1,157,900

1,157,9

276,400

276,4

56,200

56,2

14,300

14,3

7,540

7,54

3,840

3,84

1,370

1,37

670

67

Healthcare is scarce or non-existent in many parts of South Sudan, with less than half the population estimated to have access to adequate medical services. Around 80 per cent of services are delivered by NGOs such as Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

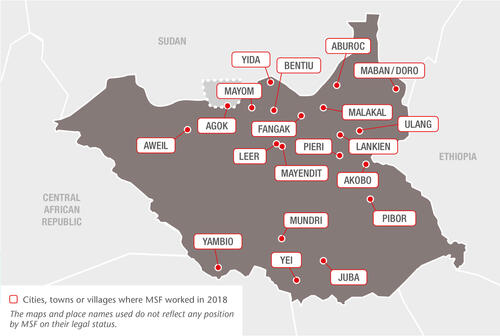

In 2018, we responded to the urgent medical needs of people affected by violence while maintaining essential healthcare services through 16 projects across the country, but as in previous years, direct attacks against healthcare staff and facilities repeatedly hampered activities in 2018.

Assisting displaced people and remote communities

In Old Fangak, a remote, swampy region in the north, we run the only secondary healthcare facility serving the many displaced people who have settled there. Our teams also travel by boat into the surrounding communities to run mobile clinics and organise hospital referrals, and we run community health posts in remote locations around Lankien and Pieri.

After an upsurge in intercommunal violence and displacement in Ulang, we started offering emergency and inpatient care in a local health facility, and referred patients with complications to Malakal and Juba.

Further north still, in Aburoc, we continued to support a 12-bed inpatient facility with emergency care, outpatient services and treatment for victims of sexual violence, while also treating common diseases such as diarrhoea and malaria at community level.

In the south, we support primary health centres in Yei and the state hospital’s paediatrics unit, which serve local communities and displaced people. We also have teams working in three facilities in Pibor, including a health centre with surgical capacity, we support a primary health centre in Mundri town and run community health posts in remote locations around Mundri.

In December, we handed over our mobile clinics in Akobo and a primary healthcare facility we built in Kier to other organisations. Working in hard-to-reach areas with no other medical services, our teams treated more than 50,000 patients and ensured several hundred referrals for secondary care between late 2017 and the end of 2018.

Protection of Civilians (PoC) sites

Protection of Civilians sites in South Sudan have been in operation for more than five years after people fleeing the conflict sought safety at existing UN bases. These sites afford a level of protection to vulnerable populations who would otherwise be exposed to armed violence outside them.

Poor living conditions, ongoing violence and mental trauma have created enormous medical needs in the country’s largest PoC site, in Bentiu. Our 160-bed hospital is the only provider of secondary health services inside the PoC, including surgery and specialist care for newborns and complicated deliveries.

In 2018, we treated 398 victims of sexual and gender-based violence in the PoC and in a clinic in Bentiu town. Nearly a third of all these cases occurred in a period of just a few weeks following an attack on women and girls in Rubkona county in November 2018.

We also set up six malaria treatment points and provided care to over 38,000 patients following a sharp increase in malaria cases in July.

In Malakal PoC site, which hosts about 29,000 people, we run a 40-bed facility offering emergency care, treatment for tuberculosis (TB), kala azar (visceral leishmaniasis), and HIV, as well as mental health services.

Our teams there documented an alarming rise in the number of suicide attempts in 2018, evidence of the consequences of long-term displacement, unemployment and limited prospects.

We also work in Malakal town, providing the same services as in the PoC, with the addition of neonatal and obstetric care, including for complicated deliveries.

Mother and child healthcare

At Aweil state hospital we run the paediatric, neonatology, maternity and burns wards, the emergency room and intensive care unit, and an inpatient therapeutic feeding centre. The maternity ward was filled to capacity in September; over the year our teams assisted 5,275 deliveries, including 174 by caesarean section.

Our 80-bed hospital in Lankien also provides obstetric and paediatric care, nutritional support and treatment for victims of sexual and gender-based violence, as well as treatment for HIV, TB and kala azar.

Supporting former child soldiers

Children have been used as soldiers all over South Sudan and efforts are now being made to reintegrate them into their communities.

In February, we started a pilot programme offering medical and mental healthcare to former child soldiers, 949 of whom were reintegrated into their communities in Yambio in 2018.

Responding to epidemics

We treated over 37,000 people for malaria through our project in Lankien in 2018, and scaled up malaria treatment in Aweil hospital in response to a seasonal peak.

Additionally, we supported the Ministry of Health in vaccinating nearly 23,000 children during a measles outbreak in Aweil, and in conducting a preventive cholera vaccination campaign that reached more than 200,000 people in Juba.

Sudanese refugees

In and around Maban, we assist Sudanese refugees and the local community through our activities in Doro refugee camp and support to Bunj state hospital.

We also continue to run a 15-bed inpatient department for refugees in Yida, but handed over our HIV/TB treatment programme to another organisation in May 2018.

Abyei Special Administrative Area (ASAA)

In Agok, we finished renovating and extending our hospital, the only secondary health facility in the area of disputed territory between Sudan and South Sudan.

We also resumed our community malaria project at the onset of the peak malaria season, treating over 25,000 patients in 23 surrounding villages between June and December, and referring severe cases to the hospital.

In response to displacement caused by severe flooding in an usually heavy rainy season, we sent mobile teams to the southern part of the ASAA to provide healthcare and distribute relief items.

Attacks on healthcare

In April, one of our mobile medical teams in Mundri was subjected to a violent armed robbery, which forced us to suspend all activities in the area for several weeks.

We also suspended all activities except essential lifesaving treatment in Maban following a violent attack on the MSF office and compound in July, but by mid-September we had returned to full capacity.

In Mayendit and Leer counties, thousands of civilians fled into the bush and swamplands to escape violent clashes in April and May. Our health facilities were also attacked and looted, but our teams continued to deliver basic medical care to the people they could reach.