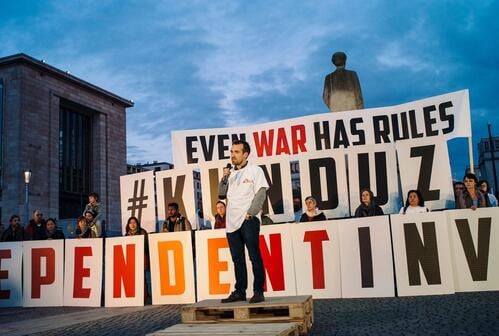

In October, the MSF Kunduz trauma centre in Afghanistan was targeted by US airstrikes, which resulted in the deaths of 14 staff, 24 patients and four patient caretakers. Over one million people in northeastern Afghanistan remain deprived of high-quality surgical care as a result.

Our thoughts go out to the friends and families of those who died. We also remember our colleagues who tragically lost their lives this year in a helicopter crash in Nepal and our colleague who was killed in the Central African Republic (CAR).

We take this opportunity as well to tell Philippe, Richard and Romy, our staff who are still missing in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), that they are not forgotten.

Attacks on healthcare and the subsequent suffering of civilians

The repercussions of attacks on health facilities continue long after the initial impact. The destruction results in thousands of civilians being deprived of essential medical care at a time when they need it most.

MSF was able to work in Kunduz thanks to negotiated agreements with all parties to the conflict that they would respect the neutrality of the medical facility.

An independent and impartial inquiry into the facts and circumstances of the attack is needed, as we cannot rely only on the US’s own internal military investigations.

Aerial bombardments of hospitals are not new, but neither can they be dismissed as simple ‘mistakes’. The bombing in Kunduz attracted extensive media coverage because an international organisation was targeted by the US military.

At a time when attacks on healthcare are intensifying and civilians are paying the price, what is often an overlooked issue was pushed into the international spotlight.

In January, an MSF hospital in South Kordofan, Sudan, was bombed by the Sudanese Air Force, injuring one patient and one staff member. This same hospital had also been bombed in June 2014.

Medical facilities were also shelled in Ukraine at the beginning of the year, but it is in Syria where we really see medical care becoming the target of both deliberate and indiscriminate violence.

Laws passed in 2012 effectively criminalised providing medical aid to the opposition in Syria. Government forces have since strategically attacked medical facilities and medical personnel, including doctors, nurses and ambulance drivers, with the aim of harming the opposition; an alarming trend of impunity.

In 2015, there were 94 aerial and shelling attacks on 63 MSF supported facilities, causing varying degrees of damage and, in 12 cases, resulting in the total destruction of the facility; 81 MSF supported medical staff were killed or wounded.

Towards the end of the year, medical facilities in Yemen were also bombed. Airstrikes in October carried out by the Saudi-led coalition destroyed an MSF-supported hospital, leaving over 200,000 people without access to medical care.

As a result of these repeated attacks on medical facilities, some civilians regard visits to hospitals as riskier than not seeking medical care at all. The ‘security at all costs’ logic means that humanitarian aid is welcomed when it serves national security interests but is restricted, even attacked, when it does not.

People on the move

Fleeing violence

Conflict and violence have forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes and their countries this year. In early 2015, large numbers of refugees crossed into Tanzania to escape election-related violence in Burundi.

By July, as many as 3,000 people were arriving in the country each week, and it was estimated that 78,000 Burundians were sheltering in Nyarugusu camp.

Since the beginning of the Syrian crisis in 2011, it is estimated that more than 1.5 million Syrian refugees and Palestinian refugees from Syria have arrived in Lebanon and the small country is struggling to cope. In Jordan, over 600,000 Syrian refugees have been registered to date.

In the Lake Chad region in western Africa, 2.5 million people in Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria fled their homes following attacks by Boko Haram and sought shelter and protection in refugee or internally displaced person camps. Counter-offensives by armed forces have only added to their suffering.

MSF works in all the countries mentioned above, for example conducting vaccination campaigns in Tanzania, providing free treatment for chronic diseases in Lebanon, running a reconstructive surgery project in Jordan and, despite insecurity, deploying medical teams to the four affected countries in the Lake Chad region.

A large part of the global responsibility for hosting refugees is shouldered by countries immediately bordering conflict zones, a fact that rarely makes the headlines.

The journey to Europe

During 2015, at least 3,771 people died while attempting the sea crossing to Europe. MSF conducted search and rescue operations at sea and provided assistance at Europe’s entry points and along the ‘migration route’, in a telling indictment of Europe’s policies towards the displaced.

Due to a lack of safe alternatives, people resort to smugglers and risk their lives on dangerous and uncertain journeys to escape war and persecution, or because they are in search of a better and safer life for themselves and their families.

The humanitarian crisis that has unfolded on the borders of the European Union (EU) is largely policy-driven, a result of the EU’s failure to put in place effective and humane policies and responses to deal with the unprecedented, but in many ways foreseeable, movement of people.

The lack of political will, which became so obvious when dealing with Ebola, was again evident with the ‘migration crisis’. World leaders turned their backs, hoping that the situation would remain confined to countries far away, despite the fact that in some cases they themselves are contributing to the suffering.

Four of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council – Russia, the US, France and Britain – are involved in bombing Syrian civilians.

There has been an unacceptable lack of recognition of the reasons why people are fleeing their countries, and most efforts to date have concentrated on deterrence measures aimed at stemming the flow of refugees and migrants arriving on EU soil.

It is estimated that one million people fled to Europe in 2015, and that almost 50 per cent of them came from Syria. With no end to the war in sight, the numbers will only continue to grow.

The EU has externalised the management of its borders to Turkey, handing over billions of euros in return for a clampdown on Syrians attempting to make the crossing.

The end result of border closures from Europe all the way back to Syria is that civilians are being trapped in one of the most brutal wars of our times.

Ongoing and intensifying violence in South Sudan

Civilians in South Sudan continue to be exposed to extreme levels of violence. In 2015, rape, abduction and execution were commonplace in some parts of the country, and regional and international attempts to resolve the conflict failed.

MSF teams in Unity state witnessed villages being burnt to the ground and crops looted and destroyed. Hundreds of thousands of people fled into the bush and swamplands, where they had no access to assistance for months at a time.

MSF medical facilities were looted or attacked on three separate occasions and five South Sudanese former staff members were killed.

MSF struggled to access vulnerable populations in the worst-affected areas but was able to deliver lifesaving medical care at its projects on the frontlines and through mobile clinics.

Compounding the severe humanitarian crisis, South Sudan also experienced the worst outbreak of malaria that MSF has ever witnessed in the country and its second outbreak of cholera in two years.

Response and research and development (R&D) for epidemics

Towards the end of 2015, the Ebola outbreak was declared over in Sierra Leone and Guinea, but new cases have since been reported.

The public health systems in the affected countries in West Africa have been devastated and routine vaccination campaigns, including for measles, tetanus and polio, have fallen by the wayside.

Reinstating non-Ebola-related healthcare and re-establishing people’s trust in it is crucial to ending the epidemic. However, this is further complicated by a lack of trained medical personnel. It is estimated that over 880 medical staff contracted Ebola in the three worst-affected countries, and over 500 died.

There are also over 10,000 Ebola survivors, many of whom are still long-term patients, presenting with mental health issues, general weakness, headaches, memory loss, muscle pain and eye problems.

Ebola is not the only disease threatening populations, though. Outbreaks of measles, meningitis and cholera, for example, are common in places where people are forced to live in unsanitary conditions such as refugee camps, or where routine vaccinations have been interrupted.

The extremely high mortality rates during the recent measles epidemic in Katanga region in DRC illustrate how preventive strategies over the past decades have failed. MSF vaccinated over 300,000 children between June and September, and treated 20,000 patients for the disease.

In 2015, the MSF Access Campaign launched its ‘Fair Shot’ campaign in a bid to lower the prices of vaccines, in particular for pneumococcal disease. There

has been a 68-fold increase in the price for the package of childhood vaccines over the last decade.

Malaria also continues to be a major challenge around the world, despite elimination strategies, and there are outbreaks of less common diseases such as yellow fever, chikungunya and Lassa fever.

In 2015, there was a large outbreak of Zika virus (first identified in humans in 1952) in the Americas, which resulted in the World Health Organization declaring it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in early 2016. Very few diagnostic tests are currently available, and there is no specific vaccine or treatment.

R&D must be undertaken with communities and environments in mind to ensure that diagnostics, vaccines and treatments are effective, accessible and affordable, and adapted to the contexts where they are needed most.

Ebola exposed a global R&D infrastructure that is unfit for purpose; it cannot help save lives during an emergency.

We should be conducting safety studies and working out ethical frameworks during inter-epidemic phases in order to be prepared. This would allow fast-track use of experimental drugs and vaccines during an outbreak and efficiency trials as an epidemic peaks.

Yet, all too often, we scramble to act only as an epidemic peters out. We must act ahead of epidemics, not at the tail end.

Over the past few years MSF has had to adapt its response to meet the challenges of individual contexts, and in Syria in 2015 we continued to run health facilities in the country but also offered support, donated medicines and equipment, and set up partnerships with networks of local doctors.

Despite difficult conditions in CAR, MSF staff continued to address basic and emergency healthcare needs across 13 prefectures and 15 localities by carrying out vaccination campaigns, operating mobile clinics and providing emergency surgery, specialised care for victims of sexual violence and treatment for malnutrition.

Out of the spotlight, tens of thousands of MSF staff treat patients with HIV and tuberculosis, malaria and malnutrition, offer specialist care to mothers and children, and conduct vaccination campaigns and surgery in nearly 70 countries around the world.

We want to pay tribute to them, and to thank our supporters for making our work possible.