Unlike some other humanitarian emergencies where local healthcare systems collapse or struggle to meet people’s needs, hospitals and civil society organisations in Ukraine continue to function in the ongoing war in the country. Since hands-on medical care is largely taken care of, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams are currently focusing on building a network of support to hospitals and first responders, mostly through training and donations.

Here we share a window into an MSF team’s two-day visit in late May offering support to people in a rural town in central Ukraine.

Day 1

A mobile team en route

At 7.30 am there is a rush at the entrance of a hotel in Kropyvnytskyi, a city in central Ukraine 150 kilometres from the nearest frontline. MSF set up a small base there in April. People load some medical and logistics materials into three cars, and the project coordinator does the last briefings on the situation and planned activities with the mobile team members as they get ready to leave.

Fourteen people, including doctors, psychologists, translators, logisticians and drivers, head to Holovanivsk, a small town of 16,500 inhabitants, located two and a half hours west by road. The convoy crosses vast and mostly empty fields for soya, corn, wheat and sunflowers, as the crops have not yet grown. The cloudy blue sky and the yellow soya flowers recreate the bi-coloured Ukrainian flag.

Division in groups according to tasks

At 11 am the MSF team reaches Holovanivsk. Over 1,000 people displaced by the war are registered in the town, but they live scattered, the majority in nearby villages.

The team is divided in four groups. Olexander and Juan Pablo, doctors from Mariupol and Argentina, go to the local hospital and ambulance centre. In each location, they will carry out training sessions about mass casualty response and decontamination; in other words, on how to triage during a situation of a high influx of wounded patients and on how to proceed in case of an attack with non-conventional weapons.

Two Ukrainian psychologists, Olha and Alissa, go to assess the condition of people in the displaced communities. They would like to offer individual mental health consultations and try to arrange a psychotherapy group. The war is having a huge psychological impact and many people suffer from symptoms like intense fear, constant stress, persistent worry, hopelessness and panic attacks.

The midwife, Florencia, and the mental health activity manager, Ariadna, from Argentina and Mexico, accompanied by the translator Olha, head to a school to launch a two-day workshop on sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). In the meantime, the Brazilian logistician Tanain and other staff visit the humanitarian centre to donate relief items.

Addressing needs of people who are displaced

Olena waits at the humanitarian centre. A former teacher in chemistry and biology, Olena is currently the village council secretary.

“During the first days of war, 150 to 180 people arrived here daily, mostly at night,” says Olena, “Many were transiting to other places.”

“It was awful… nobody was prepared, so we organised ourselves to do different tasks: to cook, clean… Everyone brought things,” continues Olena. “As women with small babies couldn’t stay in the social centres, some locals offered their homes. There was a lot of solidarity; I have never seen anything like this.”

Olena’s own son and partner used to live in Kyiv, but they moved here also shortly after the war started.

Interview with Olena Myroshnychenko, Holovanivsk Council Secretary

“It is now very important to get humanitarian assistance,” says Olena. “We can temporarily ask farmers to provide food, but other things like hygienic items are helpful… people are running out of money, they have already spent a lot.”

An MSF team was in Holovanivsk two weeks earlier, so before this visit the local authorities had identified the needs: blankets, towels, bedding, solar torches and pillow covers.

Victimisation and barriers for survivors of sexual violence

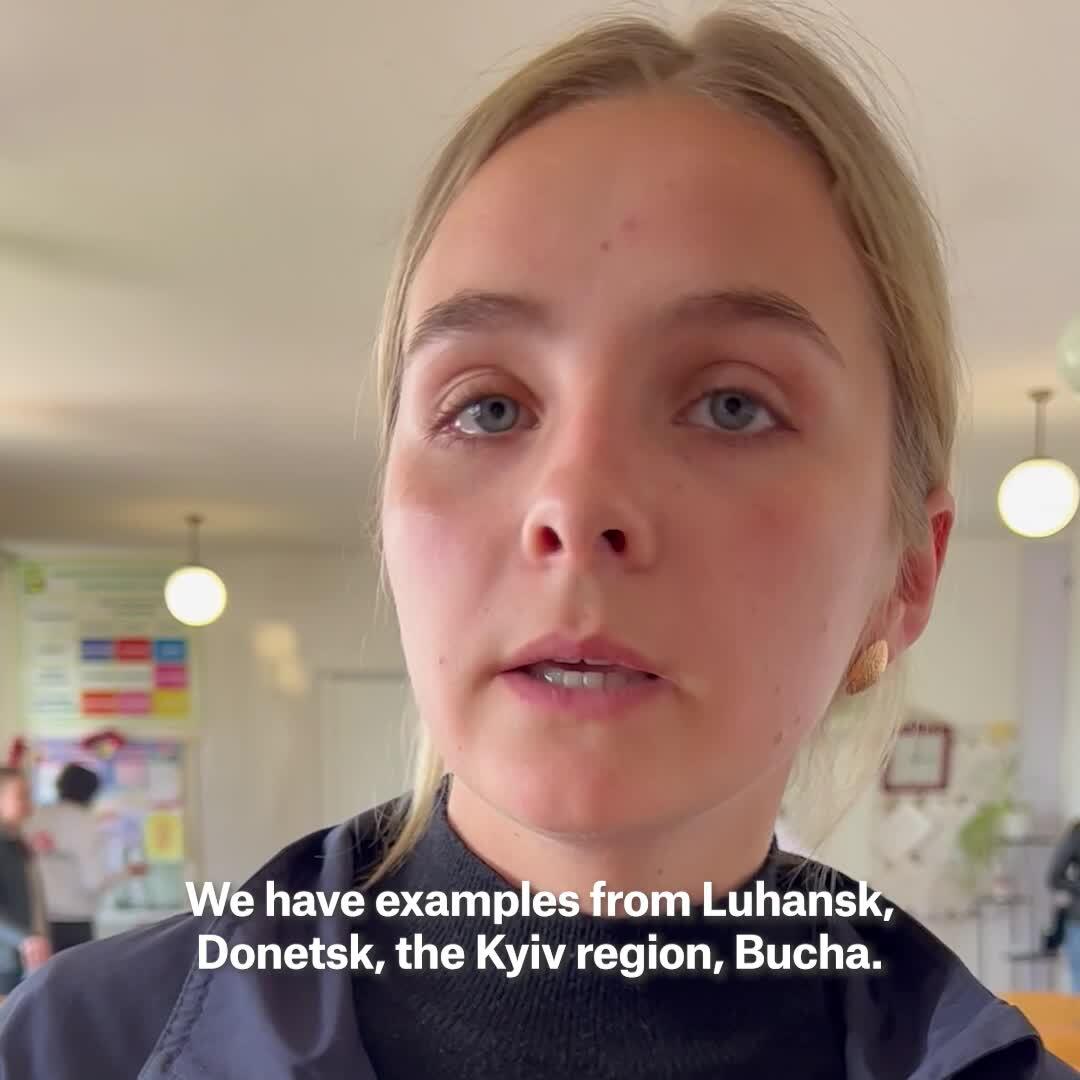

Not far away, around 35 healthcare workers, social workers, teachers and psychologists, all of them women, participate in the training on SGBV. The facilitators talk about the feeling of victimisation some women can have after giving birth to a child as a result of a rape, or about the barriers male survivors experience.

“It doesn’t matter what you wear, you don’t have a sign to be raped,” midwife Florencia says in the session to the group. “It is always the guilt of the perpetrator.”

“The training is very useful and informative,” says Olga, a psychologist at the school. “It’s extremely important in these times because we often encounter cases of violence. We have examples from Luhansk, Donetsk, Kyiv region, Bucha... We want as many people as possible to be aware of such cases.”

Day 2

Understanding survivors’ bureaucratic challenges

The next day, the group starts with a role-playing game. Each participant takes a different role: a police officer, a doctor, a psychologist. The woman portraying a survivor holds a string and moves from one person to the other seeking assistance.

By doing this, she creates a complex spider web out of string. The web represents the bureaucratic hurdles survivors find in real life. The solution? To create a single pathway with all the services, including medical treatment and psychological assistance, something MSF is trying to support health authorities with in parts of Ukraine.

"Our aim is to sensitize these first line responders in order to increase the number of people reaching the services,” says Florencia. “But it is proving hard.”

Sexual violence assistance training in Ukraine

Violence has put people in vulnerable situations

In another room of the school, the MSF psychologists carry out psychological support sessions with adults and their children displaced by the conflict. Maryna and Olena come from the Donetsk region and arrived here one and two months ago, respectively. They live in an empty house in a village near Holovanivsk with another woman; all of them have children between six and 12 years of age.

“A relative living here [in Holovanivsk] was told by administration officials about the place where we are now,” says Olena. “When we first arrived, we were afraid about how people would react. We didn’t want them to feel sorry for us. But the attitude was very good, people have been very warm.”

Both are entrepreneurs. Before the war, Maryna had a beauty parlour and Olena ran a small store. Now they are helping in a local kitchen to prepare food and grow some vegetables.

Sandra also shares her experience on the effects of the war. She is in the last year of her bachelor studies on international management and comes from Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second biggest city.

“I feel okay, in general. I am alive, and my parents and husband are with me,” says Sandra. “We married here just one month ago. But I can’t read the news. It takes me just one minute to get frustrated, to start crying… I still can’t believe this is possible.”

She tries her best to occupy her mind with tasks, be it drawing or writing poems. She says some of her friends chose to stay in Kharkiv, despite the extremely hard situation – one girlfriend who has a small daughter is living in a partially destroyed home.

“I don’t miss any material belongings,” says Sandra, “but I miss my city, the trees, the buildings. I would like to just get back home.”

But then she recalls why they fled.

“It was very stressful. I couldn’t cope with it. I felt nauseous just by looking at food,” continues Sandra. “During the first days we always moved to the bunker. Later when the bombs fell, we went to the bathroom and covered our heads with pillows and blankets. We sat down squatting and prayed.”

“Jet fighters flew over the building,” she says. “The sound of the bombs was so loud, every time it seemed they were hitting us.”

Building preparedness at the hospital

At the hospital, the MSF medical team concludes the training; Yanina and Oleksii sit again in their paediatric department office dressed in white coats. They studied medicine together. She is from Zaporizhzhia and he is from Melitopol, in the southeast, but both moved to Holovanivsk two years ago.

“We have had fewer patients since 24 February [start of the war] but they come with more severe conditions,” says Yanina. “A lot of people from the region have left Ukraine and many people who are displaced within the region don’t know exactly what we do.”

The wall is full of drawings, done by children who have received medical support. The patients draw about their experiences with health issues. A cat, for example, was drawn by a girl who had asthma.

“In the first month of the war we worked at night and the surgical team was 24 hours on standby,” says Yanina. “During the siren alerts, we went to the bunker with the patients. These days we stay in the safe area of the corridor.”

“We have received humanitarian assistance over the last months. The training is important in rural areas for the staff to develop knowledge, not to panic and to know how to act step by step,” she continues. “We have had children from occupied territories, like a boy from Mariupol. He developed allergic rhinitis [inflammation of the lining of the nose] from spending one month in the bunker and was in a bad psychological condition.”

Things are not easy for the doctors themselves either. They check every day on their own families.

“I try to avoid thinking much, the easiest is to just come to work,” says Oleksii. “I still have so many relatives in Melitopol. My parents live near the military airport and keep hearing military planes. People trying to leave Melitopol to other parts of Ukraine spend days in each checkpoint.”

During the conversation, the siren alert sounds on everyone’s mobile phones. It is the third time today. The previous two were in the middle of the night. In town, the different members of the MSF team regroup. They eat lunch, wrap up their work and get into the three cars to travel back to Kropyvnytskyi. The two-day visit to support people in Holovanisk has come to an end.