Around a year ago, 12-year-old Houssam was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes following health complications that led to him to be hospitalised.

“The news really scared us," says his father, Mohammed. "We didn’t know that this disease could affect children. We had wrong perceptions about diabetes and the way it's treated.”

Living with type 1 diabetes

Since then, Houssam has received comprehensive medical care at the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) clinic in Aarsal, north Bekaa. This care includes medical consultations, treatment, and health education. Houssam was also given all the necessary tools to measure blood sugar levels and receive insulin injections. But for the past four months, his treatment has evolved.

Type 1 diabetes affects people at a young age and they often find it difficult to adapt to this lifelong chronic disease. One of the challenges faced is getting children and parents to accept that the treatment of this disease depends greatly on insulin injections and not on oral medications.

Patients with type 1 diabetes suffer from pancreatic insufficiency. This means the pancreas doesn’t produce enough insulin, preventing blood sugar (glucose) from entering cells and producing energy.

The disease also requires periodic monitoring of blood sugar levels, particularly as children affected by type 1 diabetes are more prone to sudden imbalances that can have serious complications and long-term side effects. MSF gives special attention to this category of patients and we are developing our programmes to better cater to their needs.

Good disease management, implemented by the children and their parents, and regular medical follow-ups can guarantee a normal life and the prospect of a bright future.

“I dream of travelling to Sweden to study to become a doctor,” says Houssam. “I’ve got used to living with the disease, and I’m now able to keep it under control with the help of my parents and the support of the medical team. The most difficult thing about it is not being able to have French fries whenever I want and having to take insulin with needles.”

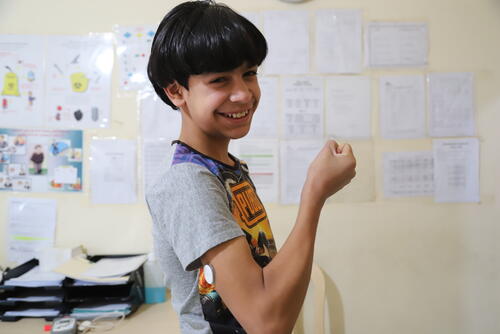

However, Houssam no longer uses the traditional measuring device that requires patients to prick themselves with needles to measure blood sugar levels. He was put on the continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) programme that MSF provides to 80 children in Lebanon. It is part of the chronic disease treatment programme for type 1 diabetes patients below the age of 15.

MSF has been adopting the CGM programme in our clinics in the Bekaa Valley and northern Lebanon since mid-2019. It is aimed at enhancing the quality of life of type 1 diabetes patients, empowering them, and increasing their level of adherence to treatment.

Patients wear a sensor on their arms to measure their blood sugar levels. The device has to be scanned at specific times during the day and night in order to save and display data in the form of graphs. This allows patients and parents to take immediate action and address sudden drops or spikes in sugar levels. It also enables the medical team to adjust the treatment programme during the medical examination on the basis of accurate data.

Twelve-year-old Cedra shares Houssam’s struggle with diabetes and the challenges of committing to a healthy diet. She often wishes she could eat sweets with her siblings and friends.

Cedra uses a different treatment technique - an insulin pen. MSF provides insulin pens to over 100 children in our clinics in the Shatila camp in south Beirut.

“We use the insulin pen with children and adolescents suffering from type 1 diabetes because it is more practical for them,” says Laura Rinchey, medical referent for MSF’s south Beirut project in Lebanon.

“Children or parents can adjust the insulin dosage with more precision and it is fast-acting. The objective behind this technique is to allow children to control their disease and manage their health on their own. This is the first step towards adapting to living with diabetes. Our health education and counselling teams work towards providing optimal support to children and communicating the necessary information to parents, thereby allowing them to cooperate and provide a healthy lifestyle to their children.”

Houssam will soon receive the insulin pen, which will spare him from having to use needles. MSF plans to implement this technique in our clinics in the Bekaa Valley. If our services weren’t available, Houssam and Cedra might not have received this quality medical care.

Cedra's mother says the family is suffering financially due to their refugee status and she is unable to afford the treatment and tools her daughter needs. The insulin, monitoring device, strips and insulin pens could cost up to 100 each month.

“I am sometimes unable to provide the healthy food recommended for my daughter, let alone the medication,” she says. “That worries me.”

Although being diagnosed with diabetes type I might come as a shock to the children and their parents, our medical teams praise their courage of their young patients. They say the parents now have increased awareness of diabetes and are doing a great job of adapting to the disease and protecting their children from its psychological repercussions and physical complications.