The camp itself is a health risk

Health conditions in the camp are alarming and deadly outbreaks of communicable diseases such as measles and diphtheria have already occurred. The upcoming rainy season, which usually starts in April, presents a greater risk of waterborne diseases such as acute watery diarrhoea, typhoid, hepatitis, malaria and dengue. Due to complete deforestation and the topography of the camps, the risk of mudslides and flooding during the upcoming rainy season is very high. The majority of the hastily-constructed latrines and wells require decommissioning or rehabilitation as flooding could contaminate drinking water. Heavy monsoon rains and high winds will potentially flood large areas and destroy flimsy shelters, which could lead to the further displacement of tens of thousands of people. Presently there appears to be nowhere for the Rohingya population to seek shelter.

Feeling unsafe at night

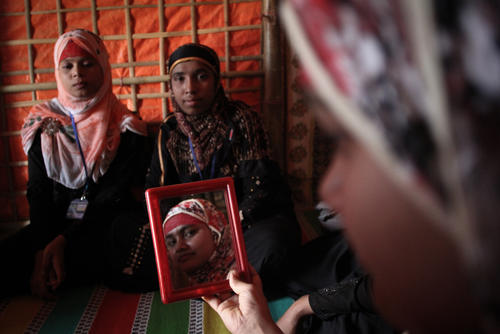

Both women and men in the settlement report feeling unsafe at night because of precarious shelter conditions, overcrowding, and the near-total absence of lighting after dark. Female-headed households, unmarried women, and unaccompanied children are particularly vulnerable, and MSF teams have heard reports of human trafficking. “Especially at night I’m very afraid. I do not walk outside alone, either going to the toilet or taking a shower. We are not able to lock our door and even my father cannot sleep. I feel as though something could happen to me at any time,” says 18-year-old Shamemar.

In 2017, the majority of women and girls who sought post-rape medical and psychological care in the MSF facility were abused in Myanmar. More recently, MSF teams have seen an increase in women seeking treatment for injuries sustained from intimate partner violence. Some of the women MSF treats have extensive physical injuries that require medical care and admission to our inpatient department. Some of the injuries we are seeing include contusions, lacerations, burns, fractures and strangulations. These women are also offered mental health counselling services. To ensure a humane and longer-lasting solution, the there is an urgent need to refer them to safe shelters.

Pregnancies resulting from rape

The barriers for women and girls to seek care after sexual violence are immense; they include stigma, shame, fear of reprisals and a lack of information about the care available. “Most of the women I speak with in the community don’t understand that violence requires medical attention,” says 35-year-old Zulia, one of the MSF community outreach team. To date, 230 survivors of sexual violence have been treated at MSF’s clinic, but because many never seek medical care, the number of survivors is likely to be much higher. Many arrive too late for post-exposure prophylaxis and emergency contraception. Women that have tried to end their pregnancies themselves often arrive at the clinic haemorrhaging or in septic condition. Others arrive with complications from having given birth unassisted and in unsanitary conditions. Women who became pregnant as a result of rape are sometimes unable to return to their community either before or after the birth. MSF is trying to find alternatives for these girls and women, although existing capacity in the camp is extremely limited. Safe alternatives are not widely available in Bangladesh, and even less so for Rohingya women.

Day-to-day stresses

Many refugees are traumatised by what they have experienced. This is compounded by the day-to-day stresses of camp life, including a lack of sufficient food, a lack of opportunities to make a living, and fear for their personal security. Refugees are arriving at MSF clinics with flashbacks of violent, traumatic events, anxiety, agitation, acute stress, recurring nightmares or inability to sleep and, in more severe cases, being unable to look after themselves or their families. Counsellors help people, individually and in groups, to talk about their experiences, process their feelings and learn to cope so that general stress levels are reduced. Rohingya refugees face uncertainty about their safety and future, not knowing if or when their conditions will improve, or if or when they will be able to return home.

By land, river and sea

Rohingya refugees continue to cross the border from Rakhine state, Myanmar. According to UNHCR, a total of 3,236 new arrivals entered Bangladesh in February alone, bringing the number to over 5,000 newly arrived refugees so far in 2018. “[In Myanmar] the situation is really difficult and it has become complicated for us to move. It’s impossible to work or even to go to the market to buy food,” says Subi Katum, aged 70. Newly arriving Rohingya bring harrowing accounts of villages being burned down and relatives being killed or, ongoing violence, harassment, widespread destruction of villages and livelihoods. “My husband was killed and my daughter’s husband disappeared,” says Subi. “Many people have been killed or are lost. I hope all of this will finish one day but I can’t tell what the future holds.”

MSF has been working in Bangladesh for 25 years. Since 2009, MSF has run a health facility near Kutupalong makeshift settlement for Rohingya refugees and the local community. In response to the recent influx of refugees, MSF significantly increased its activities, expanding its operations to include additional medical facilities and water and sanitation. Elsewhere in Bangladesh, MSF works in Kamrangirchar slum in the capital, Dhaka.