It's late Friday afternoon in the community of Boitekong, on South Africa’s platinum belt, northwest of the capital Pretoria and the main city of Johannesburg: the bare-earth streets are busy with off-duty mineworkers in multi-coloured overalls. In yards and on street corners men work on television sets and car engines, their end-of-week beer quarts in hand. A group of men on the plot of an auto-repair business invites two female employees from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to sit a while. They are community health workers (CHWs) – daily walkers of these streets, who have been raising awareness about the serious potential health consequences of sexual violence, and how related illness can be prevented or reduced with timely access to proper healthcare. The women hand the men several information cards, and two condom packs – yellow and pink, banana and strawberry.

“Often when a woman says she is raped, it isn’t actually rape,” says the owner of the yard, a mechanic. “A woman might sleep with a man, and then say ‘pay me R5,000 (€310), or I will lay a charge of rape’.”

The mechanic’s attempt to cast men as victims is immediately undermined when his friends wolf whistle at a woman strolling hand in hand with her partner on the road. Her clothes are not especially revealing but the mechanic still says, “I’m telling you, in five years the women here will be walking naked in the streets.”

A common occurrence

The health workers have heard enough, and get up to leave. Acts of sexual violence are shockingly common in platinum belt communities, and no amount of ‘victim shaming’ will change the fact that the perpetrators are almost all men, and that the ones enduring terrible suffering as a result of rape are, overwhelmingly, women. To give some sense of the scale of the crisis: in 2015, MSF conducted a survey around Rustenburg, where Boitekong lies, and found that one in two women between the ages of 18-49 had experienced some form of sexual violence, while one in four women had been raped in their lifetime.

“There is also a lot of anger and frustration, because living conditions are harsh - many men and women are living in mkhukhus [tin shacks] next to the mines”, says Lydia Ganda, one of the health workers. “Community structure is lacking in these places because most who live here are migrants from other parts of South Africa, or other African countries. They come to find work on the mines but many find nothing, especially the women who end up depending on the men for their economic survival. People drink heavily, but of course there can be no excuse for rape.”

Dineo Lekone* was raped by a male acquaintance on the night of her birthday in September 2016.

“We had been drinking in a club with my girlfriend and some friends. When my girlfriend disappeared, my male friend offered to take me to a petrol station to buy airtime so that I could call her,” Lekone recalls.

Instead of returning her to the club, Lekone’s male friend drove to his apartment, where he threatened to kill Lekone and throw her body in the Crocodile River, unless she “let him do whatever he wanted to me”.

Underreported and poor awareness of support

Of the approximately 11,000 women and girls that are raped in Rustenburg and the surrounds every year, only five percent reports the assault to a health facility, despite the fact that HIV and other sexually transmitted infections are potential consequences of rape, as are depressive disorders and unwanted pregnancies. Stigma is partly to blame – the mechanic and his friends are representative of a terrible societal tendency to lay the blame for rape at the feet of victims. Poor awareness of available treatment compounds the problem, with MSF finding that one in two women does not know that HIV is preventable after rape.

Even if more women did know, the fact remains that essential services for survivors of sexual violence are sorely lacking. According to a recent MSF report, three-quarters of South African public health facilities that have been designated to provide services to rape survivors are unable to provide comprehensive care.

Constance Phiri* struggled to find care after being gang-raped by three house intruders in May 2015. She was taken by police to the nearest Community Health Centre, only to discover that “the clinic had no forensic nurse and no sexual assault kits”. Phiri had to be transported to Brits Hospital nearly an hour away, where she was able to access the medical and clinical forensic services she needed.

“I went back for counselling and after three sessions I found I was strong”, she says. “A lot of women do not go to a properly equipped facility after being raped because they don’t see any mark on their body, but I would be dead today if it wasn’t for the counselling I received - I would’ve killed myself. We need to be able to get these services as women, and we need to use them.”

Threading strands of support in local communities

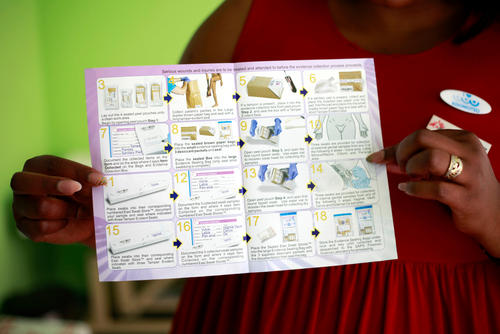

MSF has been working since 2015 to capacitate several designated public health facilities in the platinum belt as ‘Kgomotso Care Centres’, providing a comprehensive package of medical services (including clinical forensic services), as well as psychological and social services to survivors of sexual violence. For a long period, however, the numbers of clients entering the ‘KCCs’ remained lower than expected – stigma and low levels of treatment literacy being the likely culprits.

To link a greater number of people to care MSF raises awareness in communities, on the one hand, and on the other screens people in a variety of contexts. Health care workers like Ganda work in platinum belt settlements daily, alerting people to the importance of care for survivors of sexual violence. In November 2017 a social media marketing campaign was launched targeting multiple audiences with tailored messages about the nature and availability of KCC services. MSF has begun screening for sexual violence in police stations and grassroots welfare organisations, where many rape survivors are known to report, and linking survivors of sexual violence to the services they need. This strategy of threading strands of support through platinum belt communities appears to be working - referral numbers from community institutions are rising, and with the light fading fast in the community of Boitekong, the MSF health workers are repeatedly held in conversation at gate posts as they make their way to their driver.

“It has taken two years but we are really welcomed here now. More survivors than ever before are hearing our messages and accessing care,” says Ganda, although she is quick to add that it will be a long time before the prevalence of rape begins to fall.

“For that, bigger social changes need to happen and government, NGOs, civil society, grass roots organisations, and other community structures will all have to come together and cooperate closely for a long period of time,” she says.

About MSF’s response to sexual violence: In South Africa, the 42,496 rape cases reported by the South African Police Services for 2015/2016 are estimated to be only 4-11 per cent of the true number of rapes. An MSF study from 2015 found that on South Africa’s platinum belt, one in four women is raped in her lifetime yet only 1 in 20 ever report to a health facility for treatment. MSF has been working with the North West Provincial Department of Health since 2015 to capacitate designated facilities as ‘Kgomotso Care Centres’ (KCC), providing a complete essential package of medical and clinical forensic services to survivors of sexual violence. Currently, MSF supports staff in three KCCs - all in primary care settings – to create a comforting environment for survivors, offer survivors the services that meet their needs, or refer them to the services of other government departments.