1978 : The Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh (In French)

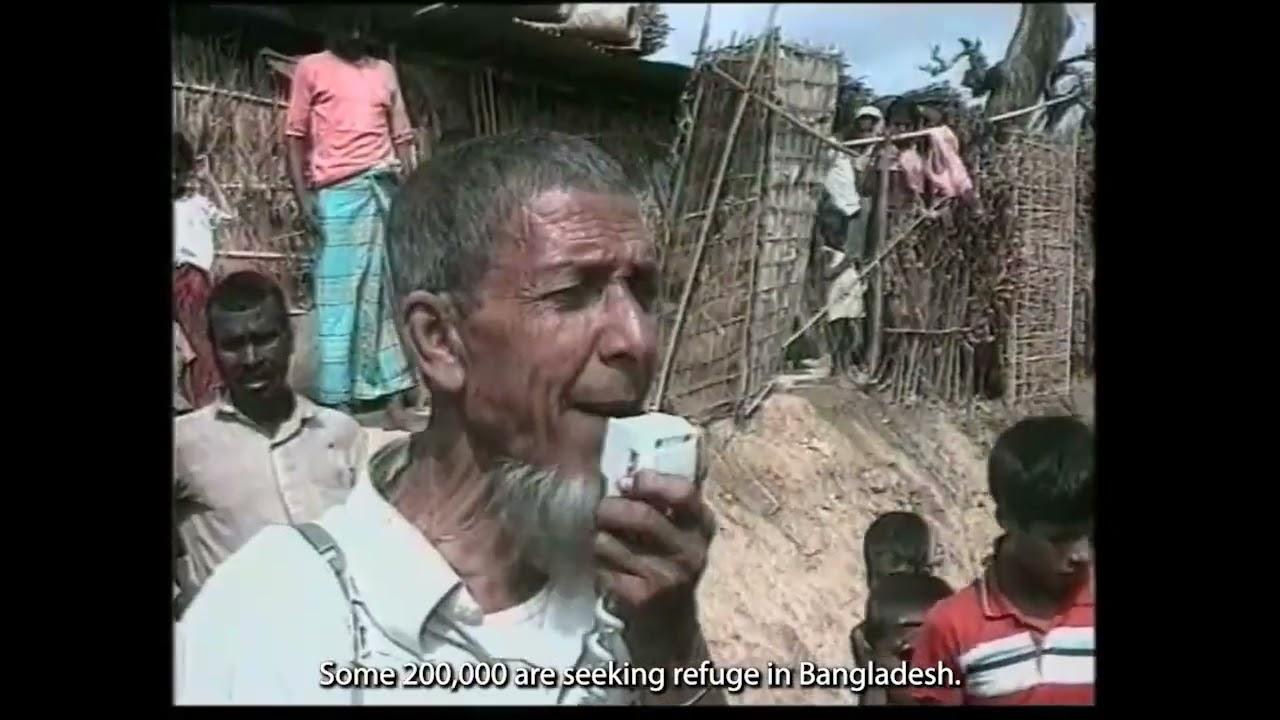

Report from Bangladesh in the refugee camps of the Rohingya Muslim minority, driven out of Burma since last February by the Burmese authorities as part of the ethnic cleansing operation named “Dragon”.

1978 : Les réfugiés Rohingyas au Bangladesh | Archive INA

MSF: 1992 a year in focus (in French)

More than 200,000 Rohingya arrived in Bangladesh fleeing violent persecution in Myanmar.

MSF: 1992 a year in focus (in French)

Cyclone batters Myanmar's main city Yangon

Report on cycle Nargis devastating most of Burma

Cyclone batters Myanmar's main city Yangon

Cyclone Nargis Underscores Challenges in Delivering Aid

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis devastated much of Burma. It also demonstrated the weakness of the international community in trying to deal with the country. For weeks, the military government blocked efforts to help more than two million survivors of the storm.

Cyclone Nargis Underscores Challenges in Delivering Aid

Medecins Sans Frontieres presser on Myanmar aid efforts

MSF Press Conference

Medecins Sans Frontieres presser on Myanmar aid efforts

Bangladesh seeks end to Rohingya aid

Rohingya refugees in neighbouring Bangladesh are living in conditions described by Medecins Sans Frontieres/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) as catastrophic. Some 300,000 Muslim Rohingya refugees fleeing violence in Myanmar live here without food or clean water. The UN human rights envoy to Myanmar has called for an independent investigation into the recent violence in Rakhine state. But the Bangladeshi government has told three aid agencies including MSF to stop helping them.

Bangladesh seeks end to Rohingya aid

Claims of ethnic violence in Burma

Human rights campaigners have accused the Burmese authorities of presiding over ethnic cleansing attacks on minority Rohingya Muslims. New footage has emerged of Buddhist attacks on Muslim homes and shops.

Claims of ethnic violence in Burma

Aung San Suu Kyi on the Rohingya Muslims

Aung San Suu Kyi explains her view on the violence committed against the Rohingya Muslim community of Myanmar. Footage shot at the Japan National Press Club in Tokyo.

Aung San Suu Kyi on the Rohingya Muslims

Analysis: Myanmar’s conflicting narratives

aljazeera.comRakhine Peoples Protest Against MSF

Protests against MSF in 2014

Rakhine Peoples Protest Against MSF

Rohingya exodus: Thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled Myanmar

Rohingya exodus: Thousands of Rohingya Muslims have fled Myanmar

Rohingya crisis: they killed my beloved son in front of me

Testimony from Rohingya refugee Rashida who fled Myanmar when her village was attacked by Myanmar security forces.

Rohingya crisis: they killed my beloved son in front of me

MSF: Myanmar army killed some 7,000 Rohingya in a month

A medical aid group estimates at least 9,000 Rohingya civilians died in Myanmar in just one month earlier this year, almost 7,000 of whom were killed in violent attacks by troops.

MSF: Myanmar army killed some 7,000 Rohingya in a month

Bangladesh/Myanmar situation: Statement of the ICC Prosecutor

Statement of the International Criminal Court (ICC)