The Palestinian enclave of Gaza has been blockaded by Israel for more than a decade, during which time its people have witnessed three wars and other frequent outbreaks of violence. The economy is in freefall and the humanitarian situation continues to deteriorate. Israel only permits a small number of people to leave, and since the border with Egypt is also frequently closed, people feel – and in effect often are – trapped.

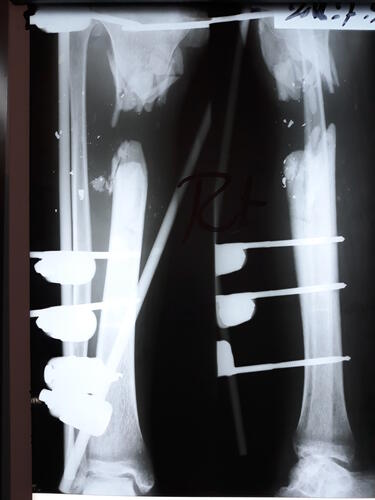

‘The Great March of Return’ protests held at the border almost every Friday since 30 March 2018 have been met with hails of gunfire from the Israeli army. By the end of 2018, 180 people had been shot dead and 6,239 injured by live fire – the vast majority sustaining wounds to the legs. It is these complex and severe injuries that our teams have been struggling to respond to.

How do you treat thousands of similar injuries, all needing multi-stage treatment, potentially lasting for years? Marie-Elisabeth Ingres describes what she saw in Gaza in 2018.

"We were not prepared for what happened. We had been watching every rocket launched from Gaza, every assassination and bombardment, wondering if it would trigger a new war, one even more violent than that of 2014. However, we had not envisaged the number of people who would be shot during the March of Return protests. These protests have turned into bloodbaths, occurring with such relentless regularity, month after month, that we have become almost used to them.

30 March 2018: we were stupefied when we learned that more than 700 people had been injured and 20 killed by live fire from Israeli soldiers stationed at the fence that separates Israel from Gaza. From that moment, a machine was set in motion to respond to the huge needs and since then it has not stopped. Friday after Friday, hundreds of patients with bullet injuries have been treated in Ministry of Health hospitals. Half of those injured have ended up in our clinics for post-operative care.

Our teams in the field have worked tirelessly to increase our capacities, rapidly scaling up recruitment and training. We brought in surgeons, anaesthetists and other specialists to treat the mass influxes of wounded patients; nevertheless, our facilities struggled to cope and were quickly overwhelmed by the number and the severity of the injuries.

Along with the other humanitarian organisations in Gaza, we had to quickly prepare for 14 May, because of the numerous calls to protest against the inauguration of the American embassy that day in Jerusalem. It was a black Monday, a day of war. It reminded our traumatised Palestinian colleagues of the 2014 war.

For me, it brought back memories of 5 December 2013 in Bangui, Central African Republic, when the anti-Balaka attacked the city: the bodies that arrived in the space of a few short hours; the overwhelmed teams; the horror in the face of tragedy.

In Gaza, from that Monday on, the machine went into overdrive, and except for a few lulls, there has been no let-up. Every week there are new patients, many with open fractures, at risk of infection, that will require months, if not years, of medical care, surgical procedures and rehabilitation. Some will be disabled for life.

All of this has occurred in a blockaded territory where the health system was already unable to provide adequate care for everyone. The injured of Gaza have largely been abandoned simply because of where they were born.

The young Palestinians that we see in our clinics feel hopeless, as though they have no future. Of course, some may have been manipulated by the authorities into protesting along the fence. Or they may have been simply protesting against an unjust life and a lack of liberty. Laws, personal freedoms and human rights are disregarded by all sides. Millions of people have become mere pawns in political games in which they have little say.

Today, our teams continue to do all they can to treat these young men’s wounds and prevent the loss of their limbs, although we know that we will be able to heal only a small proportion of them because of the constraints imposed by the Israeli blockade and the various Palestinian authorities.

We feel a sense of dread at each moment of tension, as we wait to see if Gaza will erupt once again into war, as it did in 2014. If it doesn’t, perhaps we will be able to envision addressing the complex medical needs – including treatment of bone infections, reconstructive surgery and physiotherapy – of some of those who have been crippled by their injuries before it is too late.

Expert surgeons, antibiotic specialists and a new laboratory able to analyse bone samples are required to deal with severe wounds such as open fractures. We are doing all we can to find these people and resources, both in Gaza and abroad.

The situation in Gaza poses many human, technical, logistical and financial challenges for us, but we are committed to providing the best response possible. We will not give up, even if we do not have the resources to manage right now and the political context is not in our favour, with people’s medical needs falling to the bottom of the authorities’ agendas. We are struggling, but if we save even a few young people, we will have succeeded."

Mohammed's story

"I was injured during the ‘Great March of Return’ protest on Friday 6 April. I knew it was dangerous, but I went anyway – everybody did. I was just standing there when I got shot. I felt the bullet shattering my bone.

I’ve had six operations so far, including debridement operations [cleaning the wound of damaged tissue and foreign objects] and an operation to close the wound. Then I was told I might need to undergo an amputation after closing the wound.

At the start, I was coming to the MSF clinic daily to receive treatment. Now I go three times a week for physiotherapy and to have the dressings changed on my leg. After receiving physiotherapy, I feel better. The spasms decrease and moving my muscles is easier.

Why was I protesting? I am like every Palestinian – we have been through a lot of conflicts with Israel, and it is never-ending. I went to protest at the border because it is our right and this is our land. I went there only for this purpose.

I haven’t been back. I can’t move. I stay at home. I sleep for a few hours and then I’m woken by the pain. If I can have my leg back as it used to be, then maybe I can go back to work and have a future.”

MSF physiotherapist Abu Hashim explains Mohammed's injury

“Fractures like Mohammed’s occur after high-impact trauma and considerable force," Abu Hashim, MSF physiotherapist in Gaza, explains. "The soft tissue has been destroyed and the bone shattered. He has also had a skin graft. But the most complicated thing about Mohammed’s injury is that his common peroneal nerve is completely cut, making his foot drop – meaning he is not be able to walk properly and could be disabled for life. The physiotherapy is very painful for him, but vital to avoid joint stiffness and to move the muscles.”