar, where we provide general healthcare, treatment of chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, emergency care for trauma patients, mental health and women’s healthcare.

MSF also provides key support to water and sanitation activities in the camps, such as latrine de-sludging, faecal sludge treatment, maintenance of hand pumps, tube wells, and water networks, as well as hygiene promotion.

Malaysia

Rohingya refugees have been coming to Malaysia for more than 30 years, making the perilous journey across the Andaman Sea. However, in Malaysia, the life of refugees continues to be a struggle for dignity and acceptance.

Refugees, asylum-seekers and stateless people are criminalised by domestic law and unable to access healthcare, education or work. Even those registered with the UN’s refugee agency (UNHCR) are not allowed to work or access education and healthcare.

All Rohingya refugees face the constant risk of arrest and detention, and must often resort to informal dirty, dangerous and/or difficult work to survive.

I don’t have enough money to pay for housing. I sleep where I can; I survive as best I can.Shor Muluk, a Rohingya refugee in Malaysia

Pushed back or detained

Our teams have seen an increase in xenophobic sentiment against Rohingya since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, which coincided with a change in government. Following several new arrivals by boat in early 2020, the government took a hard-line stance against Rohingya refugees by pushing back boats from reaching the coast.

The government also tightened land and sea borders and increased raids by immigration authorities throughout the country, targeting areas where refugees and migrants reside and work.

Rohingya refugees and asylum seekers who have recently arrived by boat have been charged in court and are currently in prison or immigration custody. Our teams have attempted to access these people to provide medical assistance and mental health support, but we were denied access.

What is MSF doing?

In Malaysia, our teams provide medical care and mental health support to the Rohingya through our clinic in Butterworth, our mobile clinics in Penang and Kedah, and in our activities in detention centres. We also refer patients to secondary and tertiary healthcare, and support an increasing number of victims of sexual violence, including women and men who have been trafficked.