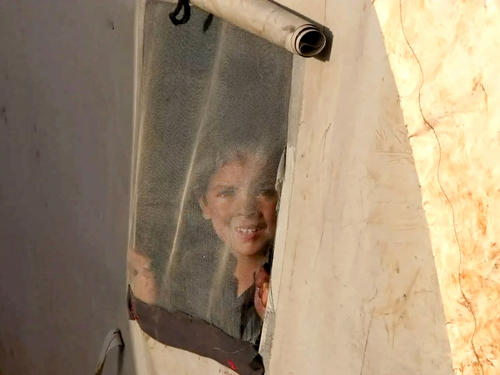

Over the last seven years, a new crop has been growing in the fields of Idlib, northern Syria. Among the rolling hills and olive groves, sagging tents have sprung from the ground to house hundreds of thousands of Syrians who have fled from fighting. “This is our fourth displacement,” says Suleiman, who originally comes from the countryside of eastern Hama. He explains how war forced him from place to place before he ended up four months ago in this white tent, stained red by the earth, with his wife and four children. “When we first arrived, some NGOs came to our aid, but now for three months there’s been nothing.”

More than half of Idlib’s population of roughly two million people are displaced. The arrival of 80,000 more people in the last two months from east Ghouta, rural Damascus and north Homs is further stretching the ability of local residents and humanitarian organisations to address their needs. While some families are crowded into rented accommodation, many others are living in camps, some of which lack basic services. “We are 135 families camp here in the camp,” says Abu Ahmad, who is living in a field near Atmeh. “There are just six or seven toilets for all of us. You have to wait for half an hour to use them, and they are not clean.”

As doctors, we have a duty to remain here and help all these people afflicted by displacement.Dr Mohammed Yacoub, an MSF team leader in one of the mobile clinics

In the face of these great needs, MSF has been ramping up its efforts to bring healthcare to hard to reach and underserved patients. “We have added three emergency mobile clinics to the two that were already operating in these camps,” says Hassan Boucenine, MSF’s head of mission for northwest Syria. “These people are living in very overcrowded camps crammed into a small area, and they have already lived through years of war. We are doing our best to provide care in places where it is not at all easy to see a doctor or afford private care.”

As well as the mobile clinics, MSF runs two hospitals in this part of the northwest, supports 14 other hospitals and health centres, runs two clinics for non-communicable diseases and provides vaccinations by running or supporting four dedicated vaccination teams, with vaccinations also incorporated into other activities.

“As doctors, we have a duty to remain here and help all these people afflicted by displacement,” says Dr Mohammed Yacoub, an MSF team leader in one of the mobile clinics. “At first our work was mainly treating routine diseases – bronchitis, throat infections, diarrhoea – but recently many displaced arrived from different parts of the country and many infectious diseases have spread among them because of overcrowding.”

An unsafe destination

Over the last year, many of the remaining enclaves of opposition-held territory in Syria have been partially evacuated after deals ended fighting with the Syrian government. While each ‘reconciliation’ agreement has been different, they have all resulted in many civilians leaving their homes and moving to new areas at the same time as fighters who had negotiated safe passage in convoys.

These people, as well as those who fled from areas in the south of Idlib governorate, have made up the most recent waves of arrivals to Idlib, an area where people have sought sanctuary for years.

“Some planes came and bombed our village, and I lost my arm, as you can see,” says Safwan as he gestures to the stump where his right arm used to be. “The regime bombed our village again so we moved here, to the mountains. An NGO gave us tents and we’ve lived in them for three, nearly four years now.”

Idlib is not by any means a safe haven. Active conflict continues between the government-led coalition and non-state armed groups around the fringes of the area, and Syrian-led coalition shelling and bombing persists, even deep into the areas outside the government’s control. Fractious relations between the armed groups in Idlib may also be behind waves of assassinations in the last months.

People’s displacement has not marked the end of their suffering, with difficult living conditions adding to concerns about security.

Escaping under fire

Yasir fled from Hama with his wife, 12 children, daughter-in-law, and grandson. “The day we left,” he remembers, “we left at night and we were bombed. I had put all the provisions for my children and clothes in the car – but now it’s all gone, stolen. We are without everything. We had to take our children and run.”

He, and many others like him, arrived in the camps with basically nothing. “I just have this shirt that I’m wearing,” Yasir says. They are living now in tents that are exposed to the cruel cold of winter and the ferocious heat of summer. A lack of sanitation means that open sewers run down the street in some camps, and residents complain of the large numbers of insects that swarm their tents.

“We fled under heavy bombing, walking from night until morning,” says Fawzia. “No food, no drink, no nothing.” The situation in the camps has not been any better, she says. “We have nothing but this tent. One night I couldn't breathe inside the tent, and I spent two hours outside, trying to breathe. It just like suffocating – we are 14 in the same tent.”

Mothers describe a constant struggle to find enough food to feed their children. Four per cent of under-fives seen in MSF mobile clinics in the first months of 2018 were moderately malnourished – a small but persistent number. “I went to a private clinic to ask for milk but they wouldn’t give me any. We aren’t able to buy anything,” Fawzia said.

As the wind blows dust through the open tent flaps, Fawzia demonstrates how she is forced to wash five of her youngest children in a small amount of water without cleaning products, and says that she lacks nappies for them.

Treating Idlib’s displaced

At one of MSF’s mobile clinics, three trucks pull together to create a space shaded with a piece of tarpaulin, and the team gets to work. A data officer records the details of the people who have come for treatment, before a nurse takes measurements from patients. A doctor sees patients in his room in one of the trucks, a midwife provides ante- and postnatal consultations in her room, vaccinations are performed and a pharmacist dispenses prescribed medication.

“People’s exposure to the elements means that respiratory diseases are the most numerous sicknesses we treat in the mobile clinic in this season,” says Dr Sonja van Osch, MSF medical coordinator. “We are also seeing skin diseases in large numbers because of the living conditions, and cases of diarrhoea because of a lack of sanitation.”

Non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, also make up a large part of the clinic’s work: these illnesses require follow-up and sustained treatment, which can be hard to access for displaced people.

Such services, provided free of charge, are even more important at a time when all people living in the area – new arrivals and residents alike – face problems accessing health services due to a lack of doctors, high prices, and a lack of high-quality care.

There are many organisations working to assist people in Idlib, but their needs are not being adequately met. Where there are clear gaps, MSF is stepping in to assist with its mobile clinics, despite the insecure environment. “Sometimes there are security issues that our cars are exposed to, and sometimes there are explosions,” says Dr Yacoub. Despite all the difficulties, he takes pride in his work and recognises the importance of the services provided by the mobile clinic. “We are giving something to those who are unfortunate and isolated,” he says.

Across northwest Syria, MSF runs two hospitals directly and supports 14 hospitals and health centres. The organisation also operates five mobile clinic teams, two non-communicable disease clinics and four vaccination teams. MSF also provides distance support to around 25 health facilities countrywide, in areas where teams cannot be permanently present.

MSF’s activities in Syria do not include government-controlled areas since MSF’s requests for permission to date have not resulted in any access being granted. To ensure independence from political pressures, MSF receives no government funding for its work in Syria.