Executive Summary

ACT Now. This is an urgent call to international donors to join African countries in implementing World Health Organization (WHO) treatment guidelines for malaria. On the advice of international experts, WHO recommends African countries facing resistance to classical antimalarials to introduce drug combinations containing artemisinin derivatives – artemisinin-based combination therapy, or ACT for short.

Artemisinin derivatives have attributes that make them especially effective: they are highly potent, fast-acting (parasite clearance is fast and people recover quickly), very well tolerated and complementary to other classes of treatment.

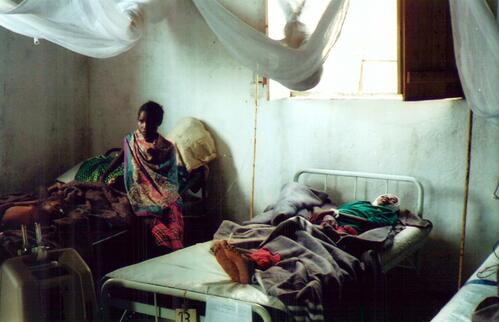

Implementation of new malaria recommendations is a matter of life and death in Africa, where malaria kills between 1 and 2 million people each year. Sickness and death from malaria account for 30-50% of hospital admissions and a yearly loss of US$12 billion on the African continent.

The WHO-led global malaria eradication programme launched in the 1950s sought to eliminate the disease via vector control and effective treatment. The eradication programme was successful in some parts of Asia, North America and Europe, but bypassed sub-Saharan Africa. In 1969, the focus switched to the less ambitious goal of control through treatment. At the time, the treatment of choice was chloroquine, dispensed in a three-day course. This effective treatment campaign led to falling death rates through to the early 1980s.

However, since the early eighties, the situation has stopped improving, and has in fact been getting dramatically worse. Average annual cases were four times higher between 1982 and 1997 compared to the period 1962-1981. Death rates have also jumped: hospital studies in various African countries have documented a two- to three-fold increase in malaria deaths. The continuing use of ineffective drugs despite spectacular levels of resistance is leading to increased treatment failure.

While African countries are heeding the advice of world experts to switch from old failing single-drug treatments to combination treatments, they are being forced to switch to stop-gap, less expensive combinations because of a lack of resources.

Why is MSF so focused on treatment?

Effective malaria control requires strong political will from endemic country governments that translates into implementation of comprehensive prevention and treatment programmes. But while the international community has been willing to do everything possible to augment prevention, there has so far been no concerted drive to support improved treatment.

In its projects MSF supports prevention as an integral part of effective malaria control. There is no controversy there. The debate that we think needs to be stimulated is on treatment.

After extensively documenting resistance to current treatments in MSF projects and carefully considering data gathered by ministries of health in endemic countries that MSF decided to switch to ACT in all its programmes. The decision was articulated in an October 2002 internal MSF malaria policy paper:

To ensure good patient care now and in the future, and to prevent the further spread of the disease in intensity and into new populations, MSF believes it is essential to use artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) in all our programmes where there are patients with falciparum malaria, and to explore all avenues open to MSF to assist governments to do the same in affected countries.

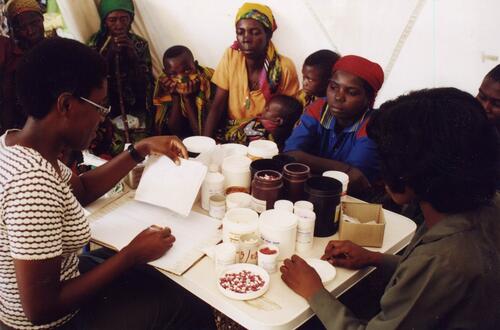

Since October 2002, implementation of this policy has focused simultaneously on switching to ACT in all MSF projects, and on advocating for and giving technical support towards increasing the availability of quality ACT drugs.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is seeking to change the current dynamic in which some international donor countries, such as the US and UK, are supporting a “leave it alone” approach while other countries have no publicly articulated policy. This report debunks detractors' arguments by demonstrating that ACT is safe and effective.

The lack of political and financial support on the part of donors means that endemic countries are often encouraged to “leave alone” failing malaria treatment and are not given financial and technical help to implement more effective strategies.

Without successful implementation of ACT therapies in the next decade, significant progress in controlling malaria will be impossible. This is because there are no miracle non-ACT combinations waiting in the wings, and because malaria control using prevention without effective treatment is doomed to failure.

How can we “leave alone” malaria treatment when one African child dies of malaria every thirty seconds?

This report defines The Malaria Problem, looks at What Works in malaria treatment and outlines what needs to be done to Make ACT a Reality.

Our recommendations convey what MSF thinks needs to be done to stem the tide of unnecessary malaria deaths in Africa. The idea is a simple one. Restock Africa with a malaria medicine that works.

- The World Health Organization must push for implementation of its own recommendation to switch to ACT

- Donors must stop wasting their money funding drugs that don't work and help fund efforts of endemic countries to make the switch to ACT

- Endemic countries need to back up their will to improve malaria control with increased budget allocations

- ACT must be provided to individuals free of charge, or at an affordable price

- International agencies and donors must provide technical support to facilitate both treatment implementation and upgrading international and domestic drug suppliers (with technology transfer and technical assistance to enhance production standards)

- UNICEF, WHO procurement and the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria must pool needs and make large orders to prime the drug production pump and bring down prices

- International and/or regional pre-qualification needs to be augmented to assist countries in identifying quality drug sources

- Concerned parties must undertake operational research to improve use of current tools

- Research & development for new drugs, new formulations and improved diagnostic tools must be placed high on the agenda and implemented through government supported research and non-profit initiatives such as the Medicines for Malaria Venture.