In the makeshift settlements in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, many Rohingya women give birth in their tents, limiting their medical options in case something goes wrong. MSF’s new maternity ward in Kutupalong, which will be able to withstand extreme weather, offers private rooms for new mothers and their babies, who face an uncertain future in Bangladesh.

A dazed woman sits on a green bed. She looks as if she has just run a marathon, but with none of the euphoria. She has just given birth to a 4.1-kg boy – a record weight for this delivery room. A midwife places the newborn baby in her arms and she puts the child to her breast.

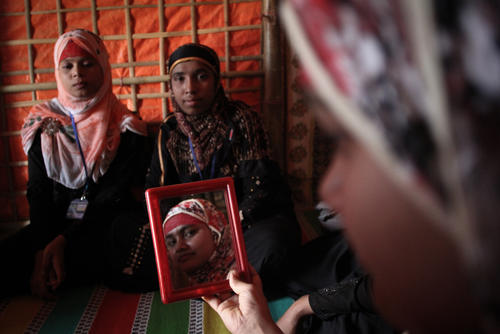

“In other countries where I’ve worked with MSF, women in the maternity ward visit with those in neighbouring beds, but not so much here,” says Yvette, who manages activities in the maternity ward in MSF’s Kutupalong hospital, just across the road from the entrance to what is now the biggest refugee encampment in the world. “Here they keep to themselves, cover their heads or faces with scarves and are unusually quiet.”

This young woman is in the minority in opting to give birth at hospital, as it is thought that about four in five Rohingya women in Kutupalong currently give birth at home. “I’m a big fan of home deliveries,” says Yvette, who comes from the American northwest, “but in this case, conditions at home are not ideal.”

Home for most of the refugees in Kutupalong, as well as the other makeshift camps in Bangladesh’s Cox’s Bazar region, is a loosely woven bamboo hut with an earth floor and a roof of tarpaulin or ragged polythene. Water has to be hauled from the nearest pump, and the communal latrines are often overflowing. “It’s not a nice place to live, let alone to labour and deliver in,” says Yvette.

Complicated deliveries

For those women delivering at home, options are limited if something goes wrong. At night the camps are unlit and the steep, narrow paths are slippery underfoot. Precarious bridges pass high across swamps and muddy streams. With few roads in the congested camps, an ambulance ride involves perching on a plastic chair strapped to two bamboo poles carried on the shoulders of two wiry youths.

And so women with complications in labour usually stay where they are at night. “By the next day, often they are in really rough shape,” say Yvette. Or they may bleed at home for days and then arrive at the clinic with sepsis.

“We also receive women after long labours at home when the delivery of the baby has become obstructed,” says Yvette. This can result from women taking synthetic oxytocin to induce or speed up labour at home. Readily available within the camps, oxytocin can backfire when taken in the wrong doses, causing life-threatening maternal complications, foetal death or fistulas.

Uncomplicated births are the exception in Kutupalong hospital, rather than the rule.

“It’s rare that we see a normal delivery here,” says Yvette. “Generally I only see critical cases – this feels more like an emergency room than a normal delivery room.”

Sexual Violence

Three of Yvette’s team of midwives, including Roksana work exclusively with survivors of sexual violence. Roksana oversees a team of 50 Rohingya volunteers – mostly young women in their late teens – who go from house to house in the camps, letting girls and women know that medical and psychological assistance is available for sexual violence survivors. A phone hotline set up by MSF also provides information about where to go for help.

The stigma associated with sexual violence means that survivors run the risk of rejection by the community if their experiences are made public. For protection, they are given a confidential password and a card with a special symbol to identify themselves to MSF’s medical staff.

“When the influx started, lots of people came to us saying: ‘I was raped by the military or Rakhine people – what can I do?’” says Roksana.

Almost nine months after the latest violence in Myanmar, rape survivors are still coming forward.

“They still come every day,” says Roksana. “Often they don’t want to share their stories at first, and I have to encourage them to talk. I give them psychological first aid. I tell them: ‘It’s not your fault, don’t be afraid, we’re here to help you.’”

The help on offer includes mental health support, medical assistance and referrals to specialist agencies, where necessary.

Organisations offering specialised services play an important role in helping women and girls who are pregnant from rape find a safe and secret place to spend the last months before giving birth at MSF’s hospital. If the mother is unable or unwilling to keep the baby, she may also need help finding foster parents.

Other rape survivors choose to terminate their pregnancies out of desperation – often unsafely and at risk to their lives. Medication to induce abortions is easy to get hold of in the camps, but usually without instructions for its use. “Used in the right way, these drugs are the safest option,” says Yvette. “Used in the wrong way, they pose risk of heavy blood loss and severe infection. We’ve seen maternal deaths following unsafe abortion practices.”

The old maternity ward in Kutupalong, crowded with beds and divided by rickety bamboo partitions, offered little privacy for women and girls in such desperate circumstances. But MSF’s brand-new maternity centre next door, with private rooms for rape survivors, allows them the dignity of being cared for in confidence, without being overheard or identified.

The new maternity centre, sturdily built of concrete, metal and bricks, will also be able to stand up to extreme weather – an important consideration in a region lashed by monsoon rains and cyclones. It is part of an ambitious plan to reconstruct MSF’s entire hospital in response to the medical needs of both the refugees and the local community.

Born into an uncertain future

Statistically, of the 10 beds currently occupied in the maternity ward, five women are here because of medical emergencies – eclampsia, post-partum haemorrhage, sepsis. Four women are here because they were raped. Just one of these 10 women is likely to have a normal delivery.

But even those babies born without complications will have little chance of leading a normal life. They will have few of the rights taken for granted elsewhere. Since last year, the births of Rohingya babies in Bangladesh have not been registered. The Rohingya children born here will have no birth certificates, no refugee status, no citizenship. They will have no formal education and no employment opportunities and their freedom of movement ends at the checkpoint just north of the camps.