A year ago, a military offensive described by many as one of the largest urban battles of the century, came to an end.

After almost three years under the control of the Islamic State group, Mosul, a city of more than 1.5 million inhabitants, with a mix of ethnicities, sects and religions, was recaptured. The fight lasted nine months, because of its incredible complexity and numerous twists.

But what the battle also led to was a major crisis. One that persists to this day, in and around the city.

The beginnings

October 2016

A military offensive led by an alliance of the Iraqi security forces and an international coalition is launched to retake Mosul, Iraq’s second biggest city. This is a pivotal moment in the country’s battle against the Islamic State group, which has made Mosul its de facto capital in the country, since seizing it in June 2014.

Escaping the battle

October - December 2016

In the space of just two months, more than 100,000 people are already displaced by the fighting. MSF begins operating in camps receiving people fleeing Mosul and its surroundings. The organisation provides them with services such as psychological support and primary health care.

MSF also sets up clinics and hospitals to treat war wounded people, in the vicinity of the city. Some of these hospitals, such as the one located in Qayyarah, south of Mosul, are of major importance. This 30-bed medical and surgical facility provides emergency care to over 120,000 people in the space of a few months. The hospital’s doctors deal frequently with mass-casualty influxes.

Gunshots, blasts and so on… Today, I’ll operate on at least three, maybe four or five people.Aleksander Wroblewski, MSF surgeon

Halfway point

January - April 2017

By January 2017, the eastern part of Mosul is completely retaken, marking the battle’s halfway point. MSF starts to intervene in Muharibeen hospital: this is the first time the organization is able to work inside the city since the launch of the offensive. Other hospitals are set up in towns such as Hamdaniyah, where hundreds of patients come in for post-operative care, rehabilitation and psychosocial support.

I was going to a food distribution when something exploded in the street next to me. I was hit in the chest and arm by shrapnel. I passed through many hospitals before I came to Hamdanyiah. I have been here for a week now.Abdulrahman, an 11 year old patient, at the MSF post-op hospital in Hamdaniyah

In February, MSF deploys for the first time a mobile unit surgical trailer (called MUST) to operate as a fully functioning trauma facility in Hammam Al Alil. Made up of five trailers – containing an operating theatre, a recovery room and intensive care unit, a sterilization room, a pharmacy for medical supplies and a storeroom for logistical equipment – the unit enables the MSF teams located close to the frontline and in the middle of an emergency to conduct 100 surgeries without the need to bring in more supplies. This mobile unit surgical trailer becomes, for a while, the closest surgical facility to the ongoing fight in west Mosul. And more than half of all the trauma patients evacuated from the battle for West Mosul will end up passing through this hospital.

We wanted to design a surgical facility that could be transported on trucks and that would give us the flexibility to move quickly to reach people in need.Arnaud Badinier, MUST Project Manager

Hunger and trauma

May 2017

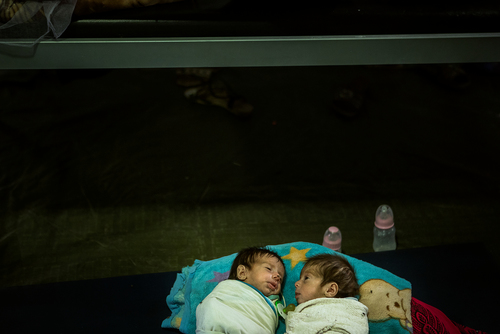

MSF starts receiving children suffering from severe acute malnutrition in some of its hospitals. This is unusual for a country like Iraq and is a testament to the hardships witnessed under the Islamic State group. This is only exacerbated when frontlines passed through residential neighborhoods, leaving Mosul’s inhabitants unable to leave their homes to buy food and other vital supplies.

Worst case scenario

June 2017

By the beginning of the summer 2017, over a million people have been displaced from Mosul and its surroundings since the launch of the offensive. The worst-case scenario that many humanitarian and UN agencies feared at the beginning of the battle has become a reality.

MSF adapts to the fast-evolving situation by entering in Nablus, an area strategically positioned to reach the war-wounded escaping from the final conflict areas of the Old City.

The hospital also opens maternity and pediatric care services that are still offered today: over the course of 2017, our teams managed close to 10 000 emergency cases, performed hundreds of surgical interventions, assisted more than 1400 deliveries and admitted close to 500 children to the facility.

Retaken

July 2017

On July 10, Prime Minister Abadi declares Mosul officially retaken, standing alongside top Iraqi military officials inside the Old City. This is the end of an offensive that stretched over 250 days, and has become one of the deadliest urban combats since World War II.

During the conflict, thousands of people were injured or killed, and over a million displaced. The frontlines cut through densely populated areas, which meant many people were effectively under siege, sometimes for months on end.

Only the walking wounded were able to access medical care, and even so, they often had to wait days before they could safely leave their homes and try to reach a clinic or hospital.Anja Wolz, Emergency Pool Manager

By the time the violence subsides, the infrastructure in West Mosul, including medical facilities, is decimated.

What now?

July 2018

A year has passed since the battle for Mosul officially ended, yet its consequences can be still witnessed inside and around the city.

For those who survived such a brutal battle, the scars of war remain, whether they are visible or not. The need for physical rehabilitation and mental health support far exceeds the availability of services in Iraq. And while most of Mosul’s population has now come home, tens of thousands Moslawis remain internally displaced in different parts of the country.

In parallel, reconstruction in Mosul and in many other recaptured areas in Iraq is moving excruciatingly slowly. Dozens of dead bodies remain under the rubble, especially in the Old City. This could lead to a public health hazard, as many people live in these partially destroyed homes and between collapsed walls. Additionally, landmines and other explosive remnants of war pose significant threats the inhabitants of the city.

One year on, and the MSF hospital in Nablus is still one of the only two functioning facilities in west Mosul. We also recently opened a post-operative care facility in the East, to assist the numerous war victims who still need further surgery. Additionally, MSF supports different Primary Health Care centres and organises punctual distributions for the people most affected by the conflict.

The battle might be over, but our work here is not, even a year later.