Six years after an unprecedented exodus of Rohingya people from Myanmar to Bangladesh, medical needs in the world's largest refugee camp remain pressing and care increasingly inadequate.

In a global context marked by multiple large-scale humanitarian crises, international funding allocated to the humanitarian response for these one million stateless people is under increased pressure year on year. A very worrying situation for these people, who rely almost entirely on humanitarian aid due to their lack of legal status, which prevents them from working legally to sustain themselves or their families.

Despite being one of the largest healthcare providers in the camps, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has reached capacity in several areas, and we are now obliged to set stricter admission criteria to cope with the overwhelming medical needs of patients coming to our facilities.

We are therefore calling on international donors to significantly scale up their financial contributions to provide adequate support and prevent further irreversible consequences on the physical and mental health of Rohingya people.

Funding must be scaled up

Six years after the exodus

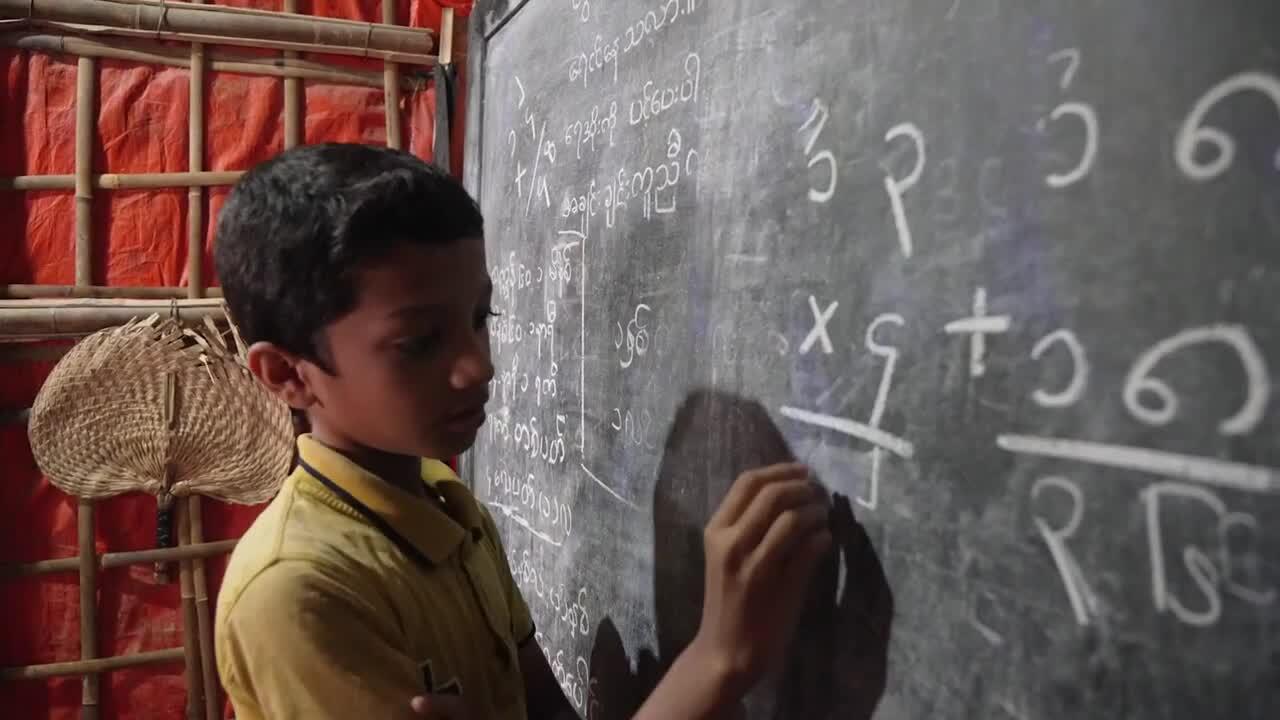

In just a few weeks in August 2017, more than 700,000 men, women and children fled the mass violence perpetrated against them by the Myanmar military in Rakhine State in northwestern Myanmar. They found refuge in the hills of Cox's Bazar district in Bangladesh.

The Bangladeshi people organised the reception of their neighbours, as they did on previous occasions. Six years later, what was a temporary solution to offer refuge to people escaping harrowing violence, has become a protracted crisis with no meaningful solution on the horizon.

Although the camps now have better roads, more latrines and drinking water than at the initial peak of the emergency, people still live in overcrowded shelters, and the construction of permanent structures is not allowed. Fires have destroyed hundreds or thousands of shelters, presenting an ongoing, but preventable risk to the safety of people living in the camps.

As the area is prone to natural disasters, shelters made of bamboo and plastic sheeting are often damaged and destroyed by strong winds, torrential rains and landslides. Added to this environment of extreme vulnerability is the impossibility of evacuating the camps to safer areas, as was the case during Cyclone Mocha in May this year. Most of our hospitals had to close for two days, their semi-permanent structures threatening to collapse.

Less and less funds reach the world’s largest refugee camp

For the time being, the return of Rohingya refugees to Myanmar remains a dream: they need guarantees of their rights, including recognition of their citizenship and a return to homes on their land.

Time seems to stand still. Life in the camps feels like a never-ending day. Camps have been surrounded by fences and barbed wire since the outbreak of COVID-19. Rohingya people are not allowed to work or leave the camps. Access to food, water and healthcare for one million stateless people depends on international humanitarian aid.

But aid is increasingly under-funded by international donors. Over the past two years, the commitment of UN member states to the humanitarian funding appeal has been dwindling: from around 70 per cent in 2021 to 60 per cent in 2022, and around 30 per cent so far in 2023https://fts.unocha.org/appeals/1082/summary. In March, the World Food Programme’s food rations were cut from the equivalent of US$12 per person per month to US$10, and then again to just US$8 in June.

Our teams witness difficulties faced by health centres run by various organisations dependent on this funding for human resources, drug supplies and the ability to ensure patient follow-up. Regular maintenance of water and sanitation infrastructure is also a challenge, making hygiene conditions and access to drinking water problematic in many camps.

Reflection: Rohingya six years on

Growing medical needs strain services

Unsanitary living conditions complicate the health situation considerably, leading to various health issues. Last year, patients with dengue fever increased tenfold on the previous year, and at the start of 2023, we saw the highest weekly increase in patients with cholera since 2017.

Forty per cent of people living in the camps suffer from scabies, according to the results of a long-awaited survey presented by the camps’ health sector coordination in May. This is well above the World Health Organisation’s recommended threshold of 10 per cent to start a mass drug administration for scabies outbreaks.

This situation has put an increasing strain on MSF’s services over the past two years. Our teams have been treating the consequences of difficult living conditions since the influx six years ago: infectious diseases, respiratory, intestinal and skin infections. But over the years, we have also seen a growing need to treat long-term illnesses linked to a chronic lack of access to healthcare for the Rohingya in Myanmar, such as diabetes, hypertension, or hepatitis C.

The number of patients arriving at the outpatient department of the ‘hospital on the hill’, built by MSF in the middle of the camps in 2017, increased by 50 per cent during 2022. This situation goes hand in hand with several health centres closing in the area in the past year due to a lack of funding and a rampant scabies epidemic.

In this hospital as well as in our mother-and-child hospital in Goyalmara, we saw an unusually high rise of paediatric admissions from January to June 2023 compared to the same period last year. In July, while the annual peak season of medical needs was only just starting, our paediatric hospital admissions were at capacity.

How will patients cope?

MSF is not directly affected by the crisis in funding from international donors, but the capacity of our services to absorb the ever-increasing demand for care is reaching its own limits. The growing number of consultations inevitably puts pressure on our human resources, hospital bed management and drug supplies.

As long as the Rohingya in Bangladesh are contained to camps and trapped in a cycle of dependency on humanitarian aid, it is imperative that international donors significantly scale up their financial contributions to provide adequate support and prevent further irreversible consequences on their physical and mental health.