Despite the high level of trauma experienced by the Rohingya in Myanmar, only a small proportion of the population in Bangladesh currently has access to specialised mental health services.

In July-August 2018, celebrated photographer Robin Hammond and MSF organised a six-day workshop in Kutupalong refugee camp, in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar district. With this 'In my World' storytelling workshop, Rohingya refugees were encouraged to tell their own stories relating to mental health through photography.

This photo story highlights some of the people we met and the stories they told.

Malek and Sofura

Sofura lives with an undiagnosed mental health issue. Her granddaughter's husband, 20-year-old Malek, and the rest of the family care for her as much as they can. They left Myanmar together on 26 August 2017, arriving in Bangladesh on 3 September. They fled when they saw the military and the fires they had lit approaching their village.

Sofura always had episodes where she would abuse family members or go wandering for days, Malek explains. In Rakhine, with close-knit society and family members, Sofura’s wanderings were not problematic. There would always be someone close by to keep her out of harm’s way.

Camp life is different, Malek explains. “Here it’s very tough [taking care of her]. Here there are many vehicles and she might be lying in the road and a bus could come by and kill her. If people call her a kidnapper, they might kill her. In Myanmar there were fewer vehicles and people knew her.”

Jamil Ahmed

26-year-old Jamil fled his home in Myanmar four days after Eid, in September 2017. He ran away, like the rest of the villagers, after seeing the fires lit by the Myanmar military advancing. They ran into the forest and hid. The military saw them escape to the forest and opened fire. Many of the villagers were struck by the bullets and died. A bullet struck Jamil in the hand, which has left him disabled.

When the villagers felt it was safe enough to move, they began the trek towards Bangladesh. Crossing into Bangladesh they left behind the violence and oppression they faced in Myanmar, but the memories still haunt thousands of the refugees. “I often wonder when I will be able to return to Myanmar. I do not feel peaceful when it think about it. If Allah wishes us to go back we will; if not, we will stay here.”

Like many Rohingya refugees, Jamil expresses his mental health issues by describing physical symptoms. “When I am not peaceful, I feel like I’m getting thinner. When I came here I lost weight and I lost my energy.” He desperately misses his home but knows what would happen if he were to return: “I do not feel peaceful when I think of going back home. When I think of my home, I feel like flying there. But if I go there [now], it will be killing myself. In my heart, I still have love for my land. One day I will definitely go back.”

Mabia Khatun

Mabia, 40 years old, fled from Myanmar to Bangladesh in November 2017. “I was feeling unhappy in Myanmar because Myanmar’s police were cutting our heads off, imprisoning our children and killing us.” The violence directly affected her family: “In the morning I heard the news that my brother and sister had been killed. I went to see. Everywhere in the house there was blood.” They had been decapitated.

Now in Cox’s Bazar, “I feel happy in the camp because I can sleep at night without any problems - in Myanmar we slept during the day and not at night, because the police would take our neighbours and family members at night. I will never forget what happened in Myanmar. Sometimes it comes back to me. I feel unhappy when I think about it. I can’t sleep and I have body pains. I get dizzy when I think about it.”

Mabia’s children have likewise been affected: “I have small children. When my mother tells the children that we will one day return to Burma [Myanmar], the children say ‘no, if we go back, the military will kill us.’ They are afraid to go back."

Yasamin Akter

Five-year-old Yasamin fled with her mother, 25-year-old Fatima Khatun, and four-month-old brother, Tawhid Uddin. They left their village because, as Fatima says, “the military people were torturing people.” She says her husband was enslaved, the mosques and madrassas closed down, people were not allowed to get married and “the pretty women and girls were raped in front of parents and brothers. I’ve been witnessing our lack of freedom since I was a teenager.”

The family fled when the military started burning houses in their village. When the fire reached their house, Yasamin was still inside. Fatima rushed to her when she heard her screaming. She saved her from the flames but not before her leg and buttocks were badly burnt. They have settled in the refugee camp in Bangladesh but life is not easy: “Here there is no peace as we don’t have our own land, our own people, and our country,” says Fatima.

The loss they have suffered haunts Fatima. What particularly worries her, in a culture where a women must get married, is the difficult future her daughter will face: “A few days back I lost consciousness thinking about what happened. They destroyed her life — if it was a son I could get over that, but because she’s a girl, they have destroyed her life. We don’t have any money or land and somehow we need to get our daughter married.”

Asmot Ullah

“The Myanmar government were killing people in front of us, so to save our lives we came here,” says 23-year-old Asmot, who fled his home in Rakhine on 25 August 2017.

He recalls the night of the attack: “The Myanmar government surrounded our village and started shooting.” All of the villagers started running. The soldiers turned their machine guns on those fleeing: “My brother was shot dead by the Myanmar government in front of me… we were running together. He was behind me. He was shot in the belly. He fell. Then I was shot in the thigh. I fell. From the ground I saw that my brother was dead. Then someone took me on his shoulder into the jungle.”

For seven days, a group of the villagers hid in the jungle without food or shelter. Through the rain and mud they made it to Bangladesh. “I miss a lot my brother, all the time,” says Asmot. “I’m thinking about him and I feel very unhappy. I’m thinking about my brother day and night. When I think about him, I do not feel peaceful. Sometimes I remember what happened in Myanmar in my dreams.”

Jahangir and Badarul

15-year-old Jahangir with his 50-year-old uncle Badarul Hoque. Badarul lives with an undiagnosed mental health condition and needs family support to get by. They came to Bangladesh one day before Eid.

“Military people were torturing and killing, that’s why we came," 15-year-old Jahangir explains. "I didn’t see [the killing] myself, but I saw body parts in the river: heads, hands, legs.” Jahangir says that his community knew of the violence being perpetrated nearby so they gathered and left for Bangladesh. His father would not leave until he had checked on his sister who was in another village. He left and never returned. “I still don’t know where my father is, if he is alive or dead.”

While the entire family always cared for Badarul, the bulk of responsibility fell on Jahangir after his father went missing. He describes his uncle's condition: “Sometimes, at night, my uncle shouts a lot. His condition was a little better before, but it became worse here [in the camp]. It became worse because he heard shooting and bomb blasts.”

Life is hard in the camp. While their immediate everyday needs are taken care of, they are suffering. When asked what Jahangir does to make himself feel better he says: “Why would we feel good? We left our land. We left our house. Now we’re living in small tents. There is nothing to feel good about living here. My family members say that whenever they remember what happened in Myanmar, they don’t want to go back there. But when they see the little tents they’re living in, they want to go back. What can we do here, we can’t do anything.”

Mohammad and Osman Yunis

Mohammad and his six-year-old son, Osman, arrived in Bangladesh at the end of 2017. “We came here because the Mogh people [derogatory term for local Rakhine Buddhists] were shooting and burning people. My uncle and two cousins were shot and killed in front of me.” Mohammad also describes how he saw his parents being beaten up.

The trauma of the violence, coupled with finding himself a refugee, has taken a toll: “I’m not feeling well here. My brain has become out of control.” Mohammad also describes the physical manifestation of his mental illness: “I used to be fat. I’m getting thinner and thinner day by day thinking about what happened.” He went to MSF for help: “I could not sleep because I used to roam around, not sleeping and hitting people. So I started taking medicines and they help me.”

Comparing life in the camp with life in Myanmar, Mohammad says: “Living in a camp - I don’t want to - it’s not a good environment. We had good land, a good house. I’d be very happy if I could go back there. But the Burmese people burnt my land and house.”

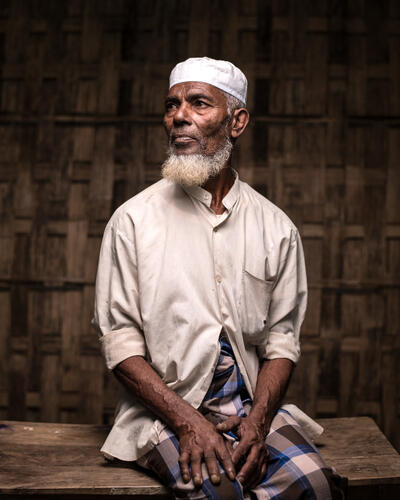

Noor Alom

70-year-old Noor Alom was a rice farmer in Myanmar before he fled to Bangladesh on 30 August 2017. He describes the attack on his village: “People were being burned; they were burning them in their houses. The people in my village started running, so I ran too.”

All six members of his family escaped physical harm, but the attack, coupled with the loss of all his worldly possessions, source of income, and his new identity as a refugee, has taken a psychological toll. “My head started hurting after I arrived here,” he says, describing what doctors commonly diagnose as physical manifestations of mental illness.

“I was happy with my family [in Myanmar]. Now that I cannot support them or move freely, nothing makes us happy. If we were home we could celebrate [the Muslim festival of] Eid. But we can’t do that here, we just sit and wait.”

Rohima Khatun

“We came to Bangladesh because the Mogh [derogatory term for local Rakhine Buddhists] were torturing us. They told us that we had no right to stay in Myanmar, and we should go back to Bangladesh,” explains Rohima, a 25-year-old Rohingya refugee, who fled her Rakhine village and arrived in Bangladesh in September 2017.

“First the military called a meeting. Those people who stay in their houses will be okay, they said, but those who move from place to place will be arrested. At 4am the next morning they came back and surrounded the village. They separated the men and women. They handcuffed the men and started raping the young girls. The men were shouting and so were the children. They started beating them.”

They set fire to the houses. Military men went to rape her she said, but when they saw she was seven months pregnant and carrying a four-year old child they left her. The child was terrified and started screaming: “The four-year-old was crying so they took the child from me and threw him in the fire. They also shot my husband in front of me in the yard of our house.” She discusses life now, a year later: “Every single moment I remember this and get emotional because I lost my neighbours, husband, child, relatives.”

Since August 2017, MSF has conducted over 16,000 individual mental health consultations and 18,000 group mental health sessions among Rohingya refugees living in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar district. All MSF health facilities provide mental health services, and both psychological and psychiatric services are available at all inpatient facilities and some primary health centres.

Refugees experience flashbacks, generalised anxiety, panic attacks, recurring nightmares and insomnia, as well as illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression. MSF is also seeing chronic mental health difficulties and psychiatric needs within both the host and refugee communities.

MSF is one of very few organisations providing such services to both Rohingya and Bangladeshi patients in Cox’s Bazar district. The limited availability of mental health services and particularly more advanced mental health services, including psychiatric care, in the area remains concerning.