Interview with Cristina Carreño, MSF mental health advisor, on the role of mental healthcare for children in MSF’s programmes for victims of violence, conflict or natural disasters, and notably for displaced populations.

How prevalent are mental health disorders among the children and adolescents treated by MSF?

Let’s say first that it’s a general and worldwide issue: children and adolescents, as much as adults, have mental health disorders. Some are disorders that start in childhood and will develop into adult life.

More than 50 per cent of mental disorders start during the teenage years but very often they go undetected.

Some disorders or mental problems are linked to medical conditions, like malnutrition or HIV. Others are linked to an exposure to external events that children have difficulty coping with, such as violence, war, natural disasters, becoming separated from parents or close relatives or having them disappear.

Due to the nature of MSF’s work and the contexts in which we operate, these mental health disorders and problems are often present in the children our teams assist.

Do children experience trauma differently to adults?

Children experience the world differently from adults and express their feelings – their pain – in different ways.

Very young children see and experience the world through their main caretakers, who act as their mediators. They feel and reproduce the emotions of their parents and, if the family is going through difficult times, they will feel it, even if they don’t understand what is going on.

The expression of pain also depends a lot on the age of the child and his or her cognitive development.

Faced with the same trauma, different children react in different ways. Some will cry; others will isolate themselves; others will experience sleeping problems such as nightmares, fear or bedwetting.

Adolescents react in different ways too: they may isolate themselves, become aggressive, indulge in risky behaviour or avoidance, experience problems at school, or sometimes take on adult responsibilities.

Mental healthcare for children in Diffa, Niger

What is the role of parents and caretakers when providing mental healthcare to children and adolescents?

It is important that parents and caretakers are involved, as they are the mediators between the children and the world.

Unfortunately, in the conflict and emergency situations where MSF works, these caretakers, if they are not absent (having been killed or forcibly disappeared), have often themselves been exposed to extreme situations, and sometimes also suffer from mental health problems or disorders. And that can prevent them from playing their role.

This is why, when we identify a child with a mental health problem, we assess the whole family.

Partly this is to understand the dynamic around the child and the support available from close relatives, but it is also to check if other family members with mental health conditions might have gone undetected.

The child brought to an MSF clinic is sometimes not the most affected family member, just the one with the most obvious symptoms.

We help parents and caretakers understand what is going on with the child and how they can help by spending time with them, sharing activities and play, explaining what is happening, and helping the child to recover trust in the environment.

What techniques does MSF use to provide mental health support to children?

We use different techniques, according to the child or adolescent’s main problems.

For young children with malnutrition, it can take the form of massages and psychosocial stimulation activities.

Stimulation activities aim to reinforce the bond between child and caretaker and to stimulate the child’s senses; they are performed either by a caretaker or a health worker.

Playing is also a great way to stimulate children. In many of our projects, as in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Iraq, we have ‘children’s corners’ where children and their caretakers spend an hour each day playing and doing psychosocial stimulation activities.

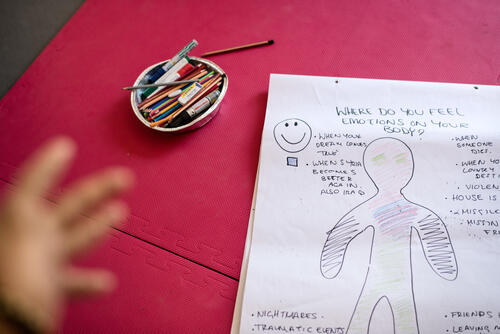

Drawing is also a tool we use, especially for children who have experienced potentially traumatic events in conflict situations.

While talking therapy works with adults, it’s not suitable as the main technique with children, as often they don’t have the words to express what they feel. So we play with them and also ask them to draw.

The drawings can be about what happened to them or their family, or about their nightmares. Afterwards, we can use the drawings to understand how the child is feeling and what he or she understands about what has happened.

The drawings can also be modified to help treat nightmares: we help the children change their drawings over time into something more positive so as to decrease their fear.

When helping adolescents cope with the consequences of trauma, we generally use talking therapy.

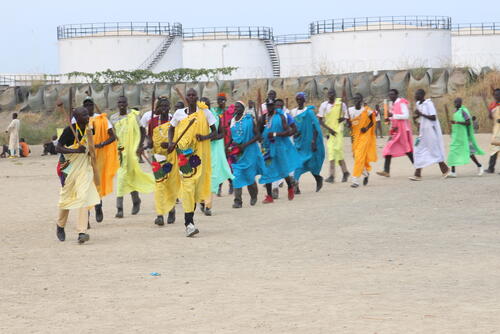

MSF mental health programmes also use community-based psychosocial activities to help children and adolescents develop resilience and coping strategies.

What are the main challenges MSF faces in providing mental healthcare for children?

First of all, there is a shortage of specialists in children’s and adolescents’ mental health. There is also stigma towards people affected by mental health issues, and children and adolescents in need of mental health support often go unrecognised. These challenges are not confined to the countries where MSF works.

Also, children in some societies are not considered to have their own voices, their own suffering. Their parents or their caretakers always talk on their behalf.

So we sometimes have to take children into a private and confidential space so they can express themselves – in agreement with their parents, of course. Involving the caretakers in the child’s therapy is usually a challenge, too.

In extremely violent contexts, teenagers and children often carry a heavy burden. In South Sudan, where MSF provides care to former child soldiers, these children feel guilty about what happened – about the actions they committed on the orders of adults.

They have a tendency to reproduce the violence they have seen around them for so long, both in their relationships and while playing. It takes MSF teams hours and hours of dedication to bring these children back to something approaching a child’s normal life.

Finally, our teams also see a lot of sexual violence against children and adolescents, the majority from within their own family, as is the case worldwide.

In some countries, this remains a taboo topic, which makes identifying, taking care of and protecting these children even more difficult.

Where possible, we try to talk with family and community leaders to help them. But MSF teams can be faced with difficult dilemmas in places where there are no shelters for victims, no protection mechanisms and no respect for law, and where you know that further abuse will happen once these children go home.

These are some of the reasons why we are reinforcing our mental health and psychosocial programmes for children and teenagers, and building up the capacity of our psychologists and medical staff to care for these young minds.