When Zakya Seid arrived in late-pregnancy at a hospital supported by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Am Timan, Chad, she could no longer feel the baby moving inside her womb. Unfortunately, her fears were realised: the medical team could not save the baby as he was already dead. During her pregnancy, Zakya had contracted hepatitis E, a viral disease transmitted mainly by polluted water. For many people, the disease has no symptoms and is not life-threatening, but for pregnant women in particular it can be extremely dangerous. Zakya survived, but her baby's life could have been spared if she had had access to safe drinking water.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), two billion people regularly drink water that is contaminated by faeces, putting them at risk of contracting a host of waterborne diseases.

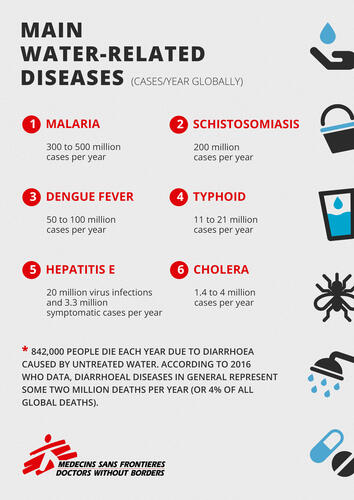

Some 842,000 people die each year from diarrhoeal diseases caused by contaminated water, according to WHO, most of them children under the age of five. Each year, 361,000 of these infant deaths could be prevented by installing proper water and sanitation systems.

Aline Kaendo was able to save her son. As soon as five-year-old Aristide got sick, she took him to the cholera treatment centre set up by MSF in Minova, in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The boy was one of 55,000 people who contracted the disease in 2017, in the country’s worst cholera outbreak for 20 years. In 2018, there were more than 25,000 cases of cholera, and by November of that year, 857 people had died from the disease. The outbreak, which took place during a prolonged drought, affected 24 of the country’s 26 provinces, and is still not completely under control. Water shortages forced people to seek alternative sources of water, which often turned out to be unsafe.

The epidemic even reached the capital, Kinshasa. Marie was a patient at MSF’s cholera treatment centre in the Camp Luka neighbourhood. “I was very weak and then we tried to take a moto-taxi, but everyone refused us,” she said. “My husband had to carry me on his back for three kilometres to get me here. There’s a lot of stigma attached to cholera here in Kinshasa. It's a shameful illness.”

What does an epidemiologist do in MSF? (ENG)

The struggle to get hold of clean water has a particular impact on women's lives. Women are often tasked with fetching water from distant water sources – long journeys on which they are especially vulnerable. In the four-month period between October 2004 and February 2005, our team in Sudan’s Darfur region provided care for 500 women and girls who had suffered sexual violence. Most reported being attacked when they left their villages to collect firewood and water.

More recently, 10 women who had survived sexual violence arrived at our hospital in Bossangoa, Central African Republic, in March 2018. The women reported that they were in a larger group fetching water and washing clothes when they were approached and abducted by gunmen. More than 15 days went by after the attack before they dared to seek medical care, while others in the same group never sought help. Again, the lack of easy access to drinking water put their safety and lives at risk.

Access to water and dignity (ENG)

MSF’s response

We provide lifesaving medical care to people affected by humanitarian crises. Although building water and sanitation infrastructure is not MSF’s core work, it is often a key element in preventing or containing the spread of diseases. It is also essential in making sure that people living in crisis-hit regions can access clean water and latrines without risking their safety.

Water and sanitation specialists – or watsans – carry out various activities to ensure that the people we assist have clean water and a safe environment in which to live. Watsans are in charge of the water supply; they are supported by health promoters who engage with the community to raise awareness of good hygiene practices.

What does a WATSAN expert do in MSF? (ENG)

The watsan team plays a key role in responding to crises. In 2018, water and sanitation specialists were sent more than 200 times to different MSF projects. In 2017, we spent €11,441,080 on water and sanitation equipment and material. The scale of this investment becomes clearer in the light of a WHO study from 2012: every US$1 spent on sanitation saves US$5.50 in health costs.

Water-related diseases

Cholera is a disease that, without treatment, kills 50 percent of people infected. However, with proper medical care, the mortality rate drops to just two percent. When there is an outbreak, cholera vaccinations are an effective way of containing the spread of the disease. It is also easily preventable with good hygiene practices and a functioning sanitation system.

In 2017, MSF treated 143,100 cholera patients in 13 countries – up from 20,600 cases the previous year. This increase was largely due to the cholera epidemic in Yemen, biggest ever seen in Yemen, and one of the biggest in recent world history. We treated more than 100,000 people in 37 cholera treatment centres and oral rehydration points across the country. The epidemic showed some of the devastating side effects of war. With Yemen’s water, sanitation and health infrastructure destroyed by the current conflict, the country has been hit by a number of diseases, including cholera, that had been under control.

Soon after, Yemen was hit by another epidemic related to the destruction of its water and sanitation infrastructure. This time it was malaria. We treated more than 10,000 people for the disease in Yemen in 2017. The absence of sewage treatment facilities was a significant factor in the outbreak, as the mosquitoes that transmit malaria breed in dirty, standing water.

The problem is not limited to Yemen. Malaria is one of the most commonly occurring diseases among MSF patients worldwide. In 2017 alone, we treated 2,520,600 people for malaria. Other diseases transmitted by mosquitoes which breed in standing water – such as dengue fever, chikungunya, yellow fever and the Zika virus – can also be prevented with efficient water piping systems.

In crowded environments, the harmful effects of a lack of clean water become magnified. In emergency situations, WHO recommends a minimum of 15 litres of water per person per day for drinking, cooking and washing – but supplying even this amount can be challenging. In February 2019, after violence erupted in the city of Rann, in northeastern Nigeria, more than 35,000 people fled to Cameroon, where they slept out in the open in a makeshift camp. An MSF team joined with other emergency organisations to distribute 240,000 litres of water per day to the refugees, but even this represented the equivalent of just seven litres per person per day – less than half of the WHO minimum standard for emergencies.

In camps for refugees and internally displaced people, a lack of clean water and latrines create an environment where diseases can easily spread. If it rains, flooding may contaminate existing water points. This happened in 2017 after hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees fleeing violence in Myanmar arrived in Bangladesh’s Cox's Bazar district. With so many people living in close quarters in improvised camps, there were outbreaks of a number of infectious diseases. On top of this, the arrival of the monsoon season caused flooding and mudslides due to the lack of water flow systems.

Perspectives

Climate change is likely to exacerbate existing crises. By 2025, WHO estimates that half the global population will live in water-stressed areas.

The relation between drought and diarrhoeal diseases, and between drought and malnutrition, are already well known. If droughts become more prolonged due to global warming, the effects on people’s health will multiply. In April 2017, an outbreak of acute watery diarrhoea affected the Doolo area of Ethiopia amidst one of the worst droughts in three decades. Every year, between May and September, our teams in Africa’s Sahel region expect to see the health of hundreds of thousands of people suffer as their food stocks run low in the dry season.

Global warming may also exacerbate other crises, including natural disasters, mass displacement and conflict.

"There is an interrelationship between low water quality, water scarcity, conflict and the displacement of people,” says Carol Devine, MSF humanitarian affairs advisor. “We are also seeing more extreme weather events, for example in the Philippines, where after flooding there is a greater risk of waterborne diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera and bacterial infections, as well as a greater risk of dengue fever. We are seeing associated cholera and dengue epidemics in places like Bangladesh and Yemen, which we did not see so often in the past."

Water is a vital resource on which the health and dignity of human beings depend. With such a challenging future, it is more important than ever that water and sanitation infrastructure meets the needs of people caught up in crises.