Our COVID-19 response focuses on three main priorities:

• supporting authorities to provide care for COVID-19 patients;

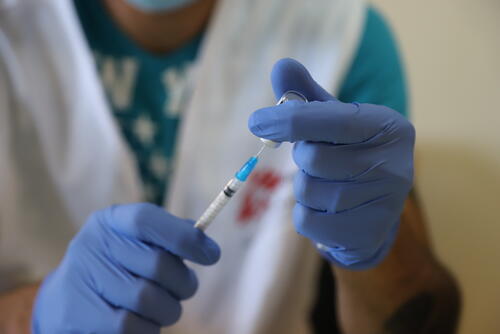

• protecting people who are vulnerable and at risk, including via vaccination;

• and keeping essential medical services running.

Across our projects, MSF teams have implemented infection prevention and control measures to protect patients and staff. Having access to protective equipment, to COVID-19 tests, to oxygen and to drugs for supportive care or treatment, is essential as COVID-19 spreads in countries with little access to these tools.

Teams are also vaccinating people to protect against COVID-19 in multiple countries. We’re also speaking out on the need for equitable access to COVID-19 tools, including vaccines and treatments.

Scroll down to read the latest news and articles from our COVID projects.

Key concerns during COVID-19

We’re concerned how people living in precarious environments will be affected by the pandemic. People living in overcrowded conditions, on the streets, in makeshift camps or substandard housing are at particular risk of COVID-19. Many are already in poor health and excluded from the formal healthcare system. We know social or physical distancing will be infinitely more difficult or impossible for these groups of people. We have to find other ways to help people keep themselves protected such as mass distributions of soap, water, and, in carefully considered circumstances, reusable cloth masks.

During the pandemic, babies will still be born, people will still need treatment for diseases like HIV and TB. Maintaining access to healthcare for non-COVID-19 needs is essential, including in MSF regular projects. In our projects all over the world, our teams are ensuring infection prevention and control measures are in place, setting up screening at triage zones, creating isolation areas, and providing health education to local staff and people

Protecting healthcare workers from contracting the virus is paramount for ensuring the continuity of care for general and COVID-related health needs. However, the global shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) pose a great threat. Healthcare workers must have access to the equipment they need to do their jobs safely and effectively; countries should show solidarity and share protective equipment wherever possible.

We also must protect those most at risk of severe forms of the illness. With COVID-19, that largely means the elderly, so much of our COVID-19 response focuses on strengthening the infection control measures and protection of the elderly in nursing homes. It also concerns those who have another illness, such as diabetes, HIV or tuberculosis. We don’t yet know what the impact will be for children who suffer from severe malnutrition, or for communities that have been hit hard by measles epidemics, such as in DRC or Chad.

There should be no profiteering on emerging drugs, tests, vaccines and other tools used for this pandemic. Governments must take any necessary measures – including overriding patents and other monopolies, and introducing price controls – to ensure production, supply, and availability of essential tools at an affordable price for all. High prices and monopolies of tools will only result in rationing, which will then prolong the pandemic. In addition, prices of other essential supplies such as masks, and other PPE must be kept accessible. Once approved or available, tools must be prioritised for healthcare and frontline workers first, and then supplied based on equity and need.

Featured

Responding to COVID-19: Global Accountability Report 4 - January to April 2021

Responding to COVID-19: Global Accountability Report 3 - September to December 2020

Responding to COVID-19: Global Accountability Report 2 – June to August 2020

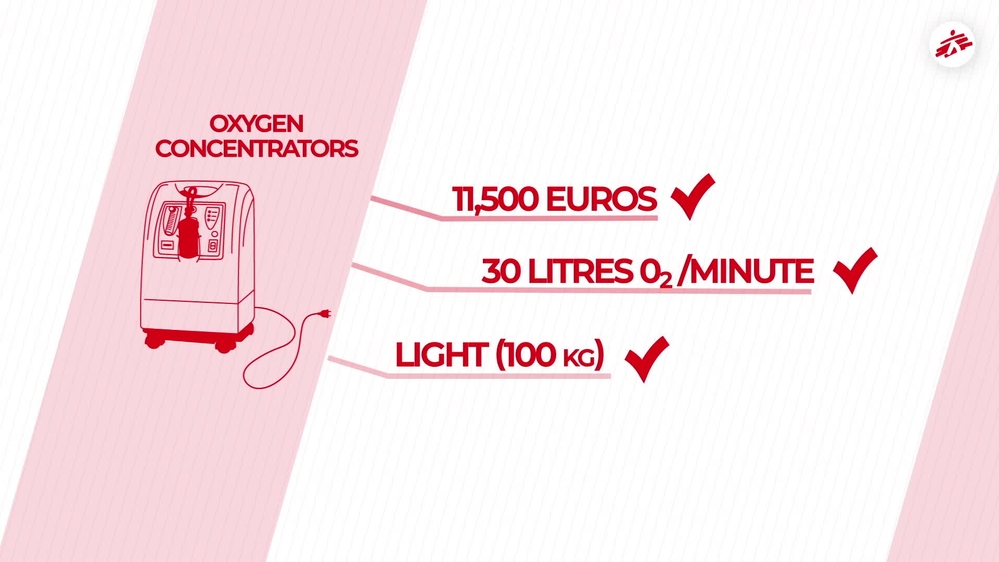

Supplying oxygen to COVID-19 patients: Essential, and a huge challenge

How do we supply oxygen to COVID-19 patients?

We cannot treat a person seriously ill with COVID-19 without oxygen. 80 per cent of people hospitalised because of COVID-19 need between three and 15 litres of oxygen per minute. For the 20 per cent who remain, the needs are more severe: more than 20 litres per minute.

Oxygen is therefore vital for them: without it they risk dying. But how do we give oxygen to our patients? What are the constraints of these various methods? And how do we put these systems in place in the countries where we work, particularly in a conflict context like Yemen?

Lack of a real IP waiver on COVID-19 tools is a disappointing failure for people

“Broken” humanitarian COVID-19 vaccine system delays vaccinations

Vaccinating people with comorbidities in South Africa

The restless challenge of tackling COVID-19 in Iraq

Responding to COVID-19 during political crisis in Myanmar

Responding to COVID-19: Global Accountability Report 5 - May to September 2021

In an unequal world, our response to COVID-19 cannot be one size-fits-all

Pandemic preparedness and response: some lessons learnt

Providing support for COVID-19 in Manipur

Worst wave yet of COVID-19 in northern Syria overwhelms health system

European Union: more empty promises about global COVID-19 vaccine equity