00:00 – 00:28 Presenter: Ladies and gentlemen, good evening and welcome to a new episode of “Today’s Talk”. On this episode, we’re hosting Mr. Thierry Durand, MSF operations director.

00:29 – 00:46 We will talk about the uprisings and the controversy of the debate between the Sudanese Government and humanitarian organizations that were precluded, expelled, and deported from Sudan on the background of a gamble of power between the government and the NGOs.

00:47 – 01:03 It is understandable to kick off the talk with our guest, Mr. Thierry Durand, with this question

Why did you pull out of Sudan and what are your comments on the decision of the Sudanese authorities concerning the preclusion of NGOs?

01:04 – 01:23 Thierry Durand: We don’t understand it. We don’t understand this unfortunate and frightening decision, especially for the Sudanese in Darfur. I personally think that the accusation made to the NGOs, including MSF, is unfair.

01:24 – 01:38 A short while ago, they started to publicly describe us as thieves and spies in front of mass audiences, which is concerning for our own safety. These accusations are wrong! Completely wrong!

01:38 – 01:58 I understand the rage of the Sudanese President because of the arrest warrant issued against him by the International Criminal Court (ICC). These accusations are actually unjust; as if the NGOs, and particularly MSF, have fallen into a trap.

01:59 – 02:31 We became hostage of the current political game between the international community, the UN security council and the Sudanese government. We are an easy and sensitive scapegoat in my opinion. We cannot work unless the government allows it. We were expelled along with 13 other organizations. As you can see, this is tragic. These decisions are highly political.

02:32 – 03:01 Presenter: At the moment, could we say that no MSF members are still working in Sudan since the decision of preclusion, expulsion, and deportation was made or are some teams still working in Sudan? If yes, where are they working, and under what circumstances?

03:02 – 03:09 Thierry Durand: No, all the activities stopped. The activities are suspended completely and immediately. We had to leave the hospitals.

03:10 – 03:25 I particularly remember the Niartiti hospital, which was once a small village, located at the foot of the Marrah mountain. There are many refugees there. It is a crossroad for Bedouins, Arabs, and refugees from the Fur ethnic groups.

03:26 – 03:31 The government also allowed us access to areas controlled by rebel groups in the mountain.

03:32 – 03:43 There was an integrated health system that wasn’t available in the past. It’s not even included in the roadmap of the Ministry of Public Health. It is new and available thanks to MSF, however we had to leave.

03:44 – 03:53 All the doctors left, and the medical support as well. We had to leave patients behind in the hospitals. There was an outbreak of meningitis that was getting started in the country.

03:54 – 04:12 The Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), is an efficient ministry in Sudan, with competent staff who are excited to work. Some of the best doctors relied on us. They were our partners for about 30 years. There’s nothing we can do. Everything was taken away from us.

04:13 -04:20 Two teams have already left, and three teams remain, the Belgian, the Swiss, and the Spanish team.

04:21 – 04:32 However, as you know, following these declarations, three members of the Belgian team were taken as hostages. This is worrisome, especially when talking about continuing our operations.

04:33 – 04:44 We’re thinking of many questions that we would like to discuss while keeping all the communications channels open with the government directly, and not through foreign embassies or the UN.

04:45 – 04:58 This is why we speak to media outlets like yours. It’s because we want to keep these discussions alive. We hope that one day we’ll be able to resume our work in Sudan where we’ve been working for the past 30 years.

04:59 – 05:06 We love the Sudanese people. They are hospitable, open-minded, and indulgent. What happened is really sad.

05:07 – 05:43 Presenter: Mr Durand, the Sudanese government has the impression that you as a humanitarian organization and other activists working in the refugee camps have submitted hostile and exaggerated reports against it and have given misinformation about the humanitarian situation. These reports might have been used by the International Criminal Court and western governments to condemn, indict or accuse the Sudanese government of human rights violations.

05:44 – 05:59 Thierry Durand: If we go through the history of the war in Darfur, we find that the most violent period included a mass destruction of villages, people fleeing their homes, and a high number of casualties and crimes. Everybody knows this.

06:00 – 06:10 From August - September 2003 until April 2004, when the ceasefire agreement was concluded in N'Djamena, the period was frightening. This is the truth.

06:11 – 06:27 During this period, it was difficult to work in Darfur. It was a closed area. We were able to start working there. We were the first ones to work there since the end of 2003. We witnessed everything and reported it to the government.

06:28 – 06:50 Since the ceasefire agreement was concluded in 2004, the government allowed the provision of help in Darfur due to the UN pressure. Therefore, The UN and many other NGOs, including us, called for aid. We asked our colleagues from other sections to come, which resulted somehow in stabilizing the situation.

06:51 – 06:56 While we were afraid of the occurrence of famine and outbreak of epidemics, the efforts deployed by these organizations guaranteed that none of this happens.

06:57 – 07:05 We can say that the government did well at the time by allowing humanitarian assistance to reach Darfur.

07:06 – 07:26 In MSF, what we’ve been saying since this period has not changed. We said it to the government and shared it publicly. Since 2004, the situation in Darfur has not been dangerous in a general sense. It is a situation that includes 2.5 million people, which is a third of the region’s population and they are living in camps.

07:27 – 07:44 They completely rely on the provision of assistance, for food, water, hospitals, and education. There is a general reliance from the side of the population, but the situation isn’t tragic. The mortality rate is better than in many other regions in Sudan.

07:45 – 08:00 However, during this period, other pockets and locations were suffering from conflicts related to political clashes, tribal and local problems, and banditry, and all these factors were accumulating.

08:00 – 08:11 This is what we’ve been saying all along. We face significant access difficulties to reach these regions, for security reasons. This is due to the unsafety of the road and the thieves, etc.

08:12 – 08:24 It is true that other entities, such as human rights bodies – And here, we must distinguish between international justice and human rights activists and humanitarian organizations, as they are not the same.

08:25 – 08:36 These bodies made a lot of noise since 2003 and tackled many subjects, including genocide, war crimes, and justice, and called for the attainment of justice to the very end.

08:37 – 08:54 We are not the ones who are doing all of this, and neither are the independent aid organizations. It’s the doing of the activists, particularly human rights activists, bodies like the American Save Darfur and Darfur Emergency. This was happening with great media hype.

08:55 – 09:03 Such bodies may be doing their jobs, but it is not our role. It’s not. This is not our role.

09:04 – 09:23 I want to return to the subject of intimidation. There is something that shocked us a lot and shocked me in particular. It’s what has been said, especially by the deputy Mr. Ocampo on November 2008. He described in a statement at the UN the camps as death camps when he was talking about the situation of the displaced people in Darfur.

09:24 – 09:39 This is not true. If it was true, we would have said so publicly during the five years we spent working in the camps, and left the place as a strong public statement, but it’s not true.

09:40 – 10:06 A few weeks ago, Ocampo was saying that the death tolls were up to 5,000 death per month due to the war and the violence, which is also not true. Even the 2008 UN figures estimate that casualties amounted to 1800 to 2000. The difference is huge. We don’t accept this, and we’ve said it clearly before.

10:07 – 10:27 At MSF, we try to be as unbiased as possible. We sometimes face tense situations with the Sudanese government. This has happened repeatedly in the past, especially in the south, but we try to address these problems with the government directly.

10:28 – 10:44 I don't know, maybe Mr. Ocampo slipped up. We’re not looking to comment on the international judicial establishment, but maybe he himself has become an activist somehow.

10:45 – 11:06 Presenter: Do you think that the decision of the International Criminal Court to prosecute and arrest Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir negatively impacted you, and turned you, as international medical humanitarian organizations in Sudan, into scapegoats? Did it subject you to harassment and resulted in an estrangement from the Sudanese government?

11:07 – 11:30 Thierry Durand: Yes, because the Sudanese judiciary system, and the Darfur judiciary, in particular, is highly politicized. Everything becomes a political issue. There are the peacekeeping forces of the UN and the African Union UNAMID, the international justice issues, and the humanitarian issues, all of which are linked.

11:31 – 11:44 For us, staying away from this narrative and asking the parties to slow down, as everything is getting mixed up. We, the relief actors in the field, have a different role. This was difficult to achieve, even impossible.

11:45 – 11:56 Everything was mixed up. We can understand that the Sudanese president is defending itself and therefore it uses harsh terms that are unjust and incorrect.

11:57 – 12:10 You know that MSF was the only organization operating in the region. As I said before, we are present since the beginning, since 2003, during the most challenging period.

12:11 – 12: 21 We also said- when there were talks about genocides by the US and the human rights activists, we were the only organization that asked the parties to take it down a notch.

12:22 -12:37 We were present in Rwanda during the genocide. What we witnessed in Rwanda isn’t the same as what’s happening in Darfur. We won’t use the term genocide. What we saw in Darfur wasn’t a genocide, compared to what happened in Rwanda.

12:38 – 12:41 There’s no doubt that human rights activists have other definitions of the term.

12:42 – 12:58 Anyway, this is what we said based on our own experience. We said it clearly and publicly. We weren’t working or collaborating with the ICC. We discussed the matter with them in 2003, but it was general and didn’t focus on Sudan.

12:59 – 13:25 We try to work in conflict zones, and war zones and reach out to the people who are victims of these conflicts. We must be able to argue and convince the entirety of the soldiers, the rebel groups, even bandits, and sometimes the governments and armies that are fighting – we have to convince them that we are not their enemy, to grant us access to reach the people living in these areas.

13:26 – 13:49 If the warring parties believe that we will expose them before an international judicial body, we will never be able to reach the victims or do our job. Therefore, we don’t have a hand in this. We do not provide the International Criminal Court with information and we do not deal with it. We said so to the Sudanese government and shared it publicly.

13:49 -14:15 Presenter BREAK

Mr. Thierry Durand, Operations Director at Doctors Without Borders, we will return to questions and answers after this break, Ladies and gentlemen, we will be back after this short break

14:16 – 14:31 Presenter: What do you think of the accusations of President Omar al-Bashir, who described you in public rallies as spies, and that you are colluding against Sudan for the benefit of some governments? What do you think of these accusations?

14:32 – 14:55 There are organizations that are indiscreetly fighting for this, and they might have given information to the ICC in some way. The ICC might have also used non-confidential reports published by MSF to describe the situation, especially those of 2003.

14:56 – 15:14 However, I think that they have the wrong target. Human rights bodies that are not present in the field are the most active in such contexts, particularly Save Darfur and Darfur emergencies that work with lobbyists or have political links.

15:15 – 15:24 However, MSF doesn’t have a hand in this. The accusation pointed at MSF are wrongful and exaggerated. This discourse is not new on the part of the Sudanese president.

15:25 – 15:31 For several years, he considered foreigners as enemies, and we can say that we are not even a French organization.

15:32 – 15:43 We can consider the message related to the presence of MSF in Sudan is addressed to the French government, while our relationship with the French government is completely non-existent.

15:44 – 15:53 We don’t have a good relationship with Mr. Kouchner, who left MSF thirty years ago to devote himself to well-known political work.

15:54 – 16:04 Our relationship with them is very bad. We do not receive or even ask for a penny from the French government. The Sudanese government is aiming at the wrong target.

16:05 – 16:23 We are an international movement, and we have Sudanese working with us in Chad, DRC, and Kenya. There are efficient Sudanese doctors working in Yemen. We also have Japanese and Ivorian working with us. No one can say that we are a French organization.

16:27 – 17:02 Presenter: There is staff from MSF who are still in Sudan. They are Sudanese. What is their situation right now? Are you worried about them? Are you afraid that they might face harassment following the accusations made to the organization and its staff, describing them as spies colluding with other organizations that are hostile to the Khartoum government?

17:03 – 17:27 Thierry Durand: They’re worried, I’m worried. The government informed us through a humanitarian committee that there is no need to worry. But they are all afraid, afraid of… They already lost their jobs. For MSF, more than 1,000 people are in this situation right now.

17:28 – 17:40 When we talk about the Sudanization of humanitarian assistance, you know? - The two sections Dutch and French were expelled. There were 40 international staff and 1,000 Sudanese members.

17:41 – 17:57 Sudanization is strong to a great extent. Sudanese are the ones working with MSF and they have lost their jobs. They are now afraid that no opportunity would arise for them, especially with the government. They worry that their names would be on the blacklist.

17:58 – 18:12 When they get to their homes at night, their families accuse them of working with the spies. They would feel embarrassed, and we would too because of what they are going through.

18:13 – 18:32 This has gone on for longer than it should have. When he attacked us, the president also attacked our Sudanese colleagues. There are more than 6500 Sudanese working with the expelled organization. The situation is unpleasant.

18:34 – 18:53 Presenter: Recently, some workers from the humanitarian organization have been kidnapped. Who kidnapped them? Was the operation planned to cause more harm to the Sudanese government, as some may say?

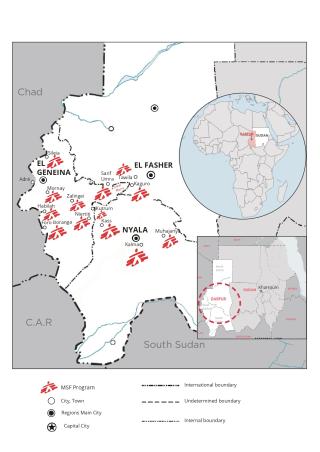

18:54 – 19:24 Thierry Durand: I don't know, I can't say that. It's clear that the president -- When he goes to El Fasher or Nyala, and when he vents in front of mass audiences, saying that the organizations are thieves and spies, some armed bandits might seize the opportunity. They consider us spies and thieves, then the armed bandits can do whatever they want. Maybe this is what’s really going on.

19:25 – 19:37 Regarding hostage-taking, the government is the one who settled the case, it is the one that met the young men and was able to release the hostages without violence.

19:38 – 19:48 This is good, but it is also worrisome since it can be repeated everywhere, I was personally attacked in Darfur by thieves.

19:49 – 20:03 Fortunately, I was with Sudanese friends - sheiks and the mayor of El Geneina- and no harm was done, but we faced other serious problems, very serious, including road attacks.

20:04 – 20:22 The intended message in these situations worries us a lot, especially when thinking about the future. I do not know if the MSF teams that were not expelled or other humanitarian organizations can keep operating in Sudan in such circumstances.

20:23 – 20:37 We don't know who is behind all of this. There were some small claims. MSF was asked to request the ICC to withdraw the indictment.

20:38 – 20:40 Then there was a ransom case and after that, the hostages were released.

20:42 – 21:10 Presenter: Mr. Thierry, President Omar Al-Bashir announced it openly. He decided to abandon international humanitarian organizations and rely on Sudanese humanitarian organizations, or what he called the “Sudanization of humanitarian work.” Do you think that Sudan has the capabilities, material, and human resources to support the people in need?

21:11 – 21:26 Thierry Durand: We have no objection to that. As I told you a while ago, aid in general has been Sudanized to a large extent. 98% of our workers are from Sudan.

21:27 – 21:34 There is an issue related to resources. You can’t assign a couple of persons and tell them to work in Darfur.

21:35 – 21:44 There is an integrated system behind our work that is based on logistical support, supply, finance, strategies, experience, and competencies.

21:45 – 21:54 There are several good Sudanese organizations. Red Crescent societies, in the Arab world, might have the potential to achieve this goal.

21:55 – 22:05 There are the Emirates Red Crescent and the Jordanian Red Crescent that are efficient actors and are able to provide quality assistance.

22:06 – 22:19 One of the biggest problems will be related to the independence of these organizations since the situation in Darfur, as I told you, is extremely polarized and politicized even within the camp.

22:20 -22:29 Problems have occurred before on several occasions. Refugees are angry at the government because of the situation they’ve been going through for five years.

22:30 – 22:45 When we say that the organizations are biased or non-neutral, or that they represent the government, they reprimand those organizations. I think that it will not be easy at all.

22:46 – 23:05 I think that governmental organizations know that well. I don’t think that they all have sufficient capabilities to do what is required, there are some Sudanese NGOs whose independence will be revisited in the near future by the people of Darfur themselves.

23:07 – 23:27 Presenter: Do you plan on returning to Sudan? Are you in contact with the Sudanese government in order to return? Do you want to resume working in Sudan or are the operations over, and there is no way to return to Sudan?

23:28 – 23:37 Thierry Durand: I know Sudan and the Sudanese very well. The doors will never be closed completely.

23:38 – 23:48 The doors are always open for discussion. We would like to keep these doors open and continue these discussions.

23:49 – 24:01 I think the situation is very difficult and very tense at the moment. There is a lot of emotionality and anger, and harsh words are being uttered.

24:02 – 24:24 For us, as you know, Sudan is also a story of love and diverse friendship that arose thirty years ago in difficult circumstances. Some of the volunteers died in Sudan. We have many Sudanese friends, and we hope to return, but it maybe won’t happen in the near future.

24:25 – 24:36 But we will do everything in our power to continue discussing with the Sudanese authorities and we would like to meet authorities at senior levels, and so far, we do not have contact with people working at senior levels.

24:37 – 24:45 They are preliminary discussions, and these discussions will probably take time. I think it takes some time.

24:46 – 25:01 There are other issues. The issue of independent humanitarian and relief workers such as MSF, must be isolated from the rest of the issues, the political issues and the ones related to the debate between Sudan and the international community.

25:02 – 25:11 Sudan has many friends in the African Union and in the Arab League, etc., and I believe that it can rely on them.

25:12 – 25:31 It is hoped that this international, private, political and judicial problem will find a satisfactory solution, but we must be isolated from all of this, so the government should not involve us. We do not have any authority to pressure any member states into voting in any direction.

25:32 – end Presenter: Mr. Thierry Durand, MSF Operations Director, thank you very much for this interview. And thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for staying with us until the end. We hope to meet you soon. This is Noureddine Bouziane greeting you from Paris. Goodbye.