Karam Yaseen works as a health promoter at MSF’s comprehensive post-operative care facility in East Mosul, Iraq, where almost 40 per cent of patients arrive with multidrug-resistant infections.

Every day, he talks to patients and their caretakers about health issues and promotes healthy behaviour. He also runs awareness sessions about the use of antibiotic drugs.

Karam describes how the misuse of antibiotics can have a dramatic impact on the health and recovery of patients, many of whom have infections that are resistant to treatment with antibiotics.

Antibiotic resistance has not always been a major problem in Iraq. Fifteen years ago, the use of antibiotics was fairly well regulated and we had a good medical system.

But the war in 2003 changed everything. After that, some antibiotics that require a prescription became very easily accessible on the market and people started to use them more and more, whenever they were sick.

Now, in Iraq, a pharmacist can sell you antibiotics, even the injectable ones, without a prescription.

The availability of these drugs is directly linked to the patterns of resistance that we see today in bacteria, and it explains why a lot of the patients that we treat suffer from antibiotic resistance.

The consequences of antibiotic resistance

More than a year after the military offensive on Mosul, the consequences of antibiotic resistance are more striking and more visible than ever.

A lot of people were wounded during the battle and violent trauma is always dirty. The risk of infection is generally higher for these patients, and they are more likely to take antibiotics to get better.

But the excessive use of these drugs over the years means that antibiotics no longer play the role they should. In concrete terms, it takes much longer for patients to recover from their injuries.

A simple wound that has not healed properly could mean that the infection has become chronic and that the bacteria are multidrug-resistant, requiring multiple surgical interventions and a longer antibiotic treatment regimen for the patient to heal.

More than one-third of our patients in East Mosul currently show a resistance to antibiotics.

Raising awareness of antibiotic resistance

We organise awareness sessions for patients and their relatives, to give them more information about these drugs. We explain the effect of each antibiotic on the body.

There’s usually very high interest from caretakers to learn more about this issue, because they have to take care of relatives who are suffering from this condition.

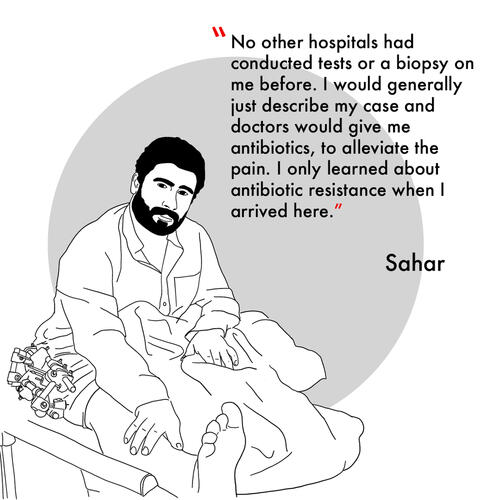

People ask a lot of questions to get more clarity on what antibiotic resistance really is. A lot of people are surprised by the information we tell them.

They realise that antibiotics are not always the magical solution to everything; that antibiotics should always be on prescription; and that misusing antibiotics can do more harm than good.

Usually, at the end of our sessions, people thank us because they feel much more informed about this issue.

They also tell us that they will spread the message and tell more people about it. That’s very important; because it takes the information we provide outside the facility and brings the conversation about antibiotics into people’s homes. This is what is needed if we want this practice to change on a countrywide scale.

Health promotion and patient support

As health promoters we also support people put on ‘contact isolation’. Patients infected with antibiotic-resistant pathogens usually have to be isolated from others and often cannot leave the hospital for long periods of time while they take their course of drugs prescribed by our infectious diseases specialist.

Accepting isolation is very hard for patients here. There’s a certain stigma associated with it: people may think that they have a contagious or dangerous disease.

That’s why it’s essential to give them more information about their condition and to explain to them why they need to be isolated. MSF also provides them with mental health sessions to help them deal with the emotions caused by this isolation.

For all these reasons, I see the role of the health promoter as essential – not only here, in East Mosul, but in every single medical facility across the country.

We need to provide information to patients and their caretakers; they need to fully understand the condition they have and the treatment they’re following.

This type of knowledge is crucial to a good recovery and to changing the situation on a larger scale.

Almost 40 per cent of patients admitted to our post-operative care facility in East Mosul between April and mid-November 2018 had a microbiologically confirmed infection. Of that 40 per cent, 90 per cent had an multidrug-resistant infection.

We have been working in and around Mosul since 2017 to provide lifesaving services for people caught up in the violence. Throughout 2017 and 2018, we ran a number of trauma stabilisation posts in East and West Mosul and worked in four hospitals, providing a range of services including emergency and intensive care, surgery and maternal healthcare. In April 2018, we opened a comprehensive post-operative care facility in East Mosul for people injured by violent or accidental trauma.