Eighty-three thousand people have disappeared over 50 years of war in Colombia, at the hands of guerrillas, paramilitaries, criminal groups and state forces.

They vanished leaving a void that their relatives fill with guesswork, wishes, frustration, doubts, uncertainty, anxiety, despair and depression. Eighty-three thousand families don’t know when they will be able to mourn their relatives, because they don’t know what happened to them: their grief is suspended.

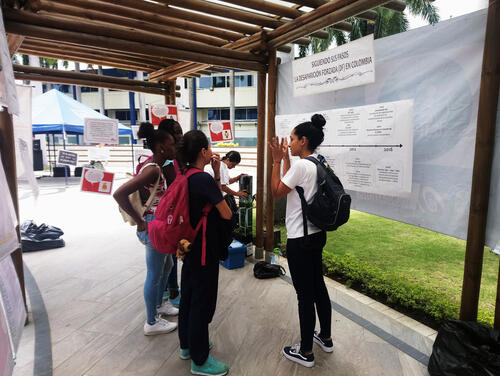

On 30 August 2018, the victims of forced disappearence are remembered by the International Day of the Disappeared.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been working in Puerto Asís and Cali, in Colombia, for a year now, providing psychological assistance and support to families of the missing.

We spoke to Giulia Panseri, MSF’s project coordinator in Puerto Asís and Cali, about the services we run, and the difficulties people are facing.

We are talking about a crime against humanity in every sense.Giulia Panseri, MSF project coordinator in Puerto Asís and Cali, Colombia

What do the 83,000 missing people in Colombia represent?

The missing people represent a wound which must be healed. But it's a wound that keeps opening, because it's still happening. We’ve spoken to patients who have lost loved ones just six months or a year ago. They aren’t the majority, but they keep coming to receive our services.

The damage is huge: not knowing what happened to their missing family member causes people tremendous pain. Not knowing the truth, not knowing their whereabouts, not being certain. It’s a form of suspended grief; they can’t mourn their loved ones because there’s no closure. And the not knowing continues – month after month, year after year.

Silence increases their pain: people are still afraid to talk about what happened to their brother, father, cousin or daughter. The families of the disappeared are also stigmatised. People look at them as if to say, “if that person was taken, it must have been for a reason."

Public institutions need to do more to stop this kind of stigma, and bring justice to families of the missing. And that's where there is still a lot left to do. We are talking about a crime against humanity in every sense.

What have public institutions done in response?

There is still a lot that needs to be done. At present, there are 3,000 recovered bodies that have yet to be released to their families. But there’s a lack of resources and effort. The Missing Persons Search Unit has been created, but it needs resources, budgets, and deadlines to carry out its mission successfully.

We don’t know how the new government will approach this issue. We also don’t know what will happen to the signed peace agreements, which could be a source of information on the whereabouts of missing people. We have to wait to see what the new administration's next steps will be.

What is a good day for MSF teams like?

Our project is one of a kind. It’s not like a medical intervention for physical diseases such as malaria, where someone recovers after hours or days of illness: mental healthcare requires time.

But, of course, a good day is when you ‘close’ a case; when, despite the fact that they have not recovered their loved one, the patient can continue with their life. The symptoms that gripped them – the sadness, anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and irritability they felt – disappear, or they have the tools to combat them.

We provide a comprehensive care package and our teams support patients with every step of their recovery process. They are also helped in the search for their loved one or in getting legal advice and rehabilitation.

Seeing someone finally recover; that is a good day.

How many patients has MSF cared for?

In total, 297 people have received mental heath services from our teams. In the last six months alone, we have seen 203 patients. These numbers increase as awareness about MSF grows.

We have to keep in mind that Cali is a big city, the third biggest in the country, and it’s hard to raise awareness about our services. In Puerto Asís, it’s different because it’s smaller.

In the rural areas, the difficulty is the distance and how people in need are able to reach our services. If we find several families who need our help, or are sent a referral from another organisation we work with, we travel to them rather than trying to get them to come to us. It is a model of care that we want to promote.

But many people still believe they must keep silent due to stigma, uncertainty about the future, or distrust and fear. Some people have received threats or been extorted for money when they’ve tried to find out about their missing family members. There is still much to be done.

Is there any patient that you remember in particular?

I remember one patient who didn’t want to receive mental healthcare any more because she didn’t think it could help her. At some point a psychologist from another organisation had told her that she had to live with her grief. She asked herself, “grief of what?”. She had nobody, she had no explanation of where her loved one was.

She later knew about MSF services and came to us. With our staff, she started to recover emotionally. As well as psychological care, we put her in contact with other organisations for relatives of the disappeared that offer legal advice, professional workshops, and other social services.

We have to understand that psychological care alone doesn’t resolve the situation. Knowing that you are not alone and working with others who are in the same situation is also really helpful for people’s recovery.

A disappearance often affects the family economy, so the consequences of a disappearance are multiple and need to be tackled with an all-round approach. MSF’s work here must be as comprehensive as possible, and be coordinated with other organisations that respond to needs that we do not directly address.

In Colombia, MSF works in the cities of Tumaco and Buenaventura supporting victims of violence with mental health services, and provides comprehensive care to survivors of sexual violence, including voluntary termination of pregnancy.

In Cali and Puerto Asís, we offer psychological support to the families of victims of forced disappearance.

We also have an emergency response team that monitors the health and humanitarian situation in the country.