Interview with Miriam Alía, MSF vaccination and outbreak response advisor, on the outbreaks of meningitis C and measles that have affected Niger in 2018.

Why have these outbreaks occurred?

For another year running, Niger is facing several outbreaks of meningitis C and measles, two life-threatening and highly contagious diseases. Although both can be prevented by vaccines, the problem is different in each case.

For meningitis, there is no cheap and effective vaccine for all types of the disease, and the scarcity of production around the world means that vaccines can only be used reactively when an epidemic is declared. Vaccination against measles, on the other hand, has been included in routine vaccination programmes since 1974, but these programmes are still not reaching enough people to prevent the disease from spreading.

We have seen widespread meningitis C epidemics in the region in recent years. Has the situation improved at all this year?

It has been a fairly quiet year in the area known as the African meningitis belt, but there are still major shortages of meningitis vaccines. The International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision – the body that manages the vaccines – established a minimum stock of five million for meningitis C this year. However, we continue to vaccinate only when the epidemic threshold is crossed. Vaccinating as soon as the alert level is reached, as a preventative measure, would be more effectiveThe standard alert and epidemic thresholds are, respectively, 3 and 10 cases of meningitis per 100,000 inhabitants, per week..

Why is there a shortage of vaccines for meningitis?

There are different types of meningitis – serogroups A, B, C, W135, X and Y – and there is no effective vaccine for them all. For now, the best vaccine we have is tetravalent conjugate, which is currently effective against the four most common serogroups. But this is very expensive. The Serum Institute of India is working on a pentavalent conjugate vaccine (against meningitis A, C, Y, W-135 and X) which, in theory, will be inexpensive, effective and safe. But it will not be available before 2020. And given the prospect of having a vaccine capable of covering all needs, the rest of the laboratories are not investing in producing other vaccines in case they don’t sell them all.

How has the response to the meningitis C epidemic been in Niger?

Together with the Ministry of Health, we have vaccinated more than 30,000 people against meningitis C in the Tahoua region. We have also provided further support for patient treatment. We were surprised to find such a high percentage of cases of serogroup X, for which there is no vaccine at present. This is a major concern for the future.

Are there other prevention strategies for meningitis C?

New prevention strategies have been tested, such as the administration of a dose of an antibiotic called ciprofloxacin. This has been done in Niger. It seems that when administered to everyone in a rural area, transmission is considerably reduced. More studies are planned in the future to assess the impact of this strategy in urban areas. It could be another weapon in the fight against new epidemics, especially if they are not big.

And in the case of measles, why doesn’t routine vaccination stop the outbreaks?

The vaccination schedule is very strict in terms of age. In Niger, the national protocol states that children must be vaccinated up to 23 months old. But the vaccines provided by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, are only enough to cover children under 12 months old.

It should also be taken into account that a significant number of people in Niger live in nomadic communities or in areas affected by conflict. This means that they have little access to the vaccination packages offered in health centres. In order to prevent the spread of measles, vaccinations must reach a minimum of 95 per cent of the population. These coverage rates are difficult to maintain in such contexts.

How could the coverage rate be improved?

The children's schedule should be more flexible. Campaigns should include children up to five years old, and any time a child comes into contact with the health system should be an opportunity to update their vaccination card.

Multi-antigen campaigns should also be carried out to protect children from as many diseases as possible. We are currently responding to a measles epidemic in Arlit (Agadez). In addition to vaccinating against measles, we are taking the opportunity to administer the pentavalent vaccine and the pneumococcal vaccineDiphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) and hepatitis B. in the same campaign.

Where possible, and where vaccines are available, we are also vaccinating pregnant women and women of childbearing age against tetanus. This vaccine requires five doses and most women in contexts such as Niger do not receive all of them. So we are taking this opportunity to provide them and their future newborns with good protection. We should take every opportunity to vaccinate against deadly diseases.

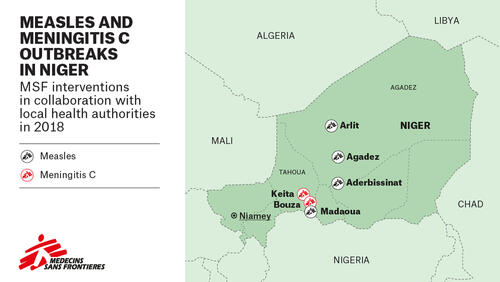

Since the beginning of 2018, MSF, together with the Ministry of Health, has vaccinated more than 179,460 people in Niger. This includes 145,843 children between six months and 15 years, who were vaccinated against measles in nine health areas in the Tahoua and Agadez regions.

A further 33,620 people aged between two and 29 years have been vaccinated against meningitis C in three health areas in the Tahoua region.

At present, MSF is carrying out a vaccination campaign against measles in Arlit (Agadez), with the aim of vaccinating more than 50,000 children under five years of age. Of these children, those aged under one year will also receive pentavalent and pneumococcal vaccines.