It’s a sunny morning in Nur Shams refugee camp, in Tulkarem, West Bank, Palestine. Over 20 women are filing into a room set up by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) staff, sitting in a circle and chatting over Arabic coffee. In the middle of the room, there is a table with gauze, tourniquet devices and charts explaining blood flow in the human body. This is MSF’s ‘stop the bleeding’ training.

Most women gathered in this room have little to no medical training, but trauma wounds and severe bleeding are not new to them. They are here to learn how to care for wounds, apply tourniquets, and provide basic first aid to family members and neighbours until they can reach medical care during frequent military incursions by Israeli forces.

“We experience raids, bombings, and injuries from shootings,” says Saeda Ahmad, a participant in the training. “We often have an injured person right in front of us. In such situations, it’s important for us to have the knowledge and background to properly administer first aid.”

“During raids, it's extremely difficult for ambulances to reach the scene,” continues Ahmad. “That’s why everyone in the camp needs to have some knowledge of first aid. So that we ourselves can help the injured person.”

'Stop the bleeding' training in Tulkarem, West Bank

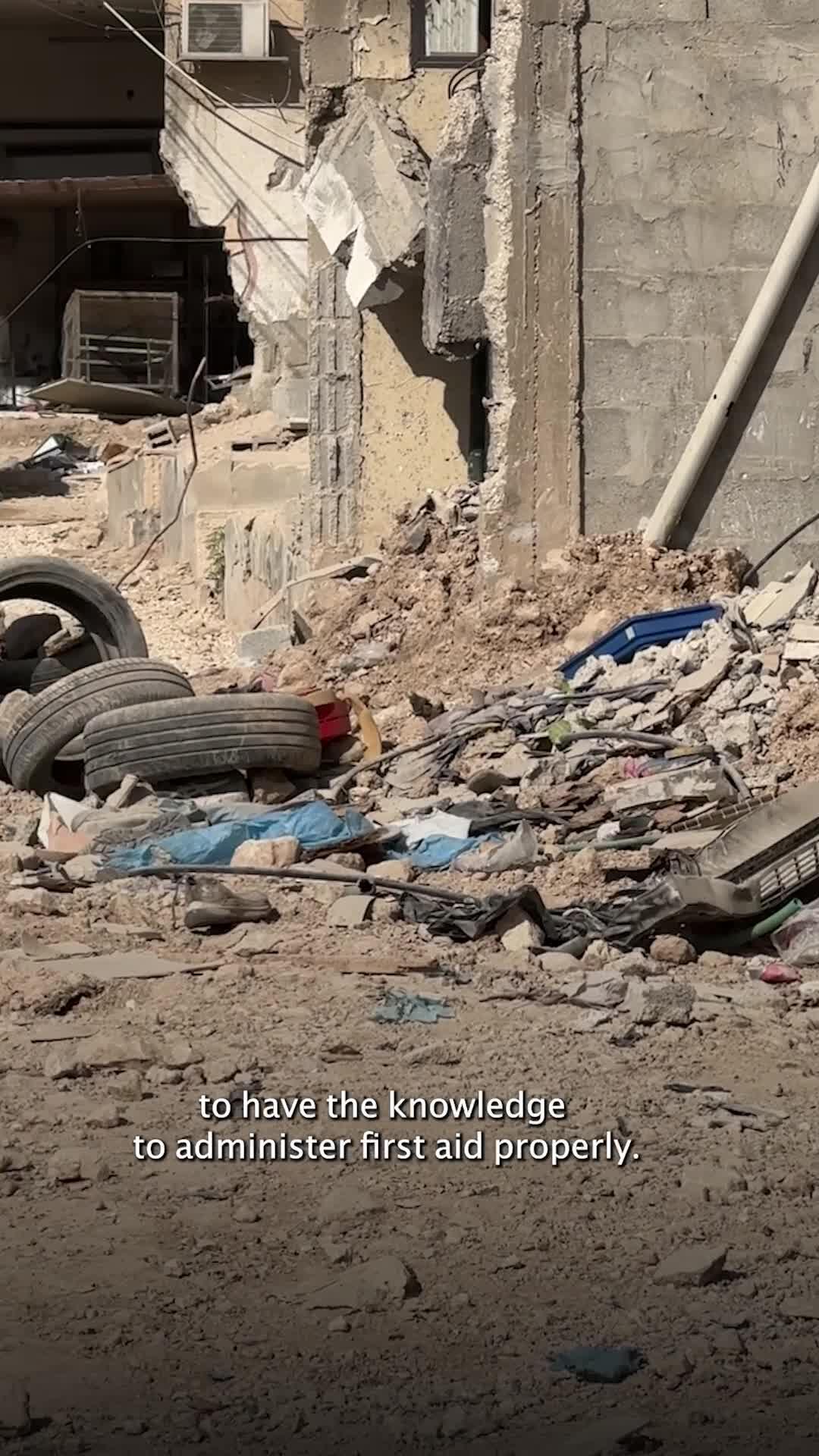

Here, military raids by Israeli forces are becoming increasingly frequent, and blockages of access to healthcare are part of the modus operandi. Roads are blocked, ambulances cannot move, healthcare workers are harassed and targeted or otherwise hindered, and wounded people often cannot reach hospitals.

Incursions from Israeli forces are also increasing in violence and intensity; on 3 October, 18 people were killed in an airstrike on Tulkarem refugee camp. The use of drone strikes, air strikes and other bombardments by Israeli forces, in often densely-populated areas and refugee camps, has become increasingly common. Incursions are also increasing in length, and not only here; last August, in Jenin, north of Tulkarem, Israeli forces launched a large-scale military incursion that lasted nine days.

In this context of constant violence and insecurity, people in the camps have spoken with MSF mental health staff of the deep psychological impacts of these raids. Military incursions by Israeli forces reshape the lives of people, stripping them of normalcy and any sense of safety.

People are always in the aftermath from the last incursion, rebuilding torn up streets and destroyed houses, while holding their breath until the next military raid. Our teams are also providing psychological first aid to residents in the camp, to address the significant mental health issues stemming from the impact of these incursions, which affect all residents, but particularly children.

During raids, it's extremely difficult for ambulances to reach the scene. That’s why everyone in the camp needs to have some knowledge of first aid.Saeda Ahmad, training participant

“The situation is very difficult. The children in the camps are afraid to go to school, as they fear a raid might happen while they are there,” says an MSF community health educator for MSF in Tulkarem. “In their home life, stability has vanished. People remain on edge.”

“Children have stopped playing in the alleys. They spend most of the time at home and are not able to go out,” says our health educator. “They can’t even go out to buy what they need because their parents won’t let them, out of fear that a raid or incident might occur while they’re outside. There are children whose entire playtime has become centred around the violence they have experienced.”

In a context of fear and insecurity, it becomes impossible for people to live a normal life or plan for the future. Training like ‘stop the bleeding’ can provide some sense of control over the situation, by giving residents the tools to act in a medical emergency during an incursion. But their very existence highlights the direness of the situation in the West Bank.

In this room, as participants practice wrapping gauze around each other’s arms, emotional wounds also reveal themselves. Participants share stories of the violence they have experienced, in conversations, stories, and photos of killed family members on a phone’s lock screen.

The psychological wounds, also, are deep. And mending them takes more time than applying pressure or tightening a tourniquet.