334,300

334,3

60,200

60,2

41,300

41,3

26,900

26,9

15,400

15,4

12,800

12,8

By the end of the year, 1.9 million people were internally displaced and 7.7 million were in need of humanitarian assistance in northeast Nigeria.<a href="https://reliefweb.int/report/nigeria/north-east-nigeria-humanitarian-situation-update-progress-key-activities-2018-8">UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs</a> and <a href="https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/nigeriasituation#_ga=2.180696423.1358997199.1543419016-1271149834.1543419016">UNHCR</a>

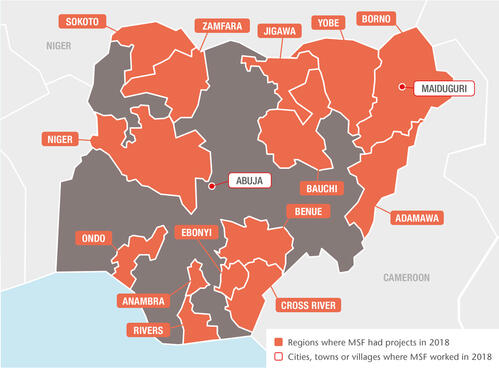

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) continued to assist people affected by the violence in Borno and Yobe states throughout 2018, while maintaining a range of basic and specialist healthcare programmes and responding to other emergencies across the country.

Vital medical assistance in the northeast

Almost a decade of conflict between the military and non-state armed groups have taken a heavy toll on people in northeast Nigeria. Many thousands have been killed or have died of malnutrition and easily treatable diseases such as malaria due to a lack of healthcare.

MSF and other NGOs have been working to fill gaps in services, but their access is frequently hampered by insecurity. According to the United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, there were up to 230,000 people newly displaced in the last quarter of 2018 alone, and 800,000 remained out of the reach of aid organisations.

Assistance is mostly concentrated in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno state, which hosts one million displaced people, but even here, services remain inadequate.

Outside Maiduguri, people living in towns or enclaves controlled by the military are unable to farm or fish, due to restrictions on their movements. And humanitarian assistance cannot be delivered to people living in areas controlled by non-state armed groups.

We have teams in various locations around Borno and Yobe states, supporting emergency rooms, operating theatres, maternity and paediatric wards and other inpatient departments, carrying out nutrition programmes and vaccination campaigns, and offering mental healthcare, reproductive health services, support to victims of violence, including sexual violence, and HIV testing and treatment.

We also support emergency referrals to Maiduguri, and monitor food, water and shelter needs among the displaced.

In 2018, we ran fixed primary healthcare facilities in Maiduguri, Ngala, Rann, Banki and Pulka, secondary healthcare facilities in Pulka and Gwoza, and paediatric hospitals in Maiduguri and Damaturu, as well as in Monguno, until activities were handed over in July, and in Bama as of August. We also ran mobile clinics on an ad hoc basis in Gajigana, Gajiram and Kukawa.

During the year, our teams conducted over 247,400 outpatient consultations, assisted more than 5,000 births, treated 15,700 children for malnutrition and 27,400 people for malaria.

Emergency response to disease outbreaks and displacement

In March, in response to one of Nigeria’s largest ever Lassa fever outbreaks, we sent a team to support the 700-bed federal teaching hospital in Abakaliki, Ebonyi state.

We improved infection prevention and control measures, strengthened surveillance and case notification systems, and provided clinical management and operational research to help tackle this poorly understood and neglected viral haemorrhagic disease. We also supported Akure general hospital and nine health centres in Ondo state during the epidemic.

We responded to cholera outbreaks in Borno, Yobe, Adamawa, Bauchi and Zamfara states, treating a total of 26,900 people. We supported the Ministry of Health to implement an oral cholera vaccination campaign in Bauchi state, and vaccinated 332,700 people in Borno and Yobe states.

As political violence escalated in Cameroon’s Southwest and Northwest regions, more than 30,000 people fled into Nigeria.

In June, we launched an emergency intervention in Cross River state to provide medical care and clean water to refugees and host communities. By the end of the year, the teams had conducted over 7,100 medical consultations.

In neighbouring Benue state, hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced by interethnic conflict over natural resources. In February, we responded by setting up healthcare services in Makurdi, Logo and Guma camps, and conducting water and sanitation activities.

Healthcare for women and children

Reducing maternal and neonatal mortality is a priority for MSF throughout the country. As well as running paediatric hospitals in Maiduguri, Damaturu and Monguno, then Bama, in the northeast in 2018, we continued to provide comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care in Jahun general hospital, Jigawa state.

In 2018, 63 per cent of the 16,000 pregnant women admitted to Jahun hospital had complications. A specialised team performed 267 vesico-vaginal surgeries on women with obstetric fistula, a condition resulting from prolonged or obstructed labour. Basic emergency obstetric and neonatal care is also available at three heath centres we support in the area.

We have teams working in two clinics in Port Harcourt, offering medical care and psychosocial support to an increasing number of victims of sexual violence. Over 1,400 people were treated in 2018, 61 per cent of whom were under 18.

In December, we closed our project in Anambra state, where we had been supporting malaria testing and treatment in a primary health care centre and seven health posts in Okpoko township since November 2017.

In that time, almost 6,000 people were tested for malaria and 3,500 received treatment, including 2,900 in 2018 alone. The majority were pregnant women and children under five.

In Sokoto, we continue to support Noma Children’s Hospital, the main facility in the country specialising in noma, a facial gangrene infection that affects children in particular.

In 2018, our teams performed 150 surgeries on 117 patients, as well as providing mental healthcare services and community outreach, surveillance, awareness-raising and health promotion.

Since 2010, we have also been treating children aged under five for lead poisoning associated with artisanal gold mining in Zamfara state. Our teams work in the 99-bed paediatric ward of Anka general hospital and in five outreach clinics in the surrounding area.

In 2018, we treated around 800 patients a month. We set up a similar project for lead-poisoned children in Rafi, Niger state, in 2015. This was handed over to the national health authorities midway through 2018.

MSF and the Ministry of Health organised two medical conferences in 2018, one on noma, the other on lead poisoning, in both cases to raise awareness and increase government attention, with a particular focus on prevention.