Adama has accompanied her heavily pregnant daughter, Mariam, to the MSF-supported hospital in Douentza, in central Mali’s Mopti region, so that she can give birth with the assistance of midwives. Adama and her daughter live out in the countryside, and the journey into the town was not easy.

“Since the crisis began, we are afraid of being robbed on the way,” says Adama. “We are afraid of having our things stolen, of being assaulted. Many people have lost their lives on these roads. If you are attacked by a robber and you don’t have any money, they’ll beat you up. The crisis has totally limited our freedom.”

Conflict crises in central Mali

The crisis Adama is referring to began in March 2012, with the north of Mali being occupied by non-state armed groups fighting against the Malian State and its military. In 2015, despite the signing of peace agreements, the crisis shifted to central Mali, which has increasingly become the focus of instability and violence within the country.

The activities of non-state armed groups in the Mopti region is not the only reason for the instability. In some areas it has combined with local conflicts between the Fulani community, who mostly make a living from livestock, and the Dogon community, who are mostly farmers.

Military operations have been ongoing in the Mopti region for several months, with the support of French and United Nations military forces, and the G5 Sahel . Malian military authorities have also imposed a number of public order measures, including curfews and a ban on travelling by motorcycle and two-wheeled pick-up vehicles.

Constraints limit access to medical care

All of these factors have combined to restrict people’s movements, making it hard for them to get medical care when they need it.

“It's difficult because we don’t have any health workers in the village and the nearest medical facility is 15 kilometres away,” says Ousmane, who has brought his five year-old son, Soumaila, to Douentza for treatment for severe malaria. “We made it to Douentza town in a cart,” he says.

Because of the violence and insecurity, many organisations providing healthcare, including public health providers and aid organisations, have either reduced activities or left the region completely, especially in those rural areas where the conflict is at its most intense.

Since the crisis began, we are afraid of being robbed on the way, of having our things stolen, of being assaulted… The crisis has totally limited our freedom.Adama Diarra, patient caregiver, Douentza hospital

Climate and conflict cause late arrivals at health centres

MSF teams have been working in Douentza since 2017 to ensure that some of the most vulnerable people can access free healthcare. At Douentza hospital, we have found that patients usually arrive with problems that have already become serious.

“Especially due to constraints related to insecurity, fear and distance, it is only when the patient’s state of health becomes very serious that they try to go to the health centre,” says Badamassi Abdrahimoune, MSF project coordinator in Douentza. “So we often have trouble treating these patients simply because they have arrived very late in the process.”

This experience is shared by our team supporting the hospital in Ténenkou, in the west of the Mopti region and near the Niger River. The river and its tributaries regularly flood during the rainy season, cutting off many villages and making travel almost impossible.

“The limitations caused by the prevailing insecurity today compound the chronic obstacles that rise during the rainy season,” says Frédéric Demalvoisine, MSF head of mission in Mali. “Every year between July and December, entire regions become even more isolated than usual, cut off from connecting roads because of the floods.”

We often have trouble treating these patients simply because they have arrived very late in the process.Badamassi Abdrahimoune, MSF project coordinator in Douentza

MSF teams take medical care to rural areas

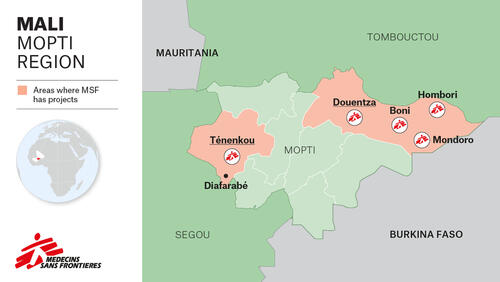

In response, MSF is sending our medical teams to reach those isolated populations cut off from health services. In the Douentza district, we have expanded our activities to three health centres in the rural areas of Boni, Hombori and Mondoro, where people are often prevented from travelling to Douentza by fighting.

From August 2018 to January 2019, our teams provided more than 21,800 medical consultations in these three locations. In the Ténenkou district, we run mobile clinics to provide basic healthcare and arrange for the most severely ill patients to be transferred to Ténenkou hospital.

MSF teams regularly travel to Diafarabé, south of Ténenkou, where hundreds of displaced people have settled since last November following an armed attack on the village of Mamba. Some 11 people were reportedly killed in the attack.

Kassé Tiouté is one of those who fled to Diafarabé; she recalls the events of November: “One day, armed men came to the village and killed 11 people. Many people fled immediately. We ran to Diafarabé. I was with my child, my mother-in-law and my sisters. We all fell ill. Even today, I am still fearful because of what we experienced. During the night, I see the same scenes all over again. I no longer want to go back to my village.”

Looking ahead, the humanitarian challenges remain enormous and we plan to continue to reach out to isolated people deprived of healthcare by the deteriorating security situation.