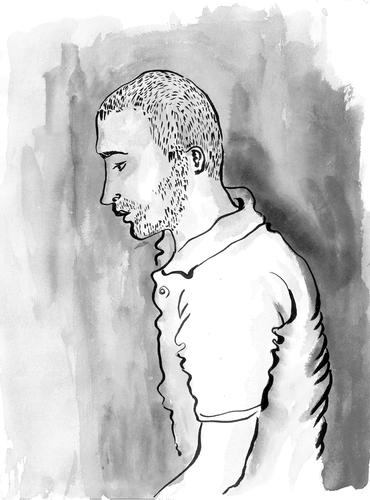

On his way to meet friends for coffee, 27-year-old computer repairman Abu Ahmed was injured by a cluster bomb. Four weeks later, his bone fracture has failed to heal. His only hope is specialist orthopaedic surgery in Turkey – but he is trapped in east Aleppo. Bedridden, he now watches in despair as his neighbourhood falls into rubbles after the new wave of airstrikes.

One month ago I was meeting friends for coffee, as I do every morning. My friends were late so, when the raid happened, I was the only one there. Standing next to my neighbour’s house, I heard the missile coming towards me, though I didn’t see it. I sprinted towards a nearby building, but I wasn’t fast enough.

It was a cluster bomb. Some of the bombs exploded, hitting the surrounding buildings with force. A piece of shrapnel pierced my left leg. Other than that, I just had surface wounds.

Lying on the ground in shock, I felt I’d lost part of my body. Neighbours started to gather around me, but no one had the courage to approach – they were afraid of the unexploded bombs lying all around. They were also afraid of a second raid following on from the first – that’s how it’s done – so they waited for five minutes until they were sure that the plane had gone.

They tried to lift me. I was in such pain I could only shout. They called an ambulance, and fortunately the ambulance arrived. The hospital is nearby – the journey should only take a couple of minutes, but that day the driver had to take a different route, as many roads were blocked by debris and bodies from the raid.

At the hospital, they X-rayed my leg, and then took me to the operating theatre. The blast had dislocated my leg and shattered my thighbone into lots of pieces. I asked if they would need to amputate, but the doctor said no.

Afterwards, I was taken to a room on the first or second floor. It was very small and had been damaged by airstrikes, so there were no shutters or glass in the windows, and people were constantly going in and out.

In a room like that, you wait in constant fear that you’ll be targeted. Through the open windows, I could hear the warplanes circling. After an hour, I couldn’t take the stress any longer, so I asked to be taken home.

When I arrived home, it was dark. My neighbours came out of their houses and carried me up to my room on the first floor and laid me on my bed.

I tried to get some rest, but it was impossible. I could still hear the planes and the missiles exploding around us – that night the raids didn’t stop at all.

The hospital had prescribed me some medications – antibiotics and painkillers – but they made no difference.

After seven days I should have been feeling better, but the pain had got to the point where I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t get to hospital, because there were no ambulances, and once I got there, there’d be no guarantee I could get to see a doctor.

I started to think about how I could speed my recovery in other ways. On the advice of friends who are nurses, as well as old people who know about traditional remedies, I started to ask around for milk and honey. I don’t have the money for these things, but I was willing to take out a loan. But it was almost impossible to find any.

Every so often, some good people from my neighbourhood brought me a chicken or an egg – under the siege, everyone raises one or two chickens at home.

After 16 days, my thigh had started to swell up. It was too painful to touch – I couldn’t even cover it with a blanket.

Finding a vehicle to take me to the hospital was hell. There are few private cars running because of the petrol shortages. In the end, I called for an ambulance, telling them, “I’ll crawl to the hospital if I have to”. I got there eventually and stayed put until the doctor showed up.

The doctor sent me for another X-ray, then told me to come back in a month.

A friend sent my X-rays to an orthopaedic surgeon he knew outside east Aleppo. He came back with bad news: the operation had been unsuccessful and I needed to be operated on all over again. The chance of them being able to do it here was minuscule. What I needed, he said, was specialist surgery across the border in Turkey.

When I heard this, my morale sunk so low that I lost my appetite. For a whole month, I had lain in bed, not moving, to let my bones heal. For a month, I had asked my friends to scour the local pharmacies for painkillers, which cost five times what they used to. And it turns out all this was for nothing.

If there was no siege, of course it would be different – I could get out of east Aleppo, see another doctor, go to Turkey for treatment. As it is, I’ll try to get by on painkillers until the road is open again.

Most of my family are in Turkey, but I stayed in east Aleppo to be with my friends. My sister came back for a visit, but the day she arrived her house got bombed and now she’s trapped inside east Aleppo too.

Now I can’t even leave my room. I miss my neighbourhood, I miss the streets outside. I have to look at photographs to remind me of how they look. But my friends visit me every day.

During the bombing raids, I stay in my room – it’s not worth the effort to go downstairs. This house only has three floors, and the missiles they are using tear right through buildings to the ground. I can't sleep. All the doors here are broken now and the building next to mine was destroyed. The roads are closed. I don't know how, but I'll try to leave the house.

*Names have been changed; patient interviewed 24 and 28 November 2016