All Speaking Out Case Studies > MSF and the Rohingya 1992-2014

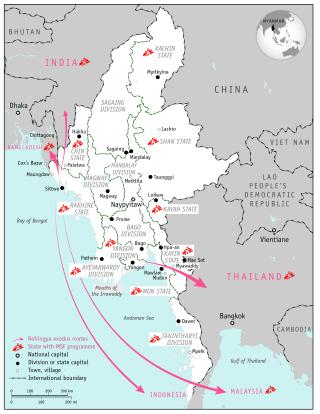

The Rohingya people live in northern Rakhine state (formerly Arakan), located in western coastal Union of Myanmar (formerly Union of Burma) bordering Bangladesh to the north. The stateless Rohingya are predominately a Muslim minority, in a majority-Buddhist country. Since the late 70s, the Rohingya have fled persecution and violence to seek refuge in Bangladesh.

The case study "MSF and the Rohingya 1992 - 2014" brings to light two decades of MSF advocacy activities as part of its humanitarian assistance to the Rohingya people in Bangladesh and Myanmar and explores the questions and dilemmas the organisation was confronted with surrounding speaking out.

Questions and dilemmas:

- Under an authoritarian regime, should MSF maintain a medical operational presence which enables information collection for potential public positioning, while imposing a communication silence for fear of losing access? Two apparent choices regarding public health and "temoignage" emerge:

- Abandon patients whose life depends on MSF treatment, such as HIV/AIDS cohorts, to speak out against the persecution of a population such as the Rohingya.

- Abandon a persecuted population through silence, or no public witness of their plight despite the maintenance of an operational presence and data collection which attests to the suffering.

- While substituting MSF public witnessing with second-hand witnessing (MSF gives data to human rights organisations, UN agencies, media, etc.) in order to maintain contact and medical activities for the Rohingya population in danger:

- Is it possible for MSF to control these second-hand messages? What should MSF do when the message is altered or simply ignored?

- What is the value in substituting MSF's public voice with that of non-medical organisations?

- What is the value in maintaining a presence when the substituted voices are not impacting the plight of the Rohingya?

- When purely medical data are not available or the data available do not directly link health status to persecution, should MSF denounce persecution on the basis of data which describes human rights violations?

- Does this risk the organisation's credibility as medical and humanitarian? If so, should MSF remain publicly silent to maintain credibility and/or access? Are there cases where silence increases access over time?

- If MSF credibility is not at stake and no direct link between the health status and persecution can be established, what other circumstances could/can justify an MSF refrain from denouncing human rights violations?

- When MSF agrees to work concurrently in "ethnically exclusive" clinics to prove its impartiality, such as those clinics for the vulnerable Rohingya separated from those from the larger Rakhine population, is MSF thereby complicit in segregation policies? In so doing, does MSF reinforce the regime's policies of ethnic detention and "encampment" ?

- How far can MSF push negotiations for access with a regime that detains MSF staff members?